WHEN 52-YEAR-OLD TERRY EVANS learned that he had chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in 2000, he didn’t look or feel sick. But Evans’ white blood cell count had been increasing gradually each year on routine blood tests. Although his counts were only slightly above the normal range, his primary care doctor referred him to a hematologist just to check it out.

At the initial appointment, the hematologist drew some blood but didn’t seem overly concerned. So, when Evans came back to receive the results, he didn’t bring his wife. He was alone when the doctor told him he had leukemia.

“I had no idea what we were talking about,” Evans says. His doctor told him about two available treatments for his type of leukemia: chemotherapy or a blood stem cell transplant. “That’s all there was at the time,” he recalls. Evans, now 72, also remembers reading online that he probably had about five to 10 years to live.

More than 20,000 people are expected to learn they have chronic lymphocytic leukemia this year, and approximately 4,000 people will die of the disease. This kind of blood cancer is the most common type of leukemia in adults. The median age at diagnosis is around 70.

The treatment landscape for CLL, the most common form of leukemia diagnosed in adults, has changed considerably over the past two decades. Using the latest available statistics from 2009 to 2015, the five-year relative survival rate for people with CLL is approximately 85%. In addition, death rates for CLL fell on average 2.9% each year from 2007 to 2016. Evans, a retired computer technology manager and father of four children who are now grown, has been able to take advantage of the new developments as they have occurred.

“I’ve been fortunate to be in the right place at the right time with the right medical team,” he says. “If I had not had access to [newer treatments], I would not be alive today.”

Understanding CLL

CLL is a disease of white blood cells known as B lymphocytes, or B cells. In people with CLL, the body begins making too many of these abnormal B cells, which can compromise the immune system and the ability of the bone marrow to produce other essential blood cell types, including red blood cells and platelets.

Most of the time, the condition comes as a complete surprise due to its incidental diagnosis at an early stage following routine blood tests in people who have no symptoms. But CLL symptoms can include swollen lymph nodes, fatigue, night sweats, fever, unexplained weight loss and tendency to bruise easily.

CLL is generally considered an indolent form of leukemia, which means the condition often progresses slowly. In rare cases, CLL can progress rapidly or transform into more aggressive cancer types. Often, doctors watch and wait before recommending treatment, opting first to closely follow patients to see if they have symptoms, while also monitoring the blood for sharp decreases in hemoglobin and platelet counts, which suggest leukemia is progressing.

“There can be big differences in the time from diagnosis to first treatment [for each patient],” says Shuo Ma, a hematologist-oncologist at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University in Chicago. “It could be months, years or even decades. A small number never require treatment.”

Most people with CLL will ultimately need treatment. And existing drugs are not considered curative, says Ma. Rather, patients will typically experience periods of remission in which the symptoms and markers of cancer will show levels of response to treatment, followed by recurrences, where the cancer shows signs of growth.

Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy

It took seven years after his diagnosis for Evans to show any symptoms. His white blood cell count shot up. He felt tired and lost a lot of weight, and he could feel his lymph nodes were larger. In October 2007, he started a treatment with a cocktail known as FCR, a regimen of two chemotherapy drugs, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, with rituximab. Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to an antigen called CD20 on the surface of both healthy and cancerous B cells, which marks them for destruction by the immune system.

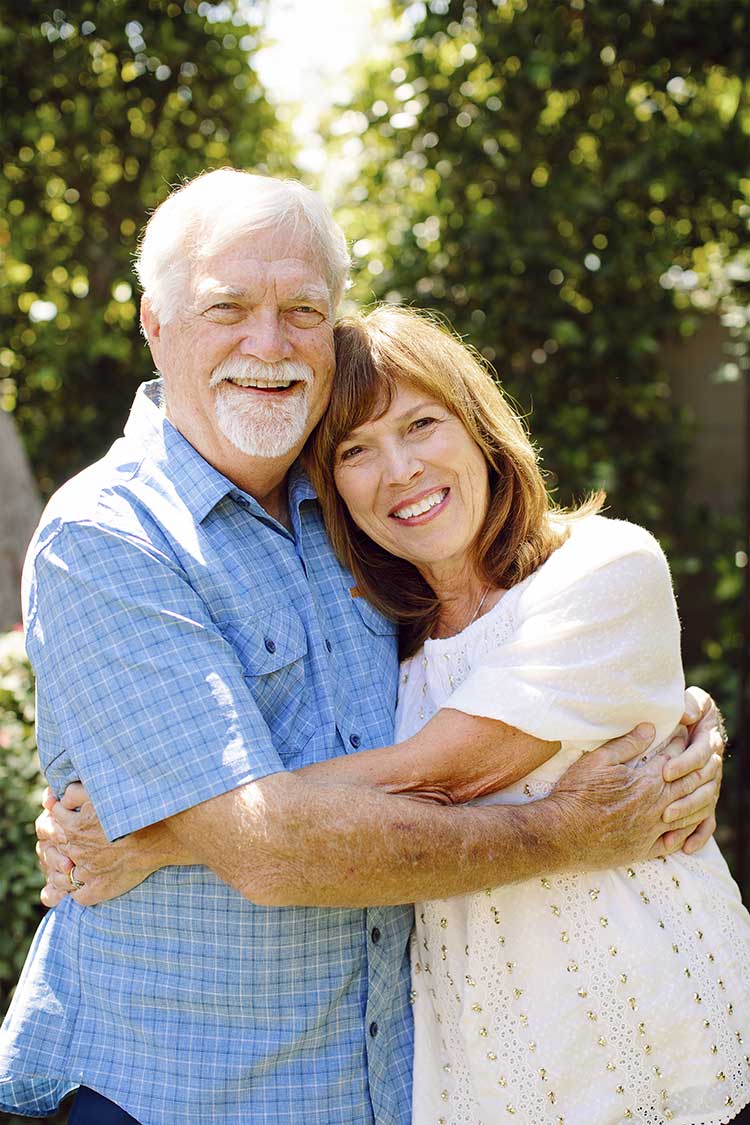

Terry Evans and his wife, Donna, welcomed their 11th grandchild into the world this year. Photo by Natalie Moser Photography

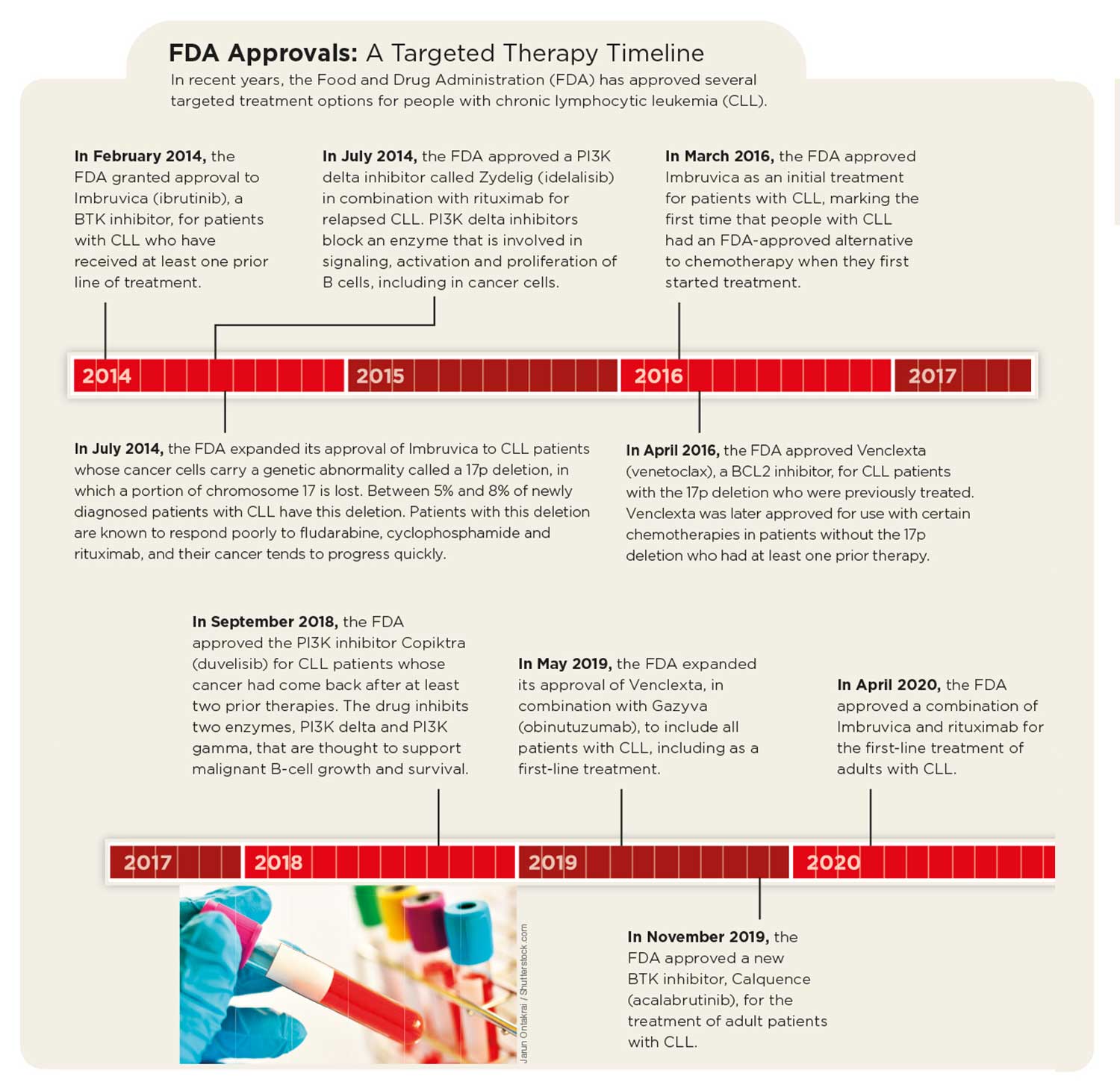

When Evans was first being treated, rituximab had been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for certain types of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but physicians were prescribing the drug for CLL, based on early studies showing positive responses and remissions compared to chemotherapy alone. The FDA approved the chemotherapy and rituximab combination for the treatment of CLL in 2010.

Still, the FCR regimen comes with toxic side effects, especially for older people, who account for most CLL cases. One 2016 study published in Lancet Oncology, for example, shows that among patients over 65, 43% who began FCR treatment didn’t receive the full planned treatment course due to toxicities.

“We needed to look for better treatments that would be better tolerated,” says Ma, who was not Evans’ oncologist.

Even though Evans was younger, he had similar difficulties with the FCR treatment. “To be blunt, it nearly killed me,” says Evans, who had a life-threatening case of autoimmune hemolytic anemia that required multiple hospital admissions and blood transfusions, along with doses of steroids to get it under control.

In June 2008, he started three months of treatment combining rituximab and high-dose methylprednisolone, but the cancer came back 13 months later. In August 2009, he tried the same treatment again. This time, his remission lasted four months.

Most people with CLL are treated on and off for years, says Ma. However, new options that were emerging for Evans then are now providing more alternatives for keeping CLL in check.

A Better Way

In May 2010, Evans enrolled in a clinical trial that was testing a new class of targeted drugs known as BCL2 inhibitors for people whose CLL didn’t respond to available treatment or had come back. BCL2 inhibitors block a protein known to protect cancer cells from programmed cell death.

The study analyzed the use of the BCL2 inhibitor navitoclax (then known only as ABT-263) along with rituximab and another chemotherapy drug called bendamustine. Evans’ cancer responded to the treatment, but he had to stop after nine months due to side effects from the chemotherapy. “I got an 18-month remission out of it [after stopping treatment],” he says. Evans learned that his cancer was chemorefractory, which meant that chemotherapy wasn’t a treatment option for him any longer.

Other targeted therapies would provide new avenues. In October 2012, with his white blood cells again on the rise, Evans enrolled in a clinical trial dubbed RESONATE, which was comparing the efficacy of another new targeted treatment called ibrutinib to an antibody treatment similar to rituximab called Arzerra (ofatumumab) that had been approved in 2009 for CLL patients no longer responding to chemotherapy. Ibrutinib, which went on to be marketed as Imbruvica, blocks an enzyme known as BTK that transmits a signal thought to be critical for the proliferation of abnormal B cells in CLL.

“Leukemia cells don’t survive on their own,” Ma says. “They feed on this signal from the environment in the bone marrow or lymph nodes. When you block this enzyme, you cut out communication between the leukemia and the environment. [The leukemia cells] die by neglect.”

When Evans first joined the trial, he was in the group that received only Arzerra, but his white blood cells started to rise just three weeks after stopping the treatment. In October 2013, he was able to switch over to the experimental treatment arm with Imbruvica, which was already showing impressive early-trial results. He continued this treatment for about 4 1/2 years.

Results from this trial, which included patients with relapsed and refractory CLL as well as patients with relapsed and refractory small lymphocytic lymphoma, were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2014. The findings showed that patients who took Imbruvica had improved progression-free survival and overall survival over Arzerra. A final analysis presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting in June 2019 in Chicago confirmed the targeted treatment’s long-term benefits, showing a median progression-free survival for Imbruvica of 44 months versus eight months for Arzerra.

In January 2018, Evans’ white cell count started to increase, so he enrolled in his third clinical trial, which allowed him to add a new BCL2 inhibitor called Venclexta (venetoclax) to Imbruvica in hopes the combination would control the cancer. He has continued to show a good response to this treatment. In April 2019, he had a flow cytometry test that confirmed the absence of CLL cells in his blood. In October, Evans had a bone marrow biopsy, a more stringent test that measures residual disease, which showed no CLL cells, he says.

“I am not naive enough to think that I’m over all of this, but I will say that this is the first time in over 19 years that they are unable to find any disease,” Evans wrote in in a blog entry posted on Nov. 2, 2019. “I still continue to look at possible next steps, if and when I relapse once again.”

Treatment advances have already given Evans and others like him more ways to manage the disease. In February 2020—nearly two decades after his diagnosis—Evans and his wife took a trip to Arizona to visit their daughter and their 11th grandchild. In addition, two of the targeted treatments that Evans credits with saving his life, the BTK inhibitor Imbruvica and the BCL2 inhibitor Venclexta, are now approved by the FDA as first-line treatment options for CLL.

Today, physicians who are treating patients with CLL typically start with targeted therapies, notes William Wierda, a hematologist-oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who was involved in early research on the rituximab and chemotherapy combination.

Looking Ahead

Questions remain surrounding the use of targeted therapies. It’s not yet clear which class of targeted treatment, BTK inhibitors or BCL2 inhibitors, works best as a first-line treatment for CLL. Ongoing studies are underway to compare them side by side and to test treatment combinations.

In addition to targeted treatments, CAR-T cell therapy, in which a patient’s immune cells are genetically modified and grown in the lab before being infused back in large numbers to attack the cancer, is showing “initially good results” in CLL, notes Wierda. It’s gotten harder to enroll CLL patients in trials for CAR-T cell therapy or other new treatments and treatment combinations because so many CLL patients are doing well with existing treatment options, Wierda says. Still, he hopes to see the list of CLL treatments continue to grow.

“We do think trials offer something that’s potentially better than standard treatment. That’s the goal, and hopefully patients will still seek trials and the treatment options will continue to improve,” Wierda says. “Ultimately, we’re working toward a cure. We’re closer than we’ve ever been.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.