STEPHEN ESTRADA was a 28-year-old trying to launch a career as a hairstylist when he was diagnosed with stage IV colorectal cancer in 2014. He also learned he had Lynch syndrome, a hereditary condition that increases cancer risk and affects 3 to 5 percent of colorectal cancer patients, but his doctor said this wouldn’t affect his course of treatment. Estrada, who lives in Denver, had chemotherapy and NanoKnife treatment, a procedure meant to kill cancer cells with electrical current. But his cancer kept growing.

Estrada decided to change his care from a community oncology practice where his doctor treated patients with a variety of cancer types to the University of Colorado Cancer Center in Aurora, an academic medical center where his oncologist would be focused just on gastrointestinal cancers. His new oncologist told him that his Lynch syndrome meant his tumor was microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H), placing him among the small group of colorectal cancer patients who are candidates for immunotherapy due to their tumor characteristics.

About a year into his diagnosis, Estrada enrolled in a phase I clinical trial of the immune checkpoint inhibitor atezolizumab, later approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as Tecentriq, and Avastin (bevacizumab), a therapy meant to work by preventing blood vessels from growing to feed tumors. “I could tell that my life was turning around” very early in the trial, Estrada says. “My body was returning back to me.” Today Estrada shows no evidence of disease, and he is still participating in the trial.

Estrada hadn’t even heard of tumor biomarkers when he was diagnosed with cancer, but today he knows he is one of the small but growing number of patients who have benefited from molecular biomarker-driven therapies—treatments directed by the genomic characteristics of a patient’s cancer.

Estrada got treatment with an experimental therapy on a clinical trial after connecting with a particularly knowledgeable doctor. Immunotherapy drugs have since been approved for certain patients with metastatic colorectal cancer like Estrada’s that is MSI-H or that tests positive for DNA mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR). There are now treatments approved by the FDA based on cancer biomarkers for patients with more than a dozen specific cancer types. And the FDA has approved two drugs, Keytruda (pembrolizumab) and Vitrakvi (larotrectinib), for patients with any advanced solid tumor type regardless of tissue of origin, provided their cancers have certain molecular characteristics.

Despite the growing number of therapies available, therapy guided by biomarkers is not equally accessible to everyone. Data show disparities both in who gets their cancer tested for biomarkers in the first place and who is treated with corresponding therapies.

Estrada is now a certified patient navigator working for the Colorectal Cancer Alliance as the senior coordinator of community engagement, a job that includes staffing their patient helpline and moderating their online community. He is also a member of the organization’s Patient and Family Support team. Estrada encourages patients to have conversations with their doctors about biomarker testing and is helping to develop an education campaign on biomarkers. “Most patients don’t have an idea of what a biomarker is, what it implicates and what it even means for them at all,” he says.

Some mutations are inherited, while others are found only in a patient’s cancer cells.

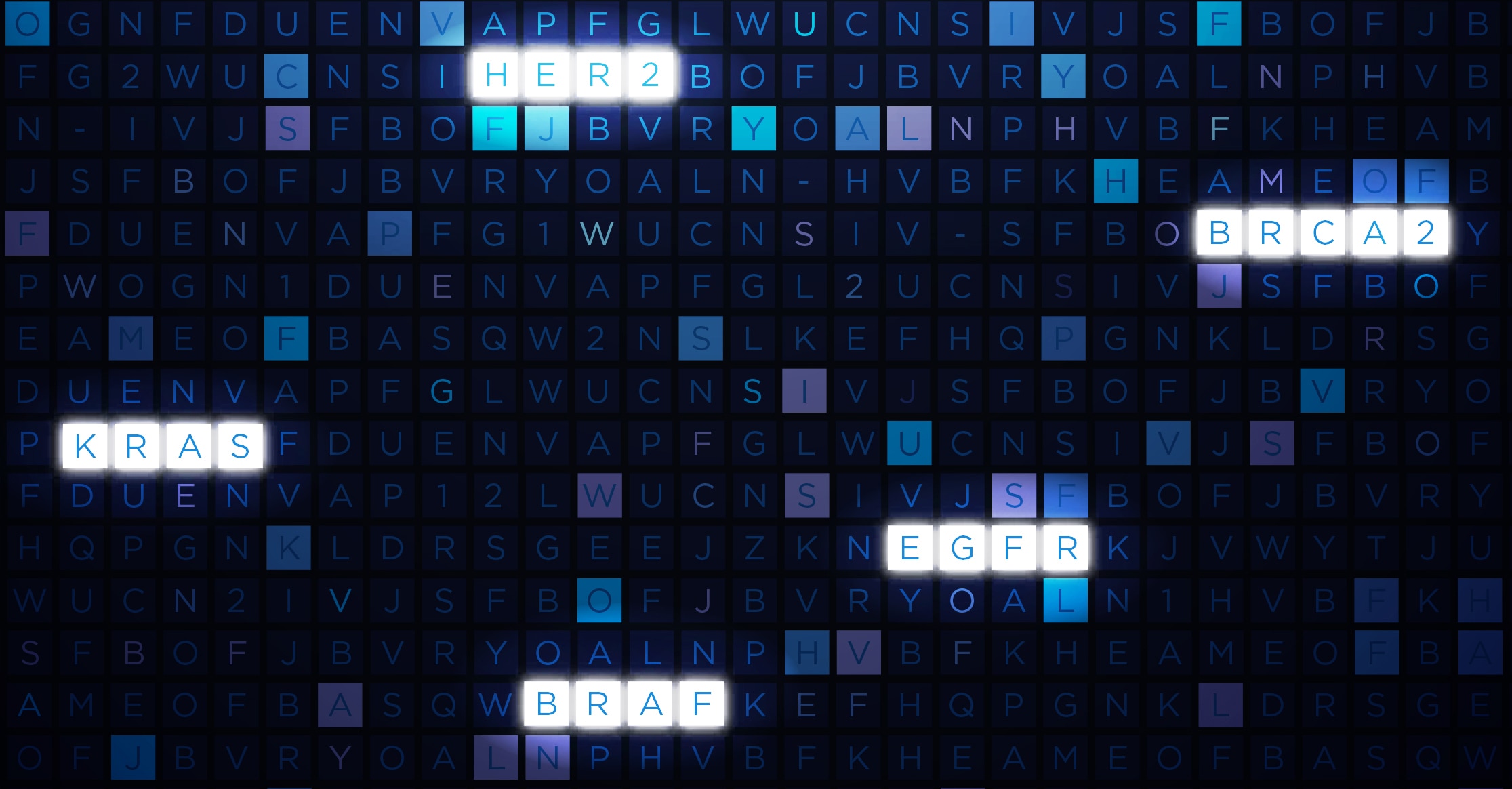

Most mutations that guide treatment with targeted therapies are not hereditary. Instead, mutations in genes like ALK, BRAF, EGFR and KRAS usually first happen in a patient’s cancer cells. The rest of the patient’s cells will not have the mutations, and the patient will not pass the mutations on to his or her children.

There are some exceptions. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are often passed from generation to generation, for example. Hereditary mutations are present in both a patient’s cancer cells and in the rest of the cells in their body. Researchers have known for many years that hereditary BRCA mutations increase cancer risk, but they are now learning that patients who have these mutations are more likely to benefit from a class of targeted therapies called PARP inhibitors than patients without these mutations.

Researchers have also recently learned that patients with Lynch syndrome—a hereditary disorder that increases the risk of colorectal, endometrial and other cancers—have an increased likelihood of benefiting from immunotherapy drugs. The tumors of people with Lynch syndrome usually have a pattern of DNA damage referred to as high microsatellite instability (MSI-H). Some other people have MSI-H tumors but do not have Lynch syndrome, and they also have an increased likelihood of benefiting from immunotherapy.

Heather Hampel, a cancer genetic counselor at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, says she hopes that interest in being tested for MSI status to guide treatment will also lead more people to find out whether they have Lynch syndrome. Patients who know they have Lynch syndrome and their families can undergo extra screening and preventive surgery. Hampel says that patients who learn their tumors are MSI-H should make sure to get follow-up testing to see if their mutations are hereditary or not, as an estimated 16 percent of patients with MSI-H tumors have Lynch syndrome.

Discovering Disparities

There are disparities in access to even the oldest targeted therapies, according to Katherine Reeder-Hayes, a medical oncologist specializing in breast cancer at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Tamoxifen was first approved in 1977 to treat patients with breast cancer by blocking hormone receptors that are present in 83 percent of breast cancers. Reeder-Hayes’ research indicates that black women are significantly less likely than white women to receive appropriate hormonal therapy for their cancer, even though women with breast cancer today routinely have their tumors tested for hormone-receptor status regardless of race.

Herceptin (trastuzumab), which targets breast cancer cells making large amounts of the HER2 protein, was first approved for treatment of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer in 1998 and for early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer in 2006. Around 17 percent of breast cancers are HER2-positive. In a paper published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in April 2016, Reeder-Hayes and her colleagues found that 50 percent of white women on Medicare with nonmetastatic HER2-positive cancer diagnosed in 2010 or 2011 received Herceptin, compared to 40 percent of black women. In women with HER2-positive stage III cancer—a group that stands to particularly benefit from Herceptin—74 percent of white women received the drug, while just 56 percent of black women did.

Reeder-Hayes says the experience of breast cancer patients should prompt researchers to be on the lookout for disparities in access to precision medicine as new therapies arise for other cancer types. In breast cancer, “we know that the largest disparities tend to exist where treatments are new, where they are complex and where they are costly,” she says.

Missing Targets

Advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the solid tumor type that comes with the highest number of recommended tumor mutation tests. Today, mutations in four genes—ALK, EGFR, ROS1 and BRAF—guide treatment with therapies approved by the FDA specifically for advanced NSCLC patients with those tumor biomarkers.

Clinical practice guidelines—recommendations that influence what treatment choices physicians make—often go beyond just recommending testing for biomarkers the FDA has mentioned in drug indications. For advanced NSCLC, for instance, the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that testing be done as part of broader molecular profiling to look for emerging biomarkers.

“It’s great that we’re doing all this genetic testing, but is that really getting out to communities?” asks Christopher Lathan, a medical oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston who studies disparities in lung cancer care. EGFR and ALK testing, for instance, has “been around for long enough that you should really see diffusion into regular communities at a really high rate. Some of the more recent papers are saying that’s not the case,” he says.

A paper published in March 2018 in BMC Cancer looked at data on tumor testing for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries diagnosed with lung cancer between 2011 and 2013. The researchers found that patients living in ZIP codes near National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers—academic centers recognized for their research—were more likely to receive molecular testing of their tumors than those living farther away. Hispanic and black patients and Medicaid recipients were less likely to get testing than average, while Asian and Pacific Islander patients were more likely to get testing.

A study published in October 2018 in JCO Precision Oncology focused on testing for ALK mutations in community oncology practices—oncology practices that are not affiliated with an academic institution. In 2011, 32 percent of patients with advanced NSCLC were tested for ALK mutations. By 2016, 62 percent of these patients were tested. Patients who had Medicaid were 40 percent less likely to get tested than those with private health insurance.

Time is also critical for patients with metastatic lung cancer. Nathan Pennell, a thoracic oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, says that he sometimes has tumor testing results the first time he meets with a patient, because they are ordered automatically as soon as a pathologist makes a diagnosis of non-squamous NSCLC. But at other locations, patients may not have testing ordered until they’ve met with their oncologist.

Research indicates that, as in lung cancer, geographic location and insurance status influence whether colorectal cancer patients get tumor biomarker testing. In 2009, KRAS testing was recommended by NCCN guidelines for all metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Patients who test negative for KRAS mutations are candidates for treatment with an EGFR inhibitor. By 2013, however, just 35 percent of patients diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer were receiving KRAS testing, according to a study published in December 2017 in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Patients were more likely to get testing if they lived in a metropolitan area than if they lived in a rural area and if they had Medicare or private insurance as opposed to Medicaid or no insurance.

“When it comes to local cancer clinics and people that are being treated in rural areas, the chances [of their tumor being tested] are lower,” says Sharyn Worrall, the patient education manager at the nonprofit organization Fight Colorectal Cancer, which provides patients with information on tumor biomarkers through its Biomarked campaign. Worrall says that beyond lack of awareness about testing, fear of the personal financial burden can also keep patients from getting tested.

Experts see a trend toward increased insurance coverage for genomic testing.

Insurers generally pay for tests that assess single molecular biomarkers in cancer cells when clinical guidelines recommend testing for these biomarkers. But insurers have been more reluctant to pay for tests that use next-generation sequencing (NGS) to give patients information on hundreds of genes.

Many mutations that turn up on broad sequencing reports will not guide treatment with therapies approved for that patient’s cancer by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The reports can suggest off-label treatments—drugs approved for another cancer type that may or may not work in a patient’s own cancer type. And they can tell patients what sorts of clinical trials they might want to look for.

In March 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that Medicare would cover NGS tests approved or cleared by the FDA for patients with advanced cancer, paving the way for increased coverage of broad tumor sequencing at least for patients on Medicare.

It isn’t known yet whether private payers will follow Medicare’s example, says Julia Trosman, who studies reimbursement for precision medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. “I think we’re seeing a gradual trend towards more coverage,” she says. “It varies across payers.”

For now, Trosman says, NGS is likely paid for by a variety of sources, including insurance but also other payers. Some patients at large academic centers will get NGS as part of research initiatives paid for by grants and other institutional funds. In other cases, a cancer center might charge a patient’s insurance but then find internal charity funds to pay for testing if the claim is denied. Some testing companies offer financial assistance funds to cover bills or portions of bills that insurance denies. In other cases, patients end up paying for testing out of their own pockets—though there’s little data on how commonly this occurs.

Testing Across Cancers

In May 2017, the FDA approved Keytruda for any advanced MSI-H or dMMR solid tumor type in patients without other satisfactory treatment options—making tumor testing relevant to a much broader group of patients. It was the first time the FDA had approved a therapy without regard to where the tumor originated, called a tissue-agnostic approval.

The FDA issued its second tissue-agnostic approval, for Vitrakvi, in November 2018. Vitrakvi is approved for patients with advanced solid tumors whose cancers have certain mutations involving any of the three NTRK genes and who lack other satisfactory treatment options or whose cancers have progressed following treatment.

David Hyman, a gynecologic medical oncologist and chief of the Early Drug Development Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, says we’re now at a stage where performing “a single genetic test at some point in the treatment of any patient with advanced cancer” should be strongly considered. Hyman, who co-authored a study on the efficacy of Vitrakvi in the New England Journal of Medicine in February 2018, says that he would advocate for patients to receive one test that can detect both types of alterations that now guide tissue-agnostic treatment.

At the same time, it is important to have realistic expectations about the likelihood of benefit from tumor testing, says Hyman. The rate of MSI-H disease is 15 percent in colorectal cancer and up to 30 percent in endometrial cancer, but across solid tumor types the rate is under 4 percent. Meanwhile, NTRK fusions are found in up to 1 percent of solid tumors.

Still, the benefits of Vitrakvi and Keytruda for some patients are significant enough to justify testing, Hyman says. “If we don’t test everyone, we’re really going to miss the opportunity to give this dramatically life-altering therapy to some of these patients,” he says.

Karen Pratte Kiernan of Naperville, Illinois, was diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer in March 2017 at age 60. She only learned her MSI status after her older sister urged her to get testing through Know Your Tumor, a program of the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN). For patients participating in the program, PanCAN pays for a third-party company to coordinate testing. Billing for the tests themselves is handled through patients’ health insurance.

Kiernan, a retired high school nurse, was diagnosed months before the approval of Keytruda for MSI-H solid tumors. She learned in February 2018 that she was among less than 2 percent of pancreatic cancer patients who have tumors that are MSI-H, and she started on Keytruda in April 2018.

“I’m a different person,” Kiernan says of her life now. Her tumors have gotten smaller. She had been suffering from severe back pain, but a week after she started the drug, the pain went away. She even got a new dog, Lucy, an emotional support animal, and she is arranging to volunteer with her as a therapy dog at cancer centers.

Kiernan says that without her sister’s prodding, she would never have been able to benefit from Keytruda. She even remembers bringing her original oncologist a newspaper article on immunotherapy and being told that it wouldn’t work for her because she had pancreatic cancer.

“My sister is a reader. She just surfs the whole internet,” Kiernan says of her path to tumor testing. “She’s older. She’s retired, has the time and loves me very much. She did homework and found out.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.