AFTER SHARON LONG was diagnosed with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) at age 53 on Valentine’s Day 2014, she started chemotherapy. She left her job as a nurse in anticipation of the side effects, but the drugs quickly stopped working. Her doctor suggested a clinical trial, recalls Long, who lives in New Haven, Indiana.

When Long joined a trial of the immunotherapy drug nivolumab, later given the brand name Opdivo, in October 2014, she had a lemon-sized tumor under her arm. About half a year later, the tumor was gone. “We got to watch the tumor shrink to where there’s absolutely nothing there,” says Long. “At first I couldn’t imagine watching something shrink like that. It was the coolest thing.”

Aside from some “really minor” symptoms, including watering eyes and a runny nose, joint pain and some fatigue, Long felt good. She stayed on Opdivo, and her other tumors also disappeared or shrank. Then, in October 2017, her tailbone began to hurt, followed by mucus and then blood appearing in her stool. Eventually, she was diagnosed with colitis, an inflammation of the lining of the colon. After three years of minimal side effects while on the drug, her immune system was attacking her gut.

Opdivo, the drug Long took, is called a checkpoint inhibitor. The first checkpoint inhibitor to reach the market, Yervoy (ipilimumab), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011, originally only to treat metastatic melanoma. Six checkpoint inhibitors are now FDA-approved to treat 12 types of cancer. One of these drugs, Keytruda (pembrolizumab), is also approved to treat patients with metastatic solid tumors of any type that have genetic characteristics shown to respond to a checkpoint inhibitor.

Checkpoint inhibitors do not come with the acute, predictable side effects associated with chemotherapy, such as hair loss, profound weakness and nausea. “I call Opdivo the nice drug and chemo the mean drug,” says Stephanie Langell of Long Neck, Delaware, who was diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC in 2015 at age 42 and is currently taking Opdivo. “Obviously, cancer patients always have that fear of cancer coming back, but I think my even bigger fear is that I would have to go back on chemo.”

However, checkpoint inhibitors come with their own diverse side effects, and researchers and health care providers are still learning how to best monitor for them and treat them. Immune-related side effects in the skin and gut, often showing up as rashes and diarrhea, are among the most common. Other frequently affected areas are the musculoskeletal system, the lungs and the endocrine system, which includes the thyroid and pituitary glands. More rarely, patients can have problems affecting the nervous system, heart, eyes, blood or kidneys.

While some side effects, such as heart problems, tend to come on within a month of the start of treatment, others can take months or years to emerge. Many side effects are reversible after patients take drugs, usually steroids, to dial down their immune response. But some immune reactions can lead to lasting damage to organs, or, rarely, death.

“People think everything about the immune system is good, and it’s here to protect us,” says Jedd Wolchok, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Wolchok was a key investigator for the trial that led to the approval of Yervoy. “We’re trying to get the immune system to operate at the boundaries of what it’s capable of doing. There’s the potential that your immune system could hurt you.”

Speaking Up

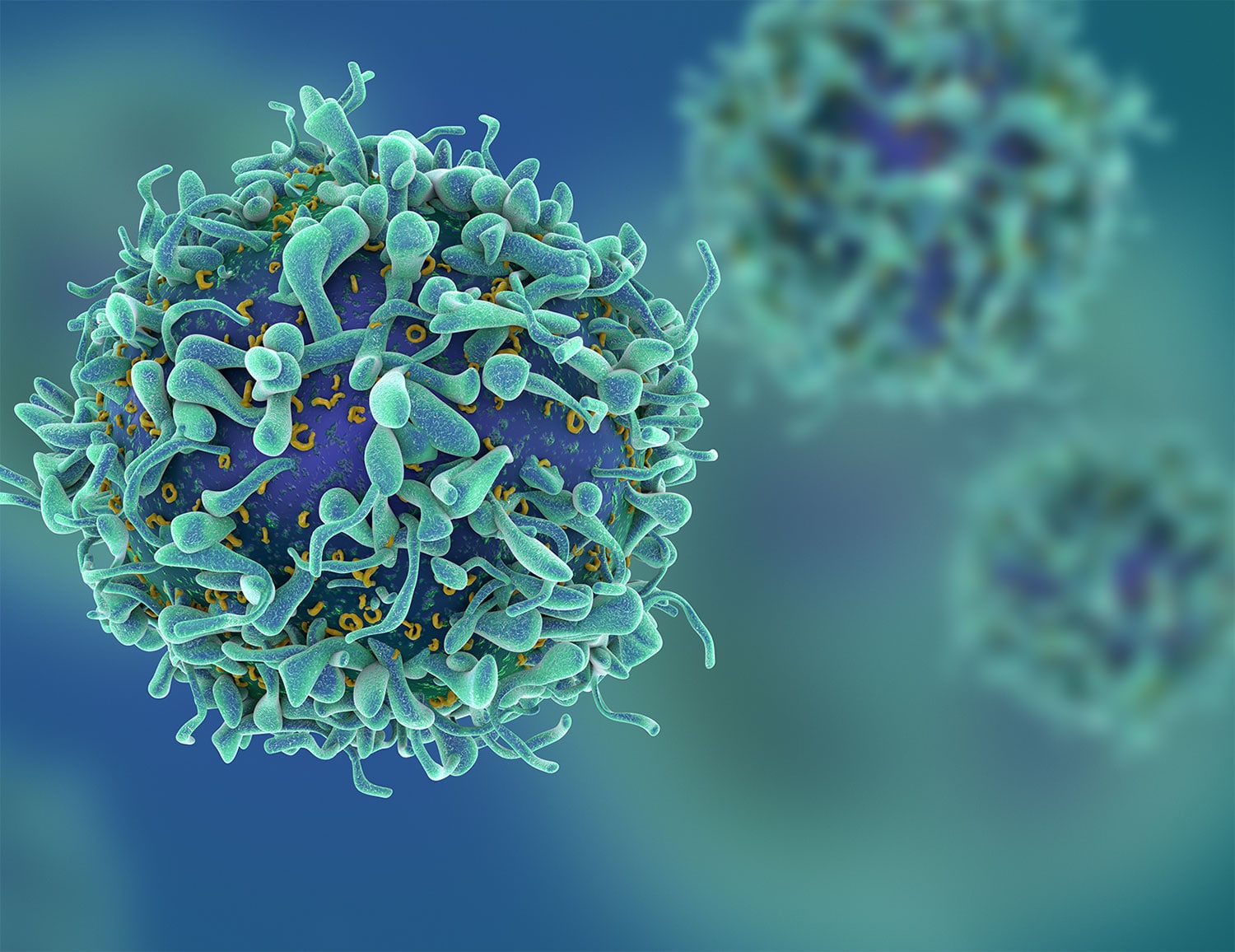

The reason checkpoint inhibitors help the immune system kill cancer is also the reason they cause side effects. Checkpoint inhibitors “disable the molecular brakes that keep our immune cells under control,” explains Wolchok.

“These medicines don’t just cut the brakes on T cells—which are a type of immune cell—that recognize cancers,” says Wolchok. “They’re doing it to all the immune cells in the body that have these brakes on them.” Immune cells that would normally exist in the blood in small numbers get “more frequent and more activated,” he explains. Some of these cells will hopefully kill cancer cells; others might attack healthy tissue.

Professional organizations have recently released guidelines for recognizing and treating checkpoint inhibitor side effects, meant to help doctors, nurses and pharmacists who may not have much experience with patients treated with immunotherapy. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer guidelines came out in November 2017, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network collaborated as each developed guidelines that were released in February 2018.

Patients also play a vital role in spotting side effects while they are still manageable. “The patient is the first line of defense,” says Julie Brahmer, a medical oncologist specializing in lung cancer and immunotherapy research at the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore, who helped lead development of the ASCO guidelines. “It’s very important that they let us know if they have side effects. It’s our job to try to read through the symptoms to figure out ‘Is this immune-related, cancer-related or something completely different?’”

Clinicians routinely monitor the blood of patients on checkpoint inhibitors, keeping tabs on the health of some organs such as the liver and thyroid. But they can’t test for every problem that might arise.

“One of the most common and potentially fatal side effects is colitis, or inflammation of the intestines,” says Wolchok. Doctors will not be aware of colitis if patients do not talk about their symptoms. “At the very beginning of treatment, I sit down with my patients and say, ‘You know what? We have to leave modesty outside. Nobody is more interested in your bathroom habits than I am.’”

Brahmer says that patients should be aware that side effects can occur even when they are no longer on a checkpoint inhibitor. The drugs themselves can remain in the body for several months after treatment ends, and the changes to the immune system can persist even longer. “It’s always something a patient has to keep in the back of their mind,” she says.

Some patients worry about telling their doctors about side effects while taking immunotherapy drugs because they fear they will be taken off a therapy that is working. But Wolchok says that a patient whose cancer is responding to a checkpoint inhibitor may have already gotten the full benefit of the drug.

Further, taking steroids like prednisone—the most common approach for treating checkpoint inhibitor side effects—does not appear to make checkpoint inhibitors significantly less effective, Wolchok says. The steroids do tamp down certain damaging immune responses, but they do not seem to impede the immunotherapy drugs from working.

A final misconception is that if patients don’t have side effects, it means their therapy isn’t working, says Jeffrey Weber, a medical oncologist at the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at NYU Langone Health in New York City. There may be some modest associations between side effects and outcomes, he adds, but it’s clear that patients with no side effects can benefit from immunotherapy and that patients with side effects do not always benefit.

Advocacy organizations track immunotherapy symptoms and offer support.

To provide support and to uncover issues that are important to patients taking immunotherapy drugs, the nonprofit organization Cancer Support Community recently launched its Immunotherapy & Me trial, which aims to test a series of immunotherapy support resources, including online courses and materials, a registry to share experiences, an app to track symptoms, distress screening, and a helpline staffed by nurses. The study will be offered at nine oncology practices around the U.S.

The Lung Cancer Registry, a project sponsored by a coalition of lung cancer organizations, also recently launched a study to better understand checkpoint inhibitor side effects. Patients can sign up to share their experiences in the registry, which asks questions about side effects, whether patients have had to delay or discontinue treatment, and quality of life.

The 1 Percent

Physicians tell patients who start on an immunotherapy to watch for specific symptoms that could be indicative of dangerous adverse reactions. But they also say that patients need to be aware of any changes in their bodies and bring them up, because immunotherapies can affect almost any organ.

For instance, less than 1 percent of patients who take checkpoint inhibitors called PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors come down with a syndrome similar to type 1 diabetes after their immune system attacks insulin-producing cells in the pancreas.

Kevan Herold, an endocrinologist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, who co-authored the first case series on this diabetes-like syndrome, says that some patients have ended up in the intensive care unit before doctors realized that their immune systems were attacking their insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Once the immune system has attacked the pancreas, the damage is permanent. Patients are treated as though they have type 1 diabetes.

Researchers are also trying to understand why a small proportion of patients on checkpoint inhibitors, likely less than 1 percent, develop myocarditis, or inflammation of the muscles of the heart. The condition can happen while taking any of the checkpoint inhibitors but is most common in patients being treated with a combination of two different checkpoint inhibitors. Myocarditis comes on suddenly near the beginning of treatment and is often fatal. To reduce this risk, some cancer centers are now routinely monitoring patients’ blood and doing electrocardiograms to look for signs of myocarditis, like elevated proteins indicating heart damage and irregular heart rhythms, near the beginning of treatment.

Javid Moslehi, director of the cardio-oncology program at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center in Nashville, Tennessee, says that it’s important to learn who is at risk for cardiac events, but he also stresses the benefits of immunotherapy. “For the first time, we have effective drugs for cancer that previously had no treatment options,” he says. “That’s really important. It should not [cause] patients not to get potentially life-saving therapies.”

To learn who is at risk for side effects, researchers are studying everything from patients’ genetics and the microbes in their guts to their medical history. Clinical trials for checkpoint inhibitors often exclude patients who already have been diagnosed with autoimmune diseases, the theory being that these patients could be more susceptible to severe side effects. But it’s not as simple as saying that people with pre-existing autoimmune diseases will get certain side effects. Recent research indicates that only some patients with diagnosed autoimmune disease have these problems, and patients without diagnosed autoimmune disease can have severe side effects.

A new type of immunotherapy, CAR-T cell therapy, comes with serious risks.

Checkpoint inhibitors are the most widely used type of immunotherapy, but 2017 saw the approval of an additional class of therapy: CAR-T cells.

To make a CAR-T cell therapy, technicians remove patients’ own T cells from their blood and then outfit them with new receptors that cause them to target specific types of cells. The two approved therapies target immune cells called B cells in the patient’s body—killing cancerous B cells along with healthy ones.

CAR-T cell therapies have led to lasting remissions in some patients with advanced disease, but they can be accompanied by unusual and severe side effects. Most patients experience cytokine release syndrome at varying levels of severity, says David Maloney, a medical oncologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle who has led multiple CAR-T cell therapy trials. Cytokine release syndrome occurs when immune signals flood the body. It can lead to low blood pressure, high fevers and general flu-like symptoms. Many cytokine release syndrome symptoms are treatable with a drug called Actemra (tocilizumab) originally approved for rheumatoid arthritis.

Some patients develop neurotoxicity, which is likely caused by disruption of the blood-brain barrier due to high levels of cytokines. This disruption can allow fluid to flow into the brain and, in some cases, lead to fatal swelling. Neurotoxicity is treated with steroids and has led to multiple deaths in clinical trials. “Hopefully we’ll learn more about what causes [neurotoxicity] to be so severe in some patients and be able to predict and/or prevent it,” Maloney says.

As with any drug, deciding to have CAR-T cell therapy is an individual choice that requires each patient to analyze possible risks and benefits, says Maloney. “You have to go into it with eyes wide open about the fact this can have severe toxicities,” he says.

While CAR-T cell therapy side effects can be severe, the therapy is used as a last option for patients. “The patients currently being treated with CAR-T cells have very few if any other options that would have any chance of getting a major response,” Maloney says.

An Emphasis on Quality of Life

It’s important to figure out how to prolong life with immunotherapy, but it’s also important to understand how therapies affect quality of life, says Karen Loss of McLean, Virginia, who was diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC in 2012 at age 53 and has had various chemotherapies, targeted therapies and the checkpoint inhibitor Opdivo.

Loss felt “good overall” while on Opdivo, aside from some mild diarrhea and a cough, but her tumors didn’t get smaller. In November 2016, she decided to go on a clinical trial of Opdivo plus an investigational targeted therapy. Her tumors shrank and then stayed stable while she was on the combination. Although she developed severe side effects, including diarrhea and vomiting, it was never clear to her whether they were related to the investigational drug, the immunotherapy or the combination of the two.

Loss stayed on the trial for 13 months, experiencing diarrhea the entire time. She loves to travel, but going anywhere proved difficult. She decided to stop participating in the trial and take a break from treatment. Her cancer remains stable.

“Having done a lot of cancer treatments over five years, I can tell you quality of life is more important to me than length of life,” she says. “You reach a point where you can say, ‘You know what? Enough is enough. I need to live the best life I can rather than the longest life I can.’”

For Long, who developed colitis after three years on immunotherapy, side effects also have meant the end of the road with her checkpoint inhibitor, at least for now. She stopped taking Opdivo and her doctors treated her colitis with steroids. In March 2018, after she had an allergic reaction to an herbal tea, she developed colitis again, perhaps because the reaction had revved up her immune system, her doctor told her.

Long currently has just one tumor, in her lung, which is much smaller than at the start of immunotherapy. She says the current plan is to stay off Opdivo unless the cancer progresses. Regardless of what happens next, Long is thankful for her experience on immunotherapy, she wrote in an email. Immunotherapy “gave me three excellent years, saw the birth of two grandkids, and many more adventures.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.