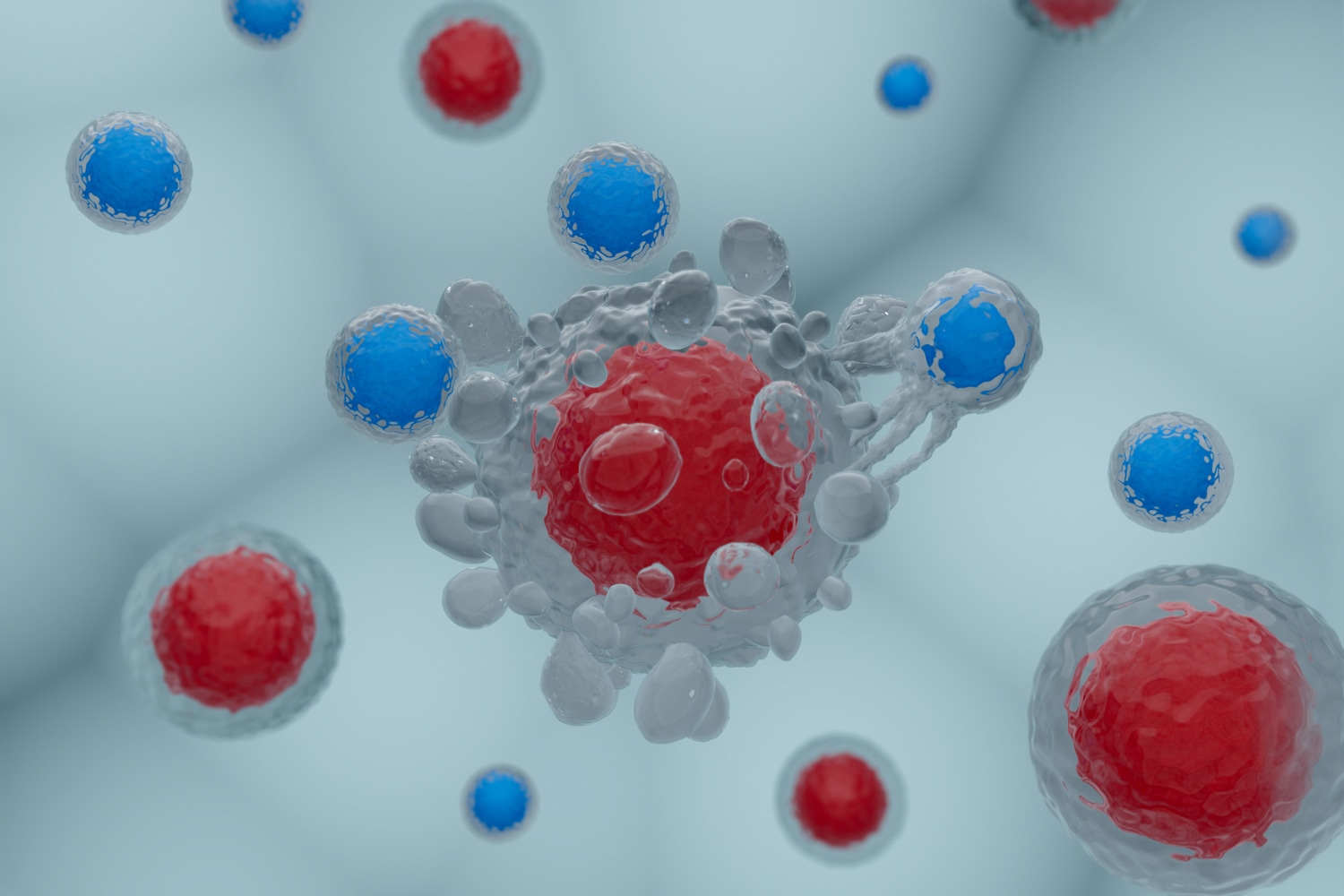

CAR T-CELL THERAPY has emerged as a promising treatment for some types of blood cancer, including large B-cell lymphoma. The treatment involves extracting immune cells from a patient’s body and modifying them with a gene that makes receptors (or CARs) that bind to a protein on cancer cells. The modified immune cells are then returned to the patient’s body, where they seek out and attack cancer cells.

Often, the treatment is effective at first, but the disease eventually progresses in more than half of patients with blood cancers. A paper published August 2021 in Nature Medicine set out to address disease relapses by engineering a CAR T cell that binds to not one but two proteins—CD19 and CD22—found on the surface of cancer cells. Immunologist Crystal Mackall, a member of the research team at Stanford University in California that produced the study, spoke with Cancer Today about what she and her colleagues learned about why CAR T-cell therapy works in some patients but not others.

CT: In a nutshell, how does CAR T-cell therapy work?

MACKALL: Like all immunotherapies, CAR T-cell therapy is focused on enhancing the patient’s immune system and giving it the power to attack the tumor. We’re taking the actual immune cells out of the body, into a flask, and culturing them with a disabled virus that delivers a genetic payload. That genetic payload integrates into those cells so that those cells and all the daughter cells are modified to express this molecule that we call a CAR, or a chimeric antigen receptor. I liken the CAR to a bloodhound. You’ve given it the scent of the tumor, and then the cell will seek out the tumor and attack.

CT: In general, how effective is CAR T-cell therapy for patients with blood cancers?MACKALL: We focused here on diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. With those tumors it is about 40% effective. In some ways, the glass is half full because this is an entirely new therapy that is providing curative options for patients for whom there really wasn’t anything else at that stage of disease. But the glass is half empty because disease will progress for more than half of these patients. This paper is trying to understand the resistance—why do 60% progress?—and to create a new approach that would increase the rate of effectiveness beyond 40%.

CT: What questions did you set out to answer?

MACKALL: The first part of the paper tried to answer the question, why do more than half of large B-cell lymphoma patients progress? We all know it happens, but the truth is that the field hasn’t had a good understanding of the basis for resistance. We were trying to figure out how often the problem lies with CD19, either a loss of it or not enough of this target on the cancer cells. In the second part of the paper, [we asked] if two-thirds of patients experience progression because there isn’t enough CD19 around, can we prevent this by going after two targets at the same time?

There are now a couple of studies, including ours, that have demonstrated that about a third of patients who progress lose CD19. It’s gone. Where I think we added an important insight is that we understand that you don’t need to completely lose a target for CAR T cells to ignore the tumor. In other words, the tumor can escape by down-modulating the target. This is one of the Achilles’ heels of CAR T cells—they need a fair amount of target to work.

CT: In this study, you found that it was difficult to engineer CAR T cells that were equally potent against both CD19 and CD22. Where do you go next?

MACKALL: The first attempt wasn’t as potent as we would like, but we have a lot of tricks up our sleeves as to how we can [engineer] CAR T cells that can bind to two or three target proteins equally potently. So we’re not discouraged.

CT: What do these findings mean for patients with blood cancers?

MACKALL: One of the things that we learned is that CD22 is actually a good target. In fact, we have already published data showing that many patients for whom the CD19 CAR fails can be treated with a single CD22 CAR. So, there is hope for those patients. We’re very excited about being able to offer a salvage regimen for those patients for whom the CD19 CAR is not effective.

In the field of B-cell malignancies, it’s just an unbelievable time for progress. There are the CAR Ts and there are antibodies and other biologically based therapies. For patients for whom the standard therapies are not working, research studies are showing great promise in this space right now.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.