YOU MIGHT CALL BILLY FOSTER a jazz evangelist: He can’t help but share his passion. Foster converted Bruce Evans, his friend of 50 years, back in 1965 when they were students at Defiance College in Ohio. Although Foster was majoring in classical piano, he was drawn to the improvisation and rhythm of jazz, and he urged Evans to listen with him as he played jazz recordings from his vast collection.

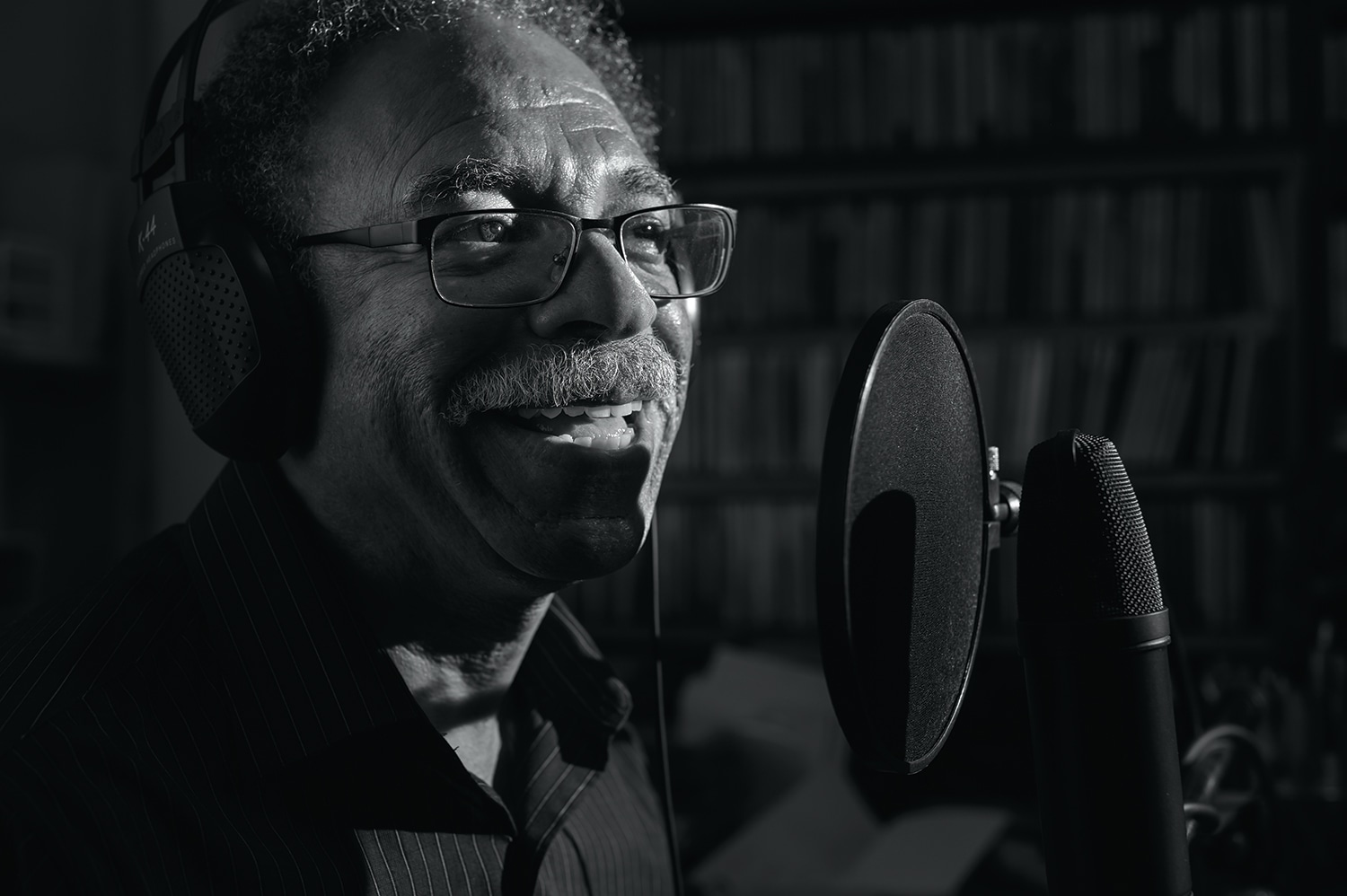

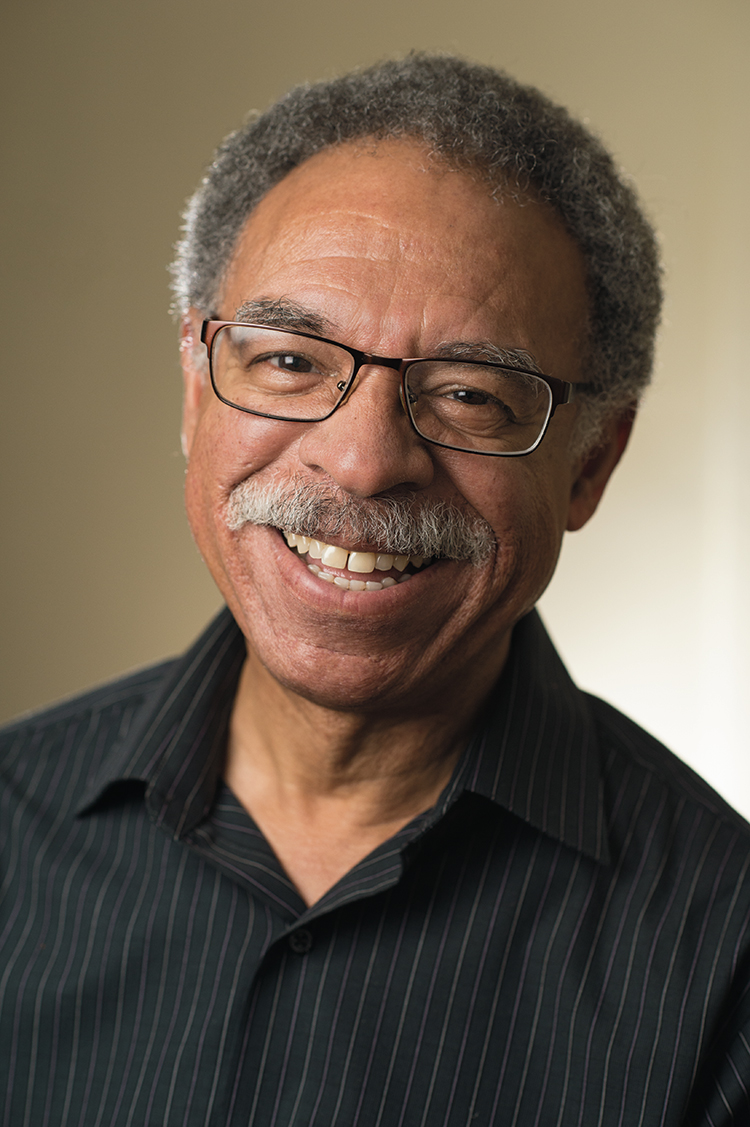

Billy Foster Photo by Ken Carl

“Invariably, when I visited him in his dorm, the time would evolve into a marathon listening session,” says Evans, who today plays bass in Foster’s band, the Billy Foster Trio. “I can still hear him saying, ‘Bruce, you just gotta listen to this track before you go.’ ”

“There’s so much to the music,” says Foster. “You can never get tired because you never learn it all. You’re constantly learning. That’s what also makes it so great.” Half a century after those dorm room listening sessions, Foster, now 66, remains on that same jazz-driven mission—playing and performing, teaching and composing, and even hosting his own local radio show, the Billy Foster Jazz Zone, which he records at his Gary, Ind., home. He’s determined to spread his love of jazz, especially to younger generations.

In recent years, jazz has also given Foster a personal outlet during a difficult time—a way to express himself and cope since his cancer diagnosis and through treatment. “I would say that jazz is a centerpiece in Billy’s life,” notes Evans. “He loves to perform, compose and share his passion for jazz—all of which, I believe, helps to give him a focus and purpose for living.”

Living in the Moment

To anyone who knows Foster, it comes as no surprise that his favorite room at home is the piano room. There, you’ll find a Baldwin grand piano, recording equipment and countless jazz CDs and albums.

At home in his piano room, Billy Foster finds that jazz improvisation has been a welcome outlet to express himself during years of cancer treatment. Photo by Ken Carl

A lifelong musician, Foster began playing piano at 7 and taught himself jazz piano in college. He later honed his skills by taking lessons from Jaki Byard, a well-known American jazz pianist, while living in New York City in the 1970s. Today he plays piano and composes music for two trios: the Billy Foster Trio, which he started in 1967, and the Valparaiso University Faculty Jazz Trio, a group he co-founded in 1980, the same year he began teaching jazz piano at Valparaiso University in Indiana. The trios’ itineraries include performances at high schools, where Foster—who is also a retired public elementary school music teacher of more than three decades—hopes to spark an interest among his young audiences. When he’s not performing with the trios, he performs solo, playing at the Strongbow Inn in Valparaiso each Sunday.

It’s a schedule he’s kept up—and found comfort in—even through cancer. Initially diagnosed with stage I kidney cancer in 1996, Foster quickly underwent surgery to remove the affected kidney. But in 2007, a persistent cough led doctors to discover that the cancer had returned and spread to his lungs, liver and brain. His doctors recommended an oral drug, Sutent (sunitinib), which had been approved the previous year by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of metastatic kidney cancer.

Despite difficult side effects, including nausea and high blood pressure, Foster stuck to his scheduled performances. “Sometimes we’d have to pour him into the car,” says his wife of 15 years, Renee Miles-Foster. “But he was determined to go and play.”

In 2008, when Foster’s cancer did not respond to the Sutent, he joined a clinical trial of an investigational drug. After that drug was discontinued in 2013, Foster started another new medication, Inlyta (axitinib), and his cancer is currently stable. He knows his disease is incurable, yet the ability to compose and perform jazz, he says, has steeled his mind against negative thoughts and the endless “what-ifs.”

Jazz, he explains, is about improvisation and living in the moment.

Progress has been made in the approval of new therapies for kidney cancer.

In 2013, just over 65,000 Americans were diagnosed with kidney cancer, including more than 40,000 men and nearly 25,000 women, according to estimates by the American Cancer Society. The same year, almost 14,000 men and women died of the disease.

More than three-quarters of kidney cancer patients diagnosed at stages I and II and more than half of those diagnosed at stage III will survive for at least five years. The prognosis for metastatic disease is much less positive, with fewer than one in 10 patients diagnosed at stage IV surviving for five years.

But recent progress has been made in the approval of new therapies for advanced kidney cancer. Since 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved seven new drugs for its treatment: Nexavar (sorafenib), Sutent (sunitinib), Torisel (temsirolimus), Afinitor (everolimus), Avastin (bevacizumab), Votrient (pazopanib) and Inlyta (axitinib).

More research is underway. To find kidney cancer clinical trials, visit www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search and choose “Kidney (renal cell) cancer” from the drop-down menu.

Spreading the Word About Jazz

Next door to Foster’s home is a small house where he holds rehearsals for the Billy Foster Trio and teaches private piano lessons. The house also includes a small recording studio for his eight-year-old radio show, which airs on WGVE 88.7 FM from 10 a.m. to noon on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays. (Recent shows are available online at billyfosterjazzzone.com.)

The show was his wife’s idea. After listening to her husband talk endlessly about jazz, she recalls, she drove to the local public radio station in 2005 and spoke to the managers. “I told them my husband needs to have a radio show,” Miles-Foster says with a laugh. “He’s got too much that he knows about and he needs to tell somebody something.”

Billy Foster performs with Bruce Evans, on bass, and Lannie Turner, on drums, in the Billy Foster Trio. Photo by Ken Carl

Ask Foster if he enjoys being a radio show host, and he will answer simply in his mild-mannered tone, “I like it a lot. It’s fun.” But ask him why he likes doing the jazz show and you’ll hear the evangelist come out. “I think it’s a very important music. It’s one of the only art forms created here in the U.S., and so it’s important just from that standpoint,” he says. He also feels a responsibility to pass on the tradition of jazz music. “So my thing is to keep it out there and expose it as much as possible.”

Clinical trials offer hope for metastatic kidney cancer patients.

More than a decade after jazz musician Billy Foster was treated for kidney cancer in 1996, he learned that the cancer had returned, spreading to his lungs, liver and brain. In 2007, a gamma knife procedure removed the brain lesions. But when Sutent (sunitinib)—a type of targeted drug known as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor—couldn’t keep his other tumors from growing, Foster enrolled in a clinical trial in 2008 and began taking an experimental oral drug.

The new treatment helped shrink a few tumors in Foster’s lungs and liver and stabilized them. Then, in June 2013, Foster says, his doctor told him that the drug’s maker was halting production because the clinical trial had shown that most patients were not benefiting from the treatment. Foster’s doctors searched for a similar drug and found the tyrosine kinase inhibitor Inlyta (axitinib), which had been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 to treat advanced kidney cancer. In October 2013, Foster’s first CT scan since starting Inlyta showed his cancer wasn’t growing, suggesting the drug was helping to keep his cancer in check.

The fact that new treatment options for kidney cancer have become available in just a few short years gives Foster hope. He says he’s fortunate to have benefited from clinical trials—both from the research done that helped to develop the FDA-approved treatments he has had, and from the drug he received during his trial.

Clinical trials can be viewed with skepticism, Foster notes, but he is hoping to change that perception. During his jazz radio show, he shares his cancer story, along with resources, to help inform and educate his listeners about cancer and clinical trials.

Foster says that doctors told him in 2008, when Sutent wasn’t working for him, that if they couldn’t find something to stop his cancer, he’d be dead in a couple of years. “That made a clinical trial look all the more attractive,” he says with a chuckle. “There’s a good chance I wouldn’t be here were it not for clinical trials.”

It’s not that Foster really believes that jazz will completely die out. But over the years, he has witnessed a shift in the music scene.

The number of jazz venues has declined greatly across the country, he explains. A few decades ago, even movie theaters would sometimes host jazz performances: As a child, growing up in Gary, Foster would go with his parents to see movies in nearby Chicago and be entertained by live jazz performers before the films began. “There was a theater over there called the Regal and another one called the Tivoli, and they would bring in jazz artists like Duke Ellington and Miles Davis,” he recalls.

Today, young musicians who have studied jazz in college have fewer spots to showcase their skills. “When I was coming along,” he says, “there used to be 30 different places you could play” in one city.

Foster’s wife, Renee Miles-Foster, who often sings with his band, encouraged him to start a radio show. Photo by Ken Carl

Foster is encouraged that high schools are exposing students to jazz through school bands. But once these kids graduate, he says, they won’t have many places to play or outlets for listening to the music.

Through the radio show, “that’s something I hope that I provide,” he says. On the air, Foster usually features the music of current artists, such as Monty Alexander, Roy Hargrove and Wynton Marsalis. But he also will play past masters, featuring the lineage accompanying a specific jazz instrument, like the trumpet, beginning with Louis Armstrong and progressing chronologically through artists such as Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis.

Young people, in particular, “need a place to listen to the music,” he says. If Foster has anything to do with it, he’ll continue to ensure that jazz keeps reaching a new generation of listeners.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.