When Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s musical The King and I opened on Broadway on March 29, 1951, expectations were high. The famed songwriting team had already created four hit shows, and the role of Anna was to be played by theater star Gertrude Lawrence, whose name blazed across the top of the marquee. Less attention was paid to the relatively unknown actor Yul Brynner, who had been cast as the King. But after opening night, no one would forget his name.

The King and I is about the relationship between the King of Siam and a widow, Anna, who teaches English to his children. The role wasn’t created for Brynner, but Brynner was made for the part. As New York Times theater critic Frank Rich wrote in January 1985, when Brynner returned to Broadway with The King and I for the third time: “Mr. Brynner is, quite simply, The King. Man and role have long since merged into a fixed image that is as much a part of our collective consciousness as the Statue of Liberty.”

Rich’s piece was equal parts review and tribute, as it was widely known that Brynner had been diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer 16 months earlier. The secret had gotten out when Brynner’s voice grew hoarse from his radiation therapy, forcing his touring production of The King and I to close. But as soon as he learned that the treatment had slowed his tumor’s growth, the 63-year-old actor, who had recently married for the fourth time and was a father of five, quickly returned to his role. Regrettably, metastatic lung cancer doesn’t take direction from anyone, not even a king as commanding as Brynner. His final curtain call—his 4,633rd performance as the King—was on June 30, 1985. He died on Oct. 10, less than four months later. To this day, no one has performed a part as many times.

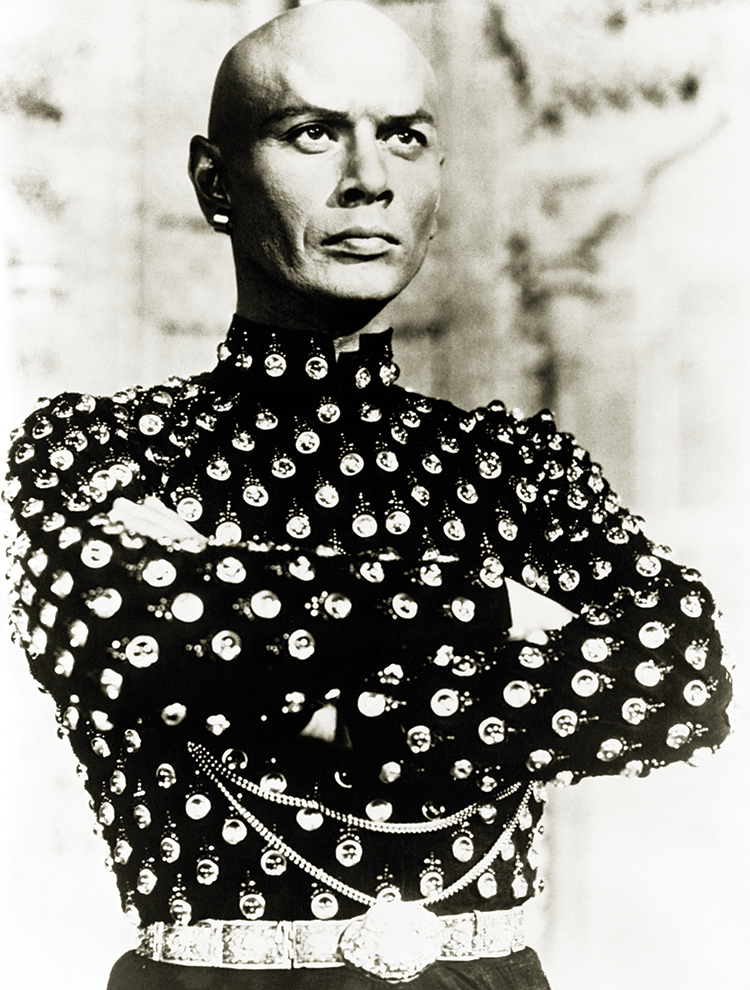

By the mid-1950s, Yul Brynner had won both a Tony Award and an Oscar for his performances in The King and I. Photo © Bettmann / Corbis

An International Upbringing

Yul Brynner was born Juli Borisovitch Bryner, in Vladivostok, Russia, on July 11, 1920, the second child of Boris Bryner and Marousia Blagovidova. (He added the second “n” to his last name years later, so that English speakers would pronounce it properly.) Vladivostok is a port city located in the southeastern region of Russia, close to the Sea of Japan. As Yul Brynner’s son, Rock, explains in his book Empire & Odyssey: The Brynners in Far East Russia and Beyond, for three generations the family’s choices were closely intertwined with the city’s location and the wars that encompassed the region.

Yul Brynner’s grandfather Julius Bryner moved from Switzerland to Vladivostok in the 1870s, established a successful import-export company, and went on to become one of the city’s most respected businessmen. Boris Bryner followed in his father’s footsteps; when Vladivostok became part of the newly established (and short-lived) Far Eastern Republic in 1920, during the Russian Civil War, he was asked to serve as minister of industry.

Boris Bryner’s high-powered position required extensive travel, and when Yul was 3, his father left his mother for a woman he had met in Moscow. To escape ongoing regional conflict, Yul’s mother moved him and his older sister to Harbin, China. But as war loomed between China and Japan, she feared a Japanese invasion of Harbin, and in 1932 she moved the family to France. There, Yul’s dreams of becoming an actor blossomed as he played guitar in Russian nightclubs in Paris, trained as a trapeze acrobat and joined a theater company. But Paris was not home for long. In 1938, Yul’s mother was diagnosed with leukemia, and, fearing that the Germans would soon invade France, she and Yul moved back to Harbin. By 1940, it became clear that he could no longer care for his mother alone, and the two moved to New York City, where his sister lived.

The young Yul Brynner barely spoke English when he arrived in New York City in 1940. Photo © Condé Nast Archive / Corbisoto

The Lights of Broadway

When he arrived in New York, Brynner barely spoke English. But that didn’t stop him from heading off to Connecticut to study acting with the renowned Russian teacher Michael Chekhov. There, he learned how to use his voice and body and began to embrace what it meant to be an actor. “When you are a pianist,” Brynner later explained, “you have an outside instrument that you learn to master through finger work and arduous exercises. ” … As an actor, you the artist have to perform on the most difficult instrument to master, that is, your own self—your physical and your emotional being.”

Brynner’s first Broadway performance was a small part in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night in December 1941. Over the next few years, his acting opportunities were few, and Brynner decided to follow his first wife, actress Virginia Gilmore, to Hollywood, where he found work as a director at the new television station CBS. His path seemed set. Then in 1950 a friend convinced him to return to New York City to audition for the King.

Virtually overnight, Brynner became a household name. In 1952, he won a Tony Award for his performance in The King and I, and when the play was made into a movie a few years later, there was no question the part was his. Brynner proved to be as good on film as he was onstage, winning the 1956 Academy Award for Best Actor. Over the next two decades, Brynner appeared in more than 40 other films, but it was the role of the King that he returned to time and time again.

A Cancer Diagnosis

In September 1983, Brynner made an appointment to see his physician after finding a lump on his vocal chords. (He had been diagnosed with a precancerous lump on his larynx just the year before.) Brynner was in Los Angeles, with only three hours to go before he took the stage for his 4,000th performance, when he received the test results. The new lump was merely an enlarged gland, he learned. But there was a much bigger problem: He had lung cancer, and the tumor was too close to his heart to attempt surgery.

Initially, Brynner was determined to keep performing. But ultimately he had to admit that the radiation therapy, which was his only option for treatment, had made his throat so painful he could no longer act. It also became clear that the public wasn’t eager to watch an esteemed actor struggling with the effect cancer was having on his performance. “He called me one day to tell me ticket sales were falling off,” says Rock. “ ‘Cancer,’ he complained, ‘is a real poison at the box office.’ ”

Lung Cancer’s Toll

When Brynner was diagnosed, lung cancer was the leading cause of cancer deaths among American men, and the second-leading cause of cancer deaths among American women. It is now the leader among both men and women, with more Americans dying of it than of colon, breast and prostate cancer combined. The American Cancer Society estimated that in 2011 about 221,000 Americans would be diagnosed with lung cancer, and that about 157,000 would die of it, making the disease responsible for about 27 percent of all U.S. cancer deaths this year.

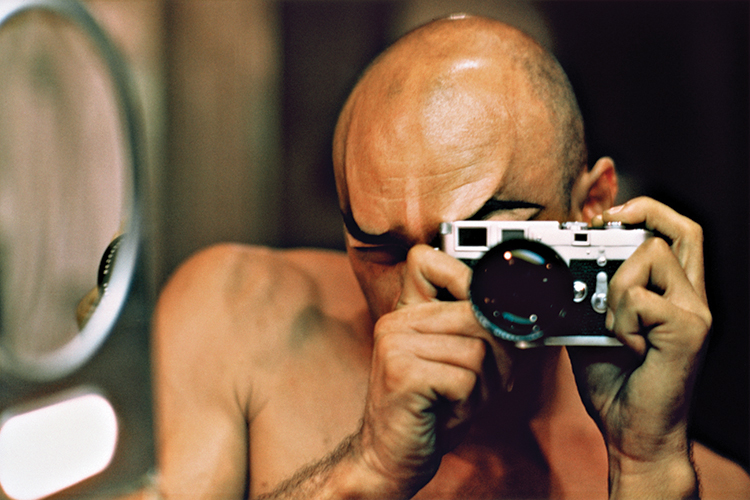

In his personal life, Brynner discovered a passion for photography (above, in a self-portrait behind the scenes of The King and I in 1956) Photo courtesy of Victoria Brynner

Yet many people remain unaware of lung cancer’s toll. A recent survey of 1,000 Americans conducted by the National Lung Cancer Partnership, a nonprofit patient support organization, found that nearly 80 percent of the respondents didn’t know that the No. 1 cancer killer in the U.S. is lung cancer. This is due, in part, to the fact that there are few long-term survivors. “Because lung cancer has a [five-year] survival rate of only 15 percent, you don’t have that mass of survivors who want to stand up and give back and say thank you for saving my life,” says Kim Norris, the president of the Los Angeles–based Lung Cancer Foundation of America. The lack of public awareness is also connected to the smoking-related stigma attached to lung cancer, she says. “Even family members can become victims of the stigma and be hesitant or unwilling to become an advocate or donate to an advocacy organization,” says Norris, “because they believe their loved one did this to themselves.”

The stigma attached to lung cancer also affects both government funding and corporate donations. Regina Vidaver, the executive director of the National Lung Cancer Partnership, explains that if you look at cancer funding through the lens of each cancer’s contribution to cancer deaths, lung cancer receives a disproportionately small share of the funding pie. In 2009, the National Cancer Institute’s research budget allotted just under $247 million for lung cancer, compared with $294 million for prostate cancer, and about $600 million for breast cancer.

Treatment Advances

Despite this funding disparity, lung cancer treatments have advanced in important ways since Brynner’s death in 1985. If Brynner had been diagnosed today, says Daniel Morgensztern, a clinical oncologist at the Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Conn., “I think his odds might have been better.” Improved surgical techniques, he says, might have made it possible for Brynner to have surgery, despite the tumor’s proximity to his heart. He’d also have had a PET scan (a technology that wasn’t widely available until 1998) to see if the tumor had spread to other organs. This would have helped to determine his treatment.

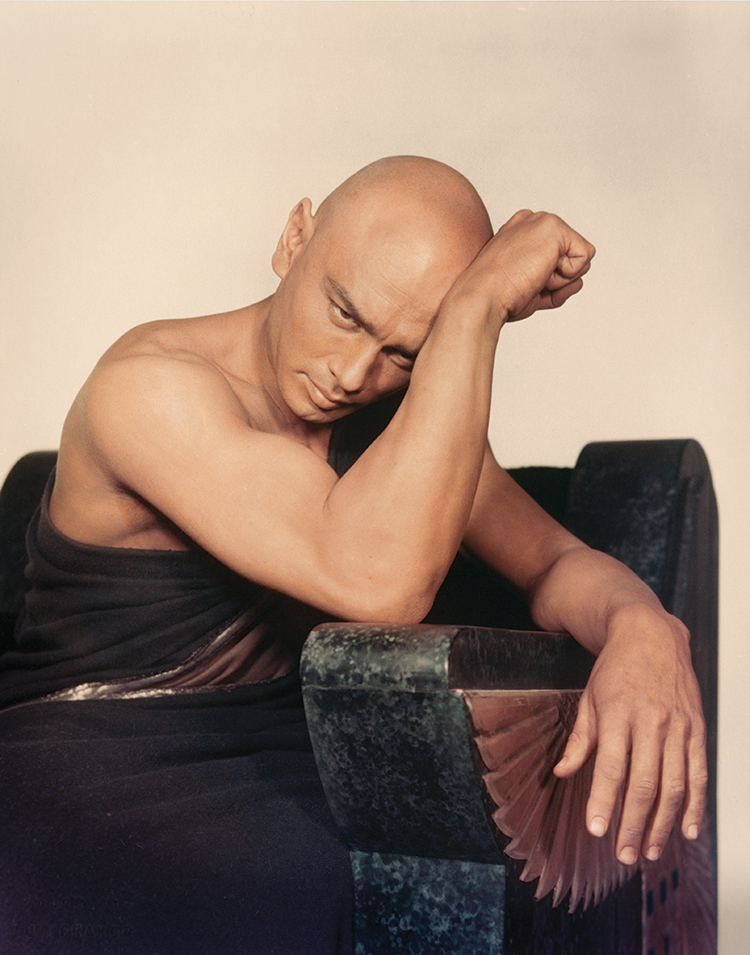

Yul Brynner starred in more than 40 movies, including the 1956 film The Ten Commandments. But shortly before his death, the public wasn’t eager to watch him struggle with the effect cancer was having on his performances. Photo © Cinemaphoto / Corbis

Brynner also would have been offered more treatment options. The type and stage of Brynner’s lung cancer are unknown, but it’s likely he had non-small cell lung cancer. If he was stage III, says Morgensztern, he’d probably have had chemotherapy in addition to radiation. If he was stage IV, his tumor would have been tested to see if he was a candidate for one of the targeted therapies that in the early 2000s began to be approved for the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer.

One of these drugs is bevacizumab (Avastin), which can disrupt angiogenesis—the growth of the blood vessels a tumor needs to survive—by blocking a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Others are therapies known as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, which work by blocking a protein that fuels tumor growth. These drugs—erlotinib (Tarceva), gefitinib (Iressa) and cetuximab (Erbitux)—are effective in only lung tumors that test positive for the EGFR genetic mutation. The most recent targeted therapy option is crizotinib (Xalkori), a drug that inhibits a biochemical pathway called anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), which promotes tumor growth. It received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in August 2011 for the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer that has an altered ALK gene. Studies suggest that about 3 to 5 percent of non-small cell lung cancers have this alteration.

A Dramatic Ending

Brynner was well aware that although he’d quit smoking in 1971, he was still at risk of developing lung cancer, says Rock. He’d smoked two-to-four packs a day since the age of 12, and “he was always holding a cigarette in the photos he chose for his publicists to distribute to his fans.”

In an effort to educate others about the risks of tobacco, Brynner orchestrated the creation of an anti-smoking commercial a few months before his death. He arranged an interview on Good Morning America, and he made a point to emphasize the importance of not smoking. Then, working with the American Cancer Society, he used a clip from his interview to create a public service announcement. Within days of his death, the PSA was running on the three major U.S. television networks, as well as on other stations throughout the world. For 30 seconds, his brown eyes stared into the camera, his distinctive voice uttering one last haunting plea: “Now that I’m gone, I tell you: Don’t smoke. Whatever you do, just don’t smoke.”

The idea that Brynner would have orchestrated a commercial that would influence how he was perceived decades later didn’t surprise anyone who knew him well. “He was the Emperor of the Universe,” says Rock. “Not just the King or the Pharaoh. He controlled everything within earshot and beyond. ” … From age 12 he learned how to seize control of every eyeball in a room.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.