CHRISTY LEONARD HAND TO LEARN FAST in the weeks after her husband, Tony, was diagnosed with stage IIIC stomach cancer at age 39 in 2012. The Fayetteville, North Carolina, resident learned to give Tony injections to prevent blood clotting and to operate a feeding tube following surgery. During his chemotherapy and radiation treatments, she juggled her information technology job with caring for Tony and their four children—they have five—still living at home. She had no time to reflect on her role.

“I didn’t even know what a caregiver was,” Leonard, now 36 years old, recalled during a panel discussion at a National Institute of Nursing Research caregiving conference in August 2017. “I showed up at an event and they said, ‘Oh, you’re his caregiver.’ I said, ‘Sure.’”

About 39.8 million people in the U.S. provide unpaid care for adults annually. Of these, at least 2.8 million care for people whose primary problem is cancer, according to the 2016 report Cancer Caregiving in the U.S., produced by the National Alliance for Caregiving. But caregivers’ needs are often overlooked by health care professionals, policy makers and even caregivers themselves, who tend to neglect their own psychological and medical care.

“Caregivers don’t get much recognition for what they do,” says Jaymari Jones of Kannapolis, North Carolina, whose husband, Solomon, was diagnosed with stage IV colorectal cancer in 2015. “Caregivers are there when nobody else is there in the middle of the night when your loved one is sick and can’t get out of the bed. … You have to dig deep down in your heart and pull some stuff out you didn’t know you had. It’s not like a nurse. You don’t get paid to be a caregiver. It’s not like you can just go to work, clock in and out and leave.”

Caregiving responsibilities can include familiar chores like cooking dinner, paying bills or cleaning the house. They can also be difficult physical tasks like helping a loved one get in and out of bed and complex medical tasks like giving injections, changing the dressing on surgical wounds, or cleaning and maintaining the sites of catheters or colostomies. Caregiving can take a toll on finances and make it difficult for caregivers to keep a job, and caregivers have high rates of depression and anxiety.

“We need to really think of better ways to support family caregivers,” says Betty Ferrell, director of the Division of Nursing Research and Education at City of Hope in Duarte, California. “Family caregivers are pretty invisible in the health care system.”

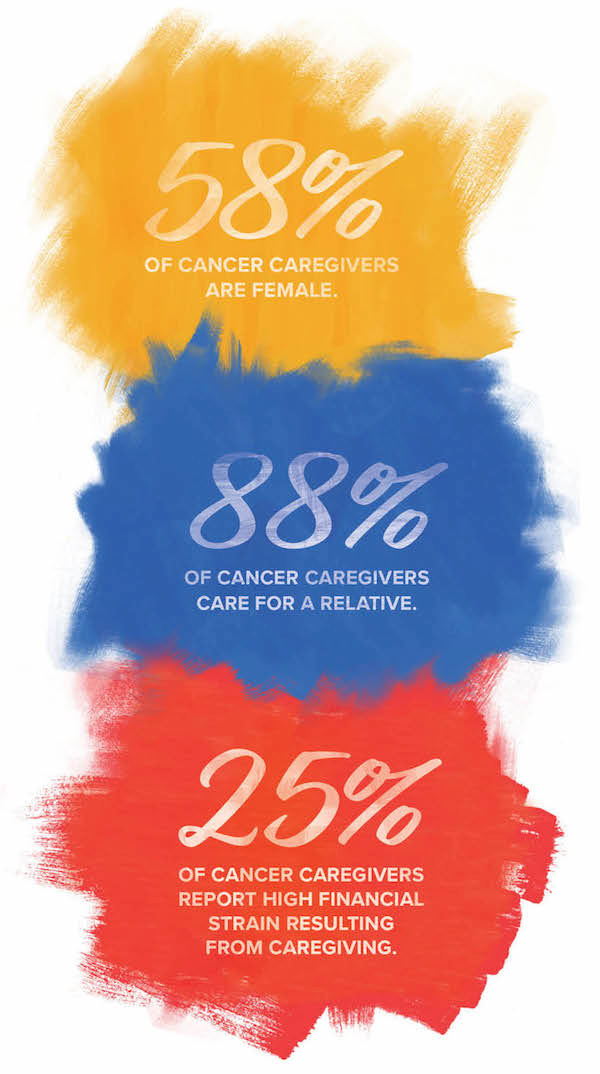

Statistic from Cancer Caregiving in the U.S.

The Outpatient Shift

When Ferrell started her career as a nurse 40 years ago, in 1977, “the inpatient hospital was the center of cancer care,” she says. When patients’ pain ramped up or when their families became exhausted, patients went to the hospital for long stays.

In the 1980s, new reimbursement incentives began to encourage hospitals to shorten inpatient stays. Ferrell recalls thinking, “We’re not doing such a great job even here in the hospital, with a pharmacy down the hall and nurses and physicians, of taking care of these cancer patients and their families. How in the heck do we think that families are going to do this at home in their own living rooms?”

The decline in the length of hospital stays for cancer patients has been striking. In 1965, the year of the first National Hospital Discharge Survey, cancer patients who were admitted to U.S. hospitals stayed an average of 14.8 days. By 2010, the final year of the survey, hospital stays for cancer patients in the U.S. lasted 6.3 days on average.

Taking on tasks like caring for wounds, operating specialized medical equipment like feeding tubes and helping patients with large numbers of prescriptions, including injections, is now the norm for caregivers, says Susan Reinhard, senior vice president and director of the AARP Public Policy Institute and co-author of Home Alone, a 2012 report on the complex tasks that caregivers undertake. Caregiving for cancer patients may be even more complex than for those with other health conditions. Cancer Caregiving in the U.S. reported that 72 percent of cancer caregivers undertake medical/nursing tasks, compared to 56 percent of caregivers for patients with other conditions. The report found that 43 percent of cancer caregivers say they perform medical/nursing tasks and did not receive any training.

Since 2014, 39 states have passed the Caregiver Advise, Record and Enable (CARE) Act. This legislation, developed by AARP, requires hospitals to ask patients if they’d like to have hospital staff include the name of a caregiver in their records, notify that person when the patient is going to be discharged or moved, and provide training to the caregiver on what to do to help the patient at home.

Even if they do receive instruction, caregivers report that they don’t always remember the details. “There’s a lot of information we’re giving to patients and their families, but they are often so overwhelmed and full of anxiety and uncertainty and stress that it’s difficult to know whether or not they are being adequately trained or prepared,” says oncology nurse and researcher Michelle Mollica, a program director at the National Cancer Institute in Rockville, Maryland.

“It’s not fun being at the hospital,” recalls Renata Louwers, whose first husband, Ahmad Khoshroo, was diagnosed with early-stage bladder cancer at age 69 in 2011 and with stage IV bladder cancer in 2013; he died in 2014. “You usually want to get out of there as fast as possible … but we were sort of scared to go home because we didn’t know what to do.”

Technical tasks are challenging, but so is decision making, says Louwers, who lived in San Francisco at the time. Her husband was prescribed opioids for pain, but the medications that controlled his pain one day were not always effective the next. Louwers worked with his doctors to try different medications, readjust timing and dosage, and manage side effects like constipation and grogginess. To keep track of his ever-changing constellation of medications, Louwers says, she wrote them down on a whiteboard. “I felt like I was running a hospital.”

Statistics from Cancer Caregiving in the U.S.

The Cost of Caregiving

Unpaid caregivers in the U.S. provided services worth $470 billion in 2013, according to AARP. But despite apparent savings for the health care system, caregiving responsibilities can place considerable financial stress on families.

Around half of cancer caregivers have jobs while caregiving, according to Cancer Caregiving in the U.S. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) requires that employers with 50 or more workers allow caregivers to take off work for up to 12 weeks annually without pay to care for a parent, spouse or child. Four states—California, New Jersey, Rhode Island and New York—have passed laws enacting paid family leave programs funded through payroll taxes that allow caregivers to receive part of their usual salary while on leave.

Leonard says that working from home and having a compassionate and flexible boss and team have allowed her to maintain her career. Other caregivers may have to cut down their hours on the job, take unpaid leave or quit their jobs. That can cause financial stress, especially when the patient is also unable to work and medical costs are mounting.

When Jones learned in March 2015 that her husband, Solomon, then age 36, had colorectal cancer, she had been working at the same company for nearly four years. She took personal leave and unpaid family leave intermittently to care for him. Solomon finished active treatment in February 2016 and was told he was in remission, but he continued to suffer from pain and radiation-related side effects. The couple had been receiving subsidized day care for their children—who are now ages 8, 5 and 4—through a state program for families in crisis. But once Solomon was not in active treatment, they were no longer eligible.

Around the same time, Jones learned that she had taken too much time off in 2015 to qualify for further unpaid leave under the FMLA. Concerned that Solomon was too ill to care for the children on his own while she was at work, Jones resigned from her position in April 2016. She was able to find a job where she could work from home in June 2016, which let her stay close to her children and husband. But the family fell behind on rent; they were evicted and went to live with Solomon’s sister in February 2017.

Check the following resources for caregivers.

The American Psychosocial Oncology Society has a hotline that both patients and caregivers can call to get advice on mental health and emotional support resources in their communities.

The Cancer Support Community provides online advice and information for cancer caregivers, a help line and support programs at local affiliates.

CancerCare hosts virtual and in-person support groups and workshops for cancer caregivers.

The Answer Cancer Foundation hosts an Advanced Cancer Caregiver Virtual Support Group so that caregivers for loved ones with metastatic disease can connect, regardless of cancer type.

The Home Alone Alliance offers video series tailored for family caregivers on mobility and wound care, with more topics to come.

The National Cancer Institute provides a booklet, Caring for the Caregiver, that includes guidance on making time for yourself, navigating complicated feelings and asking for help.

The American Cancer Society provides a guide for caregivers and family members of people with cancer, including guidance on self-care, supporting your family member, and navigating issues like health insurance and leave from employment.

Caregivers Become Patients

On top of financial repercussions, caregiving can lead to physical and emotional problems for the caregivers. “Many caregivers report substantially worse quality of life than the national average,” says Joanne Buzaglo, senior vice president of research and training at the Cancer Support Community, which maintains a registry of caregivers’ experiences. According to an August 2017 report based on the registry records, cancer caregivers have significantly elevated anxiety, depression, fatigue and sleep disturbance, as well as impaired social functioning.

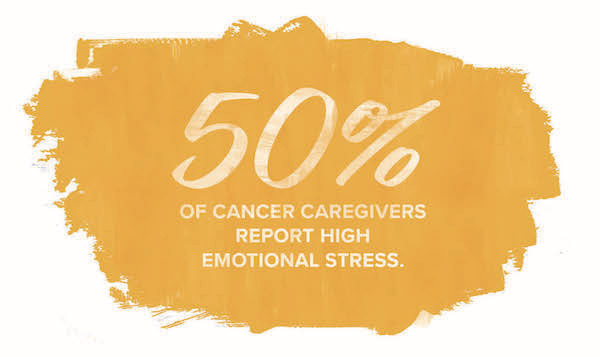

Statistic from Cancer Caregiving in the U.S.

An April 2017 study published in Psycho-Oncology indicated that caregivers of patients with advanced cancer are three times more likely than average to be diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and 7.7 times more likely than average to be diagnosed with major depression.

Jones recalls going to the cafeteria at the hospital where her husband was being treated and feeling like her heart was going to jump out of her chest and she was going to faint. “I had never felt like that,” she says. Her doctor told her she was having anxiety attacks. As time passed and her financial problems increased, she also became depressed.

In fall 2016, she went to see a therapist, who asked her what she liked to do. Jones didn’t have an answer. “That’s when I figured out I had lost myself,” she says. “I hadn’t taken time out for myself in a very long time. Everything was about my kids and my husband.”

Caregiving is also associated with neglect of the caregiver’s own medical appointments and preventive care. “What we now know very clearly is that caregiving is bad for your health,” says Ferrell.

When Leonard’s husband was first diagnosed with stomach cancer in 2012, she recalls going down several pants sizes because she wasn’t eating. She eventually developed shingles, which she suspects resulted from the constant stress of juggling caring for him and their children, and working. “I did absolutely nothing for myself,” she says. When her husband’s cancer returned in March 2017, Leonard vowed to schedule time to take care of herself and to ask for help from friends and family.

Researchers are trying to incorporate more caregiver support into the health care system. Clinical trials have shown that various programs in which nurses or other providers offer education and support to caregivers improve quality of life. But while caregivers may find support through participation in research studies, few tested interventions make it into regular practice because of a lack of health insurance reimbursement for these types of services.

Some cancer centers and nonprofit organizations offer support groups for caregivers, but caregivers may find it difficult to find time to go. A group will meet, say, “every second Tuesday from 2 to 4 in the afternoon … which is wonderful, fabulous, but probably 10 people are there,” says Ferrell.

Caregivers are increasingly finding help from each other virtually, whether by joining internet forums, connecting to each other through nonprofits or starting their own online groups. Louwers was able to connect with other caregivers who have loved ones with advanced cancer in the online forum Inspire.com, which has communities for caregivers and patients with a variety of cancer types. Leonard is part of the Debbie’s Dream Foundation Patient Resource Education Program, which connects stomach cancer patients and caregivers to mentors who can give them advice online or by phone. She has had multiple mentors and also mentored at least two dozen other caregivers.

For Jones, learning to take time for herself has included making soaps and helping to connect other colon cancer caregivers. In April 2016, she started the Colon Cancer Caregiver Support Group on Facebook, a private group that now includes more than 400 members. In her group, she says, caregivers share practical tips about ostomy bags, nausea and palliative care. They also just vent. Jones and her family moved into their own home in September 2017, and she hopes to start an in-person group at her local cancer center.

Jones’ advice to new caregivers? Remember that taking care of your mental health is as important as taking care of those around you. Even if you are experiencing emotions that seem impossible to express, she adds, there are people out there who will understand. As caregivers, “we may not go through the same things, but you’re not alone. Somebody is here with you.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.