When is a cigarette not a cigarette? For now, when it’s an electronic cigarette, also known as an e-cigarette or electronic nicotine delivery system. But that might change soon. Within the next few months, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will announce whether it will regulate e-cigarettes in the same way it does tobacco products.

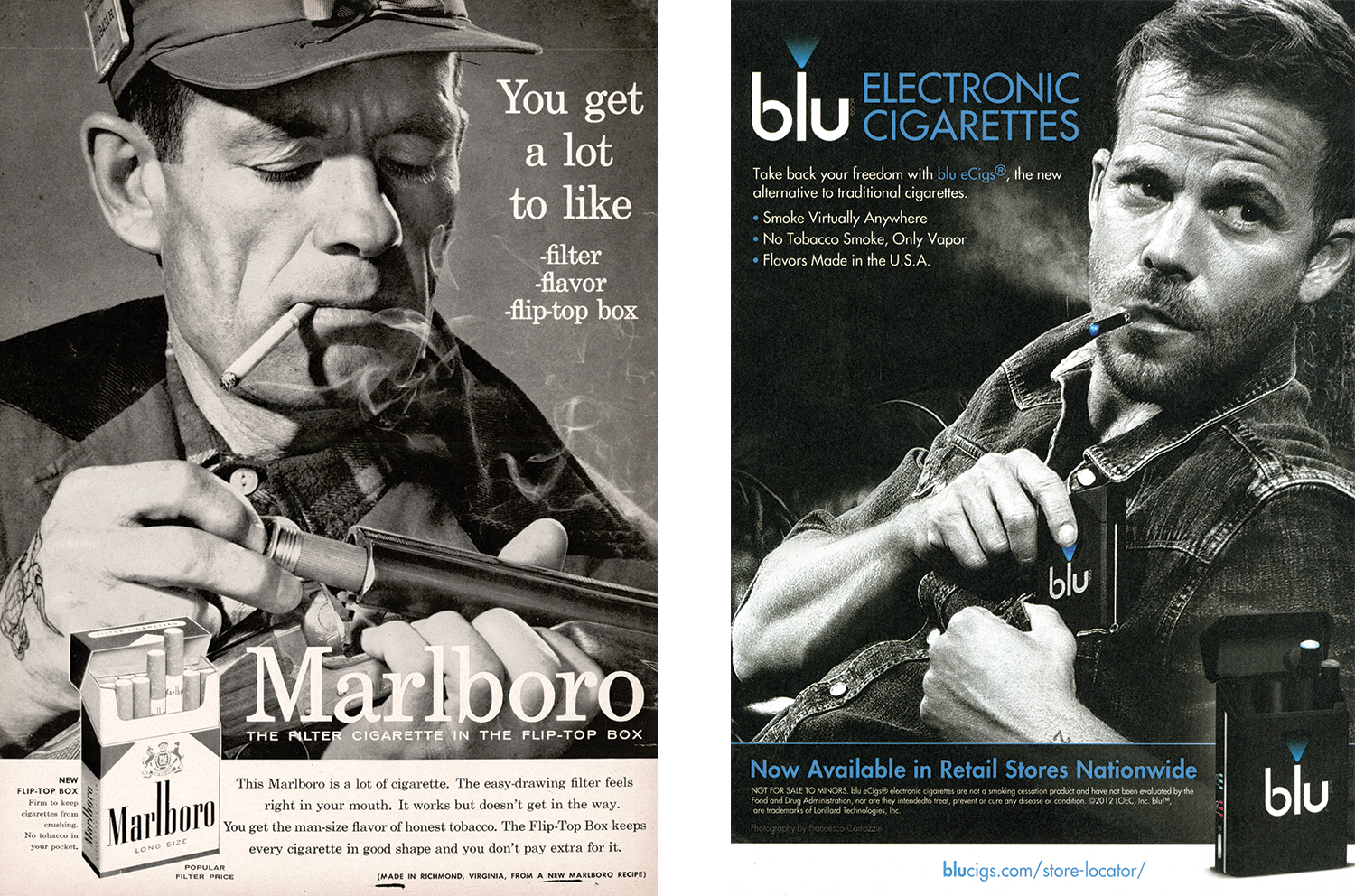

E-cigarettes quietly appeared on the U.S. market in 2006, but their use has skyrocketed in the past few years. The number of adult smokers using e-cigarettes doubled between 2010 and 2011, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. With increased use has come sizable revenue for their manufacturers—estimated at $2 billion worldwide—and increased interest from Big Tobacco, which is pursuing the e-cigarette market. Lorillard, the third largest tobacco company in the U.S., purchased Blu, a top-selling brand of e-cigarettes, in 2012.

All e-cigarettes contain three standard components: a power source, such as a rechargeable battery; a heating element activated by inhalation; and a cartridge containing nicotine attached to the heating element on one end and a mouthpiece on the other. When a user inhales, the heating element vaporizes the nicotine solution. The resulting mist is pulled into the mouth and lungs. Some e-cigarettes feature sweet flavors like bubble gum or cookies and cream.

E-cigarette manufacturers say their products will help current smokers avoid tobacco’s dangers. But whether they are effective in helping smokers quit isn’t clear. A small smoking cessation trial, published Nov. 16, 2013, in the Lancet, found that short-term quit rates were similar for smokers given e-cigarettes or nicotine patches. But more and larger studies are needed to reach definitive conclusions, experts say.

“We don’t know yet whether people who really like e-cigarettes will totally switch off tobacco cigarettes,” says Neil Benowitz, an internist and pharmacologist at the University of California, San Francisco. “If they do, that’s really a positive. If they don’t, and they keep on smoking regular cigarettes sometimes and e-cigarettes sometimes, then that’s going to be bad.”

The FDA is considering a range of regulations. It could, for example, decide to place limits on the contaminants allowed in e-cigarette cartridges or bring the products’ advertising, marketing and flavorings in line with those for tobacco cigarettes. It may also decide to require manufacturers to disclose the contents of their nicotine cartridges. Recent research by Benowitz and his colleagues, published online in Tobacco Control on March 16, 2013, found toxic substances in a selection of 12 e-cigarette brands, though at levels significantly lower than in cigarette smoke. How these levels of toxicity might affect human health is another area without much scientific data.

Anti-smoking groups, which are pushing the FDA to quickly bring e-cigarettes under its regulatory umbrella, are concerned that e-cigarette use could delay smokers’ attempts to quit and reverse decades of effort that went into developing strict smoke-free laws across the nation.

“We believe e-cigarettes should be included in smoke-free laws,” says Danny McGoldrick, the vice president of research at the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids.

“We also need e-cigarettes to be regulated like conventional cigarettes in terms of restrictions on sales and marketing,” McGoldrick adds. “No sales to kids, put the products behind the counter, disclose the ingredients, no flavorings. These are all things that are required of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco by the FDA.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.