IT WAS THE SUMMER of 1959 and Jim Williams had just graduated from West Chester State Teachers College in Pennsylvania. Williams wanted to teach high school history or social studies, and maybe even coach track or cross country.

Although he had been on the honor roll, served as class treasurer, and been included in Who’s Who Among Students in American Universities, no one was hiring—or at least they weren’t hiring him. Williams was living in a country in the midst of a civil rights movement. The schools he applied to in the Philadelphia suburbs where he lived weren’t willing to hire a black man, especially one who could also be drafted into the military at any time, he says.

Retired Army colonel Jim Williams Photo by Alan Wycheck

Williams reconsidered his strategy. The U.S. military, which had been desegregated since 1948, was open to young men of all races. Knowing he was likely to be drafted anyway, Williams “volunteered” for the draft, which allowed him to choose the month he would go into the Army. He also reasoned he could overcome at least one obstacle in the way of his teaching career by fulfilling his two-year draft obligation.

After basic training, Williams was offered a spot in Officer Candidate School (OCS) and accepted it. But he soon discovered that, despite the military’s official stance on integration, attitudes about race hadn’t changed. Williams remembers his white peers marginalizing and undermining him and the only other black member of his class.

“They would throw you into these big dumpsters and bang on the container,” Williams says, remembering how black officer candidates were targeted. But one white upperclassman, Samuel Toomey III, would alert him if other officer candidates were planning to instigate a fight that could potentially get Williams kicked out of the program, he recalls. “I have these people I call angels who have made it just a little easier for me, without any grandstanding or publicity,” he says. “Sam would tell me when someone was going to try to ambush me and get me into a fight. If it weren’t for Sam, I would not have survived OCS.”

Toomey died in combat in Vietnam in 1968. Williams wore a silver memorial bracelet with his friend’s name on it for many years to remind him of everything Toomey had done to help him succeed.

Major General Edward A. Dinges congratulates Jim Williams on his 1982 promotion to colonel. Williams’ wife, Lois, stands by his side during the promotion ceremony at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Photo by Alan Wycheck

Williams also served in Vietnam. For two years, he was an infantry officer working with South Vietnamese troops. He learned Vietnamese, took classes on how to handle insurrection and made friends in the South Vietnamese infantry—friends he still talks about today. He earned a Combat Infantry Badge for his service. Of the 16 military service awards he received, he’s most proud of this one.

After returning from Vietnam, Williams held a variety of duty assignments with the Army, including as a professor of military science at Howard University in Washington, D.C. He worked his way up the ranks, retiring as a full colonel in 1984 after nearly 25 years of service. During that time, he and his wife, Lois, moved 16 times and raised three children.

In some ways, Williams, who was diagnosed with prostate cancer at age 55 in 1991, has assumed the mantle of angel, much like Toomey and the other positive influences in his life. He has made it his mission to talk to men with prostate cancer about diagnosis, treatment and life after surgery. And after seeing how many men put off doctor’s appointments and prostate exams, he is encouraging men—especially minorities—to stand up and take charge of their health before cancer ever comes into the picture.

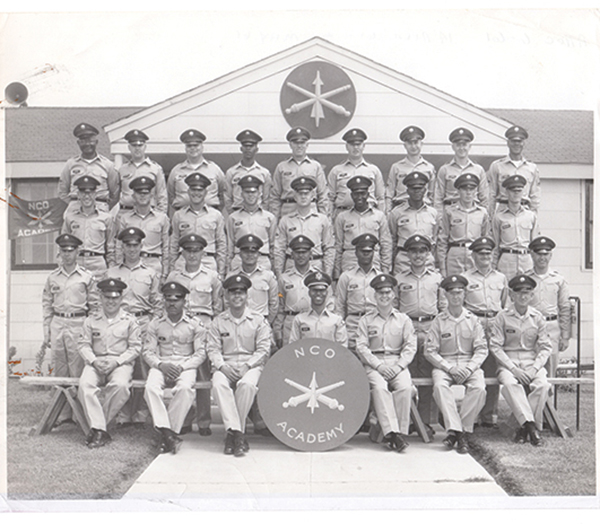

Jim Williams (center, above sign) was tactical officer for the Fort Sill Noncommissioned Officer (NCO) Academy 1961 graduating class in Oklahoma. Photo courtesy of Jim Williams

Early Detection

In 1991, after the family’s 20th move, this time to Chicago, Williams was working as a human resources director for the American Bar Association. Lois insisted it was time for her husband to see a doctor.

Williams’ physician, whose father had recently been diagnosed with prostate cancer, had begun including the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test among the normal battery of other blood tests for his patients, even though the PSA test wasn’t widely used and wouldn’t be approved as a screening tool until 1994. (The U.S. Food and Drug Administration had approved the PSA test in 1986 for monitoring men who had already been diagnosed with prostate cancer.)

Williams’ PSA numbers came back high. He went to a local urologist, who performed a biopsy and diagnosed Williams with prostate cancer. The urologist encouraged Williams to get some second opinions, including input from physicians at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota—five hours away. Williams ultimately decided to have surgery at the Mayo Clinic, since a surgeon there specialized in prostate cancer procedures.

Controversy surrounds test as a screening method.

In 1986, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test to monitor the progression of prostate cancer in patients with the disease. In 1994, the FDA approved the PSA test, in conjunction with the digital rectal exam, to screen for potential disease in healthy men. At first, the PSA screening test seemed invaluable: A quick blood draw could tell a doctor whether a patient might have the disease. The doctor could order a biopsy and determine whether the patient had cancer and needed treatment.

But the method posed problems. PSA is produced by the prostate gland in response to irritation, and that irritation could result from cancer or something else. Elevated PSA levels can also indicate noncancerous conditions, including an enlarged prostate (a condition known as benign prostatic hyperplasia) and urinary tract infections. In addition, only about 25 percent of men who have a prostate biopsy due to elevated PSA levels actually have prostate cancer.

Over the past decade, results from a number of studies suggest that many men who were being treated for prostate cancer were more likely to die with the disease than of it. In other words, men with low-grade, slow-progressing disease were having unnecessary surgeries and radiation that could result in serious side effects, including decreased sexual function and urinary incontinence.

In 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), a panel of experts that analyzes research and publishes guidelines on preventive measures, recommended against PSA screening. It was, they said, potentially causing more harm than good.

“When prostate cancer is diagnosed, in many cases, the cancer will not grow or cause symptoms, and is not life-threatening,” says Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, a general internist and epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who currently chairs the USPSTF.

The task force is analyzing data to make updates to its prostate cancer screening recommendations, which are scheduled for release in 2017. The review is timely given a May 5, 2016, letter to the editor published in the New England Journal of Medicine questioning whether PSA testing was accurately reported in a landmark study that the USPSTF used, in part, to make its 2012 recommendations against PSA screening.

Both the American Cancer Society and the American Urological Association suggest that patients ages 55 to 69 discuss PSA testing with their physicians to determine whether the screening is right for them.

On September 27, 1991, the surgeon removed Williams’ prostate and diagnosed him with aggressive stage II prostate cancer. Immediately after surgery, Williams started a six-month course of the hormone therapy Lupron (leuprolide), which suppresses the testosterone that fuels prostate cancer’s growth.

Upon returning home after surgery, Williams says he checked out a library book that discussed how to prepare for death. “This was 1991, and a diagnosis of cancer was a death sentence as far as I knew,” he says. “That was the smart thing to do. Get your stuff in order.”

Lois intervened. She had realized that, rather than planning for his death, what her husband really needed was someone to talk to—specifically, other men living with the disease. Through an advertisement in the local paper, she discovered Us TOO, a small nonprofit that offered support groups for prostate cancer survivors at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, located next to Williams’ office.

Jim Williams Photo by Alan Wycheck

“I was just out of surgery at the time and didn’t know what the future was,” Williams says. But talking openly about the disease with other men who had gone through it gave him hope. They talked about the sexual side effects of prostate cancer surgery and the potential for recurrence, and exchanged information about clinical trials and research. The support gave him a sense of life beyond prostate cancer and inspired him to begin sharing his journey with others.

As he learned more about prostate cancer, Williams noticed that men didn’t seem to attend support groups at the same rates as women and were less likely to visit their doctors to talk about their health—observations reinforced by numerous studies. He noted his African-American peers were typically absent from the support group meetings that had been so integral to his own recovery. Men also were less likely than women to fight for funding for their own gender-related health research, he says. “We’ve really not moved the bubble much in the area of men’s health. It’s still a tremendous challenge,” he says.

Williams served on Us TOO’s board for nine years, including time as secretary and six months as the volunteer executive director of the organization. He shifted gears in 2000 to focus on prevention. Today he works with a number of men’s advocacy groups at the local, state and national levels to raise men’s awareness of health issues, with a focus on prostate cancer.

In 2018, Jim Williams won the American Association for Cancer Research Distinguished Public Service Award for Exceptional Leadership in Cancer Advocacy. Watch Williams accept his award here.

As part of his work with the Pennsylvania Prostate Cancer Coalition, for example, he has spearheaded a “Don’t Fear the Finger” campaign, which underscores the importance of digital rectal exams in detecting prostate changes. The group sets up health booths at places where men often hang out, such as area minor-league baseball parks and breweries. Williams hands out blue ribbons and asks men, “How’s your prostate today?” He also works with local hospitals in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, where he currently lives, to coordinate PSA screenings so men can get blood draws to check their PSA level. If that number comes back high, the men are referred to a local urology practice, where doctors perform a digital rectal exam at no cost.

Now 79, Williams continues to travel and speak to men, encouraging them to take care of themselves and to advocate for additional funding and research dedicated to men’s health issues, with an emphasis on prostate cancer. He speaks on behalf of the Intercultural Cancer Council (ICC), a nonprofit based in Nashville that is dedicated to increasing cancer screening and improving care for racial and ethnic minorities. In addition, Williams takes at least four or five calls a month from men—friends, friends of friends, and even strangers—who have been newly diagnosed with prostate cancer and are trying to figure out their next steps.

As Williams sees it, there’s still so much left to do. “We start as patient advocates wrapped around whatever organ has hurt us. And then we find out that it’s more than that,” he says. The problem is bigger than just prostate cancer research and patient advocacy, he notes. Men, in general, are not very good at advocating for their own health—whether it’s their heart, lungs or prostate, he says.

American-born blacks are more likely to get prostate cancer than those born elsewhere.

Black men in the United States are 1.7 times more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer than white men, and are more than twice as likely to die from the disease.

But among black men who live in the U.S., the risks are further divided: Those born in the U.S. are more likely to get the disease than those born in the Caribbean, who, in turn, are more likely to get it than those born in Africa.

“By disaggregating U.S. blacks from foreign-born blacks, we can better understand [the cause] of prostate cancer based on the environmental and behavioral differences among these groups,” says Folakemi Odedina, professor and director of diversity and inclusion for the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute in Gainesville.

Several factors may contribute to the higher incidence of prostate cancer in black men, including genetic variants, poor diet and higher testosterone levels. Odedina notes that only by combing through the data will researchers be able to determine how—or even whether—genetic and environmental differences come into play.

Getting data that can help researchers identify such risk factors is a challenge. Odedina notes that just between 2 and 4 percent of those participating in clinical trials on cancer are black men, which makes it more difficult to study this population.

A Born Mediator

Williams is still a military man at heart. He and Lois live in Camp Hill in a house with a well-manicured lawn and a flagpole displaying both the U.S. flag and a Prisoners of War/Missing in Action (POW/MIA) banner. He keeps his hair close-cropped and exercises at the U.S. Navy depot in nearby Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, every day at 9 a.m.

But this disciplined man rarely raises his voice or shows his temper. “Jim was always the mediator—he was the person who kept the peace,” says Westley Sholes, a prostate cancer survivor who worked alongside Williams on the board of the ICC.

Lois Williams prompted her husband, Jim, to join a support group after his surgery and treatment for prostate cancer. Photo by Alan Wycheck

“He is the guy who starts the small talk and, inevitably, in the first three minutes, it comes up that he was in the Army, he’s a Vietnam veteran and he’s had prostate cancer,” says Kristine Warner, executive director of the Pennsylvania Prostate Cancer Coalition. And then in a short time, she adds, Williams has recruited a new board member.

Colleagues describe Williams as tireless and undeterred. “He doesn’t stop,” says ICC co-founder Armin Weinberg, a clinical professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “He continues to be engaged in these issues with the ICC and with his prostate cancer work in a way that so many people would have given up or walked away.” For example, although the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), a group of experts who issue screening guidelines, does not recommend the PSA test to screen for prostate cancer, Williams supports giving patients the chance to discuss whether PSA testing is right for them—especially African-Americans, who are disproportionately affected by the disease. He also pushes for health checks for those men who might not otherwise go to the doctor.

Williams admits that his motivation for advocacy work is a bit selfish. “Helping others helps me,” he says, contrasting it to the hardships of combat in Vietnam, where lives were lost daily. “I get a lot more satisfaction out of talking to men and helping them improve their health and save their lives,” he says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.