VERNAL BRANCH REMEMBERS the official instructions from her first civil rights protest: “Stay polite, and stand your ground.” It was the summer of 1962 in Winston-Salem, N.C., where Branch and her family had lived for generations under harsh segregation laws, and where organized nonviolent protests continued after the famous 1960 sit-ins at the Woolworth lunch counter 30 miles down the road in Greensboro.

Barely out of childhood and the only girl in a family of three children, she was forbidden by her father from participating in the protests. She would slip out of the house and go anyway. “I guess you could say I was a maverick at 12,” says Branch, now 63, with a laugh, from her home in Richmond, Va.

She never got arrested during the protests. But young Vernal threw her heart into the cause, singing and marching with blacks and whites alike outside the cafeterias that refused to serve her. And, in an act that encapsulated both the civility and determination of the protesters, she’d wait in line outside the cafeteria for her turn to confront the guards at the entrance. “When I got to the door, I’d say, ‘I want to be seated at the lunch counter,’ and they would turn me away,” she says. “Then I’d go to the back of the line and start again. We did that all day long, day after day.”

Polite but firm: Great advice not only for civil rights protesters ushering in sweeping reforms during the tumultuous 1960s, but also for a cancer activist like Branch, working more quietly but no less determinedly in the new millennium. Although she now boasts a long resume of accomplishments in the politics of cancer activism, with an impressive Rolodex of contacts to match, it wasn’t until her cancer diagnosis at age 45 that Branch, now the public policy manager at the Virginia Breast Cancer Foundation, rediscovered her inner activist. The cancer had made her feel vulnerable and scared for the first time in her life.

Standing Strong: Vernal Branch’s activism was on display at a June meeting of the Cancer Action Coalition of Virginia. Photo by Dan Chung

Branch had recently moved to Southern California in 1995 when she noticed swelling and warmth in her left breast. Her doctor couldn’t feel anything, though, and a mammogram and an ultrasound similarly came up negative. But then two months later, Branch felt in her breast a lump the size of a pea, and three weeks later it was the size of a golf ball. Her doctor immediately scheduled another ultrasound and finally found the fast-growing tumor. A couple of days later, following a biopsy, Branch learned that she had hormone-sensitive stage I breast cancer. She underwent a single mastectomy, followed by immediate reconstruction, and also began treatment with tamoxifen. She spent six months recovering from the surgeries and a subsequent infection complication—but started her activism a mere eight weeks after diagnosis.

For that first foray, Branch teamed up with a colleague of her husband’s who had also recently been diagnosed with breast cancer. They hosted a fashion show and silent auction at a clothing boutique and restaurant near Branch’s home in Carlsbad, Calif. Proceeds went to a local chapter of the now-defunct Y-Me National Breast Cancer Organization. Before long, Branch was volunteering on a regular basis with Y-Me.

A year after her cancer surgery, she attended her first National Lobby Day in Washington, D.C., hosted by the National Breast Cancer Coalition (NBCC). The event involved up to 1,000 people rallying in front of the U.S. Capitol, attending workshops on cancer advocacy, and visiting legislators to discuss breast cancer. “It was the most exhilarating thing I’d ever been involved in,” Branch says.

Getting involved appears to come naturally to her. “Activism must be in my DNA,” says Branch. Her mother’s mother, in a remarkable act of courage for an African-American woman in the South in the 1940s, tried to organize a labor union in the R. J. Reynolds tobacco plant where she worked in Winston-Salem—and got herself and her husband fired in the process. Branch’s mother, born just two years after women won the right to vote, registered members of the Winston-Salem black community to vote and then brought them to their polling places, defying the widespread voter intimidation present in the South in the 1950s.

On the other side of the family, Branch’s paternal grandfather, a janitor who was self-educated, co-founded the Winston Mutual Life Insurance Company in 1906. He later went on to become its president. For years, it was the only health and life insurance company in the area offering policies to African-Americans, and eventually Winston Mutual Life Insurance became one of the largest black-owned businesses in North Carolina. Branch’s father also worked at the firm. “It was more than just an insurance company,” Branch says. It also represented security and stability to people who were routinely denied such basics based solely on their skin color.

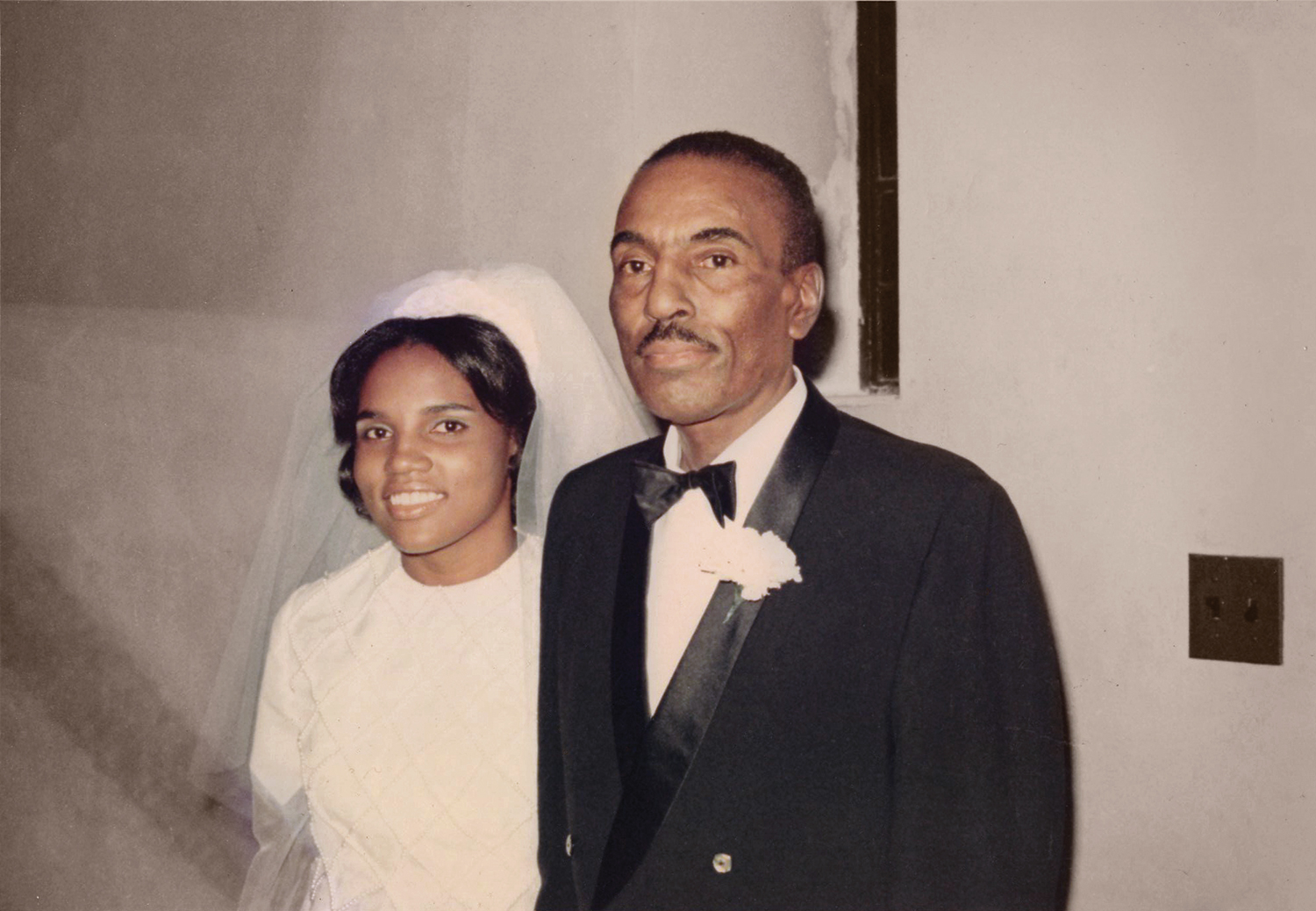

Standing Strong: Family has long proved a motivating force for Vernal Branch, shown here with her father, Leander Hill, at her 1971 wedding. Photo Courtesy of Vernal Branch

It was a sad twist of irony, then, when nearly a century later Branch was herself denied health insurance coverage for reasons beyond her control: her breast cancer diagnosis five years earlier. For three uninsured years, she and her family lived in fear that her cancer would return, knowing that they would be unable to afford the out-of-pocket costs for treatment if it did. Her story was so compelling that the White House asked her to speak about it twice: with first lady Michelle Obama and other dignitaries at a breast cancer awareness event in 2009 in the Rose Garden, and again in 2011 in front of the House of Representatives Democratic Steering and Policy Committee during a hearing on Republican efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

Branch is indeed a compelling communicator, whether before an audience or one-on-one. She has a public speaker’s knack for well-cadenced sentences, her voice calm, soothing and authoritative. Always impeccably attired in elegant textures (she started college in 1968 at North Carolina Central University as a textiles design major, before later switching to history), with close-cropped hair and a preternaturally smooth face, she has the appearance—and energy—of a woman many years younger than her age.

Her youthful vitality is obvious to others in the cancer community. “I went to [the 2009 National] Lobby Day and saw her work,” says Carla Finkielstein, a cancer molecular biology professor at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, who regularly invites Branch to speak to her students and fellow faculty. “When I left, I realized I couldn’t do a tenth of what she does.” Finkielstein was so inspired by Branch’s work that she now serves on the board of the Virginia Breast Cancer Foundation, where Branch devotes her time to working on national and state policy issues concerning cancer.

One of these issues was President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, and Branch’s job was to help persuade senators and representatives to vote for this controversial legislation. “She’s very strong and very driven, and at the same time very polite, centered and focused,” says Finkielstein. “She understands the problem and tries to change things, but is very patient with the system. Her persistence is unbelievable. She knows the message that she wants to leave in that office. She knows in advance that legislators are not going to like it, but she goes anyway. And then over the years, she’s able to get them to switch sides.”

Branch doesn’t talk much about her early civil rights experiences, but fellow activists aren’t surprised to hear of it. “That sounds just like her,” says breast cancer survivor Vicky Carr, an activist with the nonprofit After Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Branch’s mentee. “She’s got a lot of grit. … If Vernal Branch makes a recommendation, people listen. At first I was really intimidated by her—she commands such respect. But I saw her heart and passion and how eager she was to help others.”

Branch’s action-packed activism schedule would make a lesser human weep. In the past 13 years she’s been a member of the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program, a national recruiter for the National Institute of Environmental Health Sister Study, a member of the National Cancer Institute Director’s Consumer Liaison Group, a member of the external advisory board for the Duke Cancer Institute, a member of the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board and a scientific advocate with the University of Virginia, the Duke Cancer Institute and the California Breast Cancer Research Program. She has also been a participant in multiple science education programs for cancer patient advocates, including the NBCC’s Project Lead and the American Association for Cancer Research’s Scientist↔Survivor Program.

Standing Strong: Vernal Branch with her husband, Calvin. Photo by Dan Chung

But Branch is used to being on the go. She and her husband, Calvin, have lived in 13 cities during their 42 years of marriage, moving for his corporate positions at Procter & Gamble and other companies. She’s a savvy traveler, known to take a red-eye flight back to the East Coast from California, change clothes and freshen up in the airport restroom, then catch a ride straight to a meeting or speaking engagement. There’s no time for excuses. “When I say I will be there,” she says, “I need to be there.”

Competitive athletics would probably have suited Branch, if that had been common for women to pursue in the 1960s. She was an avid tennis player until the mastectomy robbed her of her muscular strength. Now she works out every morning on the elliptical machine in the gym of her modern condo building, where she and her husband have a sweeping view from their home of historical downtown Richmond.

Instead, her sons became the athletes, two of them professionally. Calvin Jr., now 39, played pro football for the Oakland Raiders for seven years and is now a scout for the team, while Colin, 33, played first for Stanford University and then the Carolina Panthers. The middle son, Christopher, 37, left the pro sports to his brothers and is a restaurant manager in California. The sons, teenagers when Branch was diagnosed with cancer and who banded together to take care of her during recovery, have given Branch the ultimate gift: six grandchildren, ages 2 to 14, whose photos line the walls and shelves of her home.

Vernal Branch attends a 1999 breast cancer rally in Sacramento, Calif. Photo courtesy of Vernal Branch

Sage, now 8, was Branch’s first granddaughter, and her birth turned up the dial on Branch’s activism convictions, says Sage’s father, Colin. “When Sage was born, my mom had more passion than ever before, because she knew what my daughter might have to go through with breast cancer,” he says. Sage, as friendly and assertive as her grandmother, knows that her “nana” gets to help people by going to the nation’s capital each year. “Both Sage and my mom are hammering at me to let Sage go up for Lobby Day,” Colin says with a laugh.

In fact, it was this still-hypothetical granddaughter, along with a strong sense of family, history and community, that inspired Branch during her breast cancer treatment and which continue to propel her activism. “I didn’t realize it at the time of my diagnosis, but breast cancer runs in my family,” she says. “I thought, ‘There’s another generation of women coming behind me. I want to be able to say in my lifetime that we have made a difference in breast cancer.’ Activism took the focus off me and got me thinking about the bigger issue, about how this affects a lot of people across the country. I grew up in the civil rights era, the age of giving back. We always helped people in our community. We made a difference.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.