ED BRADLEY, A WIDELY RESPECTED JOURNALISTS best known for his work on the television newsmagazine 60 Minutes, wanted to take viewers to places they had never been and tell them about things that they had never heard. He sought assignments in war zones and regions of famine, and he brought television audiences into the living rooms of heartbroken families and beloved American entertainers.

Bradley, who spent nearly 40 years working for CBS, appreciated the power of broadcast journalism to influence public opinion and to trigger changes in policies. “You do something,” he explained during an interview for the Archive of American Television (AAT) in 2001, “because you can shine a light in a dark corner and make life better for people living there in the dark.”

However, when Bradley was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), a blood cancer, most people had no idea he was sick.

“He was a pretty personal guy. He only talked about his illness with a fairly small group of people who were regarded as really close friends,” says Norman Lloyd, now a documentary filmmaker who met Bradley on assignment in Vietnam during the 1970s and worked with him as a cameraman at CBS for several decades. “Ed was a very strong individual and he was very honest. And I think part of that honesty was to never put himself in a place of publicity or to look for attention because of his illness.”

As a correspondent for CBS, Ed Bradley covered the July 1980 Republican National Convention at Joe Louis Arena in Detroit. Photo © Associated Press

A Taste for Radio

Edward Rudolph Bradley Jr. was an only child, born to a working-class family in Philadelphia on June 22, 1941. He lived with his mother on the west side of the city and spent summers with his father in Detroit after his parents divorced when he was a young boy.

His introduction to journalism came in 1963 while he was a student at Cheyney State College, a small teachers’ college for African-American students about 30 miles west of Philadelphia. When Georgie Woods, a popular disc jockey at Philadelphia radio station WDAS, made a presentation to Bradley’s class, Bradley thanked him afterward, and Woods invited him to the studio.

“I took one look at that equipment—the turntables, the cartridge machines, the dials,” Bradley said during the AAT interview, “and I knew I’d been put on this Earth to be on the radio.” After he graduated, Bradley taught fifth grade, but he worked for free at the radio station on nights and weekends. He started by reading news summaries at the beginning of each hour, and then graduated to writing the summaries.

His first live broadcast was from a church where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was making a civil rights speech. Later, his coverage of the Philadelphia race riots (where he reported the news from a pay phone) helped him negotiate his way onto the radio station’s payroll. In an interview with AAT, Bradley recalled making somewhere from $1.25 to $1.50 an hour at the station, which wasn’t enough to allow him to quit his day job teaching.

When he read that radio station WCBS in New York City was going to an all-news format, Bradley sent a letter to the station asking for an audition. In 1967, he became the first African-American correspondent at WCBS and finally was paid enough to pursue his passion for radio full time. At first, he liked the pace of the news reports, but he eventually grew tired of churning out daily news stories.

Reduced-intensity transplants incorporate donor’s immune cells.

An allogeneic stem cell transplant, in which stem cells are extracted from a donor’s bone marrow or the bloodstream and injected into a patient, offers some chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients a chance to fight the disease. In this procedure, the donor’s healthy cells repopulate the patient’s bone marrow and kill off remaining leukemia cells.

However, a stem cell transplant can be dangerous for CLL patients, who are often diagnosed with the disease when they are older. These patients may be too frail to receive the high doses of chemotherapy, and sometimes radiation, that are required to effectively wipe out both healthy and diseased cells in the bone marrow before the transplant. Transplant patients are also at risk of developing a dangerous and life-threatening condition called graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), in which the donor’s cells attack the patient’s organs, damaging the skin, intestines and liver.

Several years before Bradley’s death, studies began to show that reduced-intensity transplants, which use less chemotherapy prior to the transplant, may be a safer and equally effective approach.

However, the reduced-intensity approach doesn’t decrease the risk of GVHD. Dan Fowler, an oncologist and senior investigator with the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., has been researching reduced-intensity transplants that add a second transplant—this time using the donor’s immune cells. His approach, which is being tested in clinical trials, extracts and purifies selected CD4+ T immune cells and cultures them so they differentiate into a powerful “booster” of T-helper cells that can be transplanted into the patient two weeks after the initial procedure. The donor’s immune cells, which recognize the stem cells as their own, help to decrease the likelihood of GVHD and may also help treat the cancer, says Fowler.

“Our hope is that with [lower risks], these transplants can be considered sooner in the treatment of CLL,” Fowler says.

To find more trials testing this approach, go to clinicaltrials.gov.

Going Overseas

After a few years with WCBS, Bradley went on his first European vacation. The three weeks he spent in Paris left him longing to return, so he saved money and moved there in 1971. He had no plans, Bradley told an interviewer, other than to soak up the history and culture of a place that was unlike any other he had previously known. Later that year, when his funds dwindled, Bradley accepted a position as a stringer with the Paris bureau of CBS Radio and got his first television assignment, which aired on Walter Cronkite’s CBS Evening News. That led to an offer to go to Vietnam for CBS Television in 1972.

Bradley’s coverage during the next two years brought viewers a disturbing view of the war and even put him in the line of fire, when, in 1973, shrapnel from a mortar blast struck his arm. After the war, Bradley was assigned to the CBS News Washington bureau, where he covered the 1976 presidential election and Jimmy Carter’s campaign and presidency, becoming the first African-American to be named White House correspondent for CBS News.

But Bradley grew restless once again. In 1978, he became the principal correspondent at CBS Reports, a documentary-style news show. He returned to Southeast Asia to interview Vietnamese refugees who were fleeing after the communist takeover of their country. As he interviewed the refugees, the camera operator began to show dozens of gaunt men, women and children struggling to reach the beach in Malaysia as the boat carrying them sank beneath the muddy waves. Bradley set aside his microphone and waded through the waist-high surf to help.

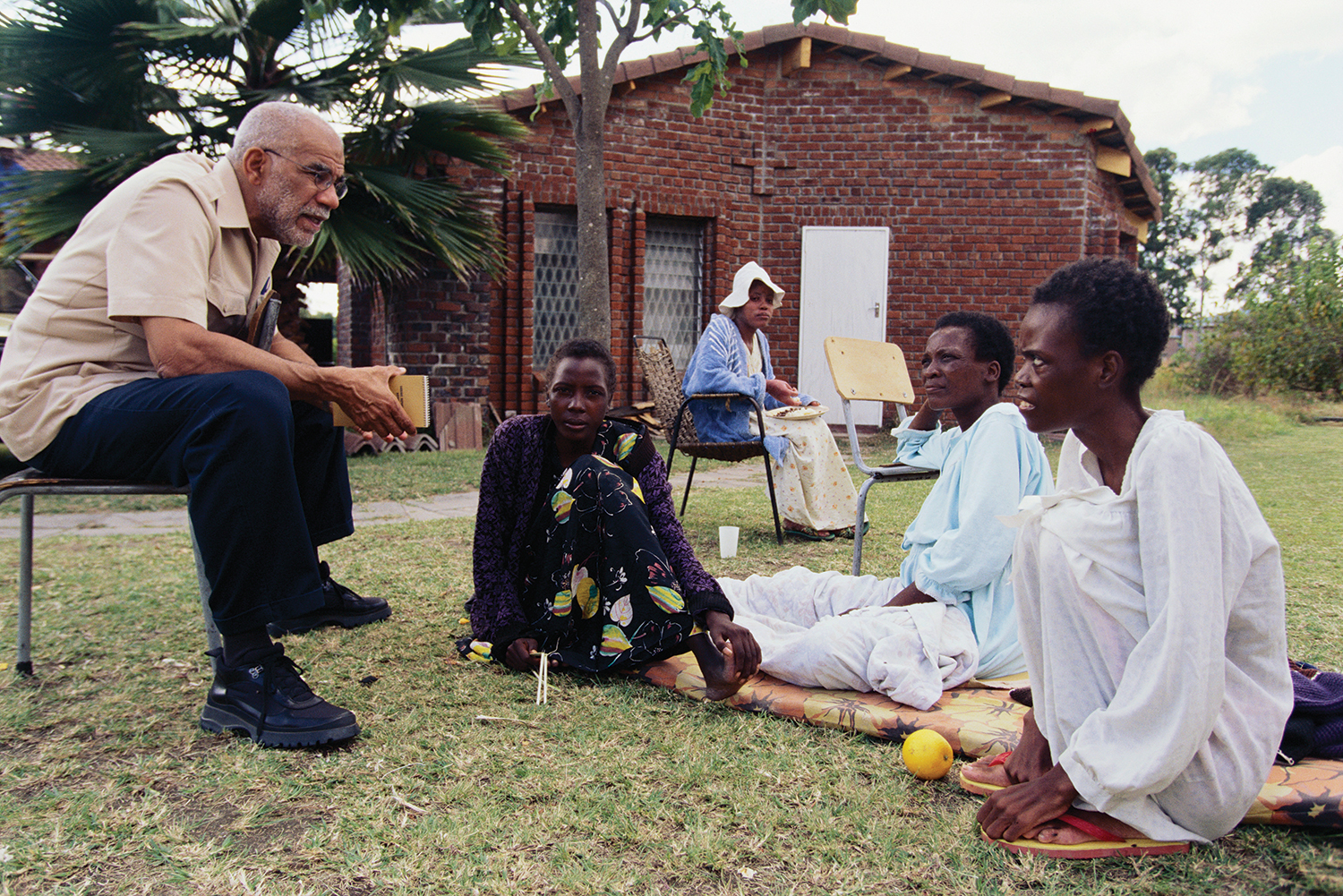

On assignment for 60 Minutes in 2000, Ed Bradley interviews AIDS patients at the Mashambanzou AIDS Hospice in Gweru, Zimbabwe. Photo © Louse Gubb / Corbis Saba

The following year, Bradley won an Emmy for the story, a portion of which was rebroadcast on 60 Minutes. In 1981, Bradley joined 60 Minutes, replacing Dan Rather, who moved to the CBS Evening News when Walter Cronkite retired.

The documentary-style reporting on 60 Minutes spoke to Bradley’s varied interests. “You can have a lot of things on your plate and they’re all different,” Bradley said of stories that he covered. “I think that’s what keeps the creative juices and the interest flowing. You’re not locked into doing the same thing all the time and becoming a One-Note Johnny.”

Bradley married three times. He had no children of his own, but people who knew him say he maintained a childlike quality, an enthusiasm for work and play, that viewers didn’t usually see on 60 Minutes. This playful side took center stage alongside professional musicians. Bradley was a jazz lover and frequent visitor to New Orleans for music festivals. He would often meet up with his good friend, Jimmy Buffett, onstage and sing backup or bang a tambourine, invoking a persona that Buffett called “Teddy Badly.”

Keeping CLL Off the Record

Although Bradley reached millions of television viewers each Sunday, he only shared the news of his diagnosis of CLL with a few close friends. Bradley’s godson, Cordell Whitlock, recalls his mother telling him about his godfather’s diagnosis around the time Bradley underwent heart surgery in 2003. “When we talked, I understood that it could be controlled and would just have to be watched, and he could still lead a normal life,” says Whitlock.

One reason Bradley may have been able to keep his CLL under wraps is the nature of the disease. In many cases, CLL advances slowly. People with the less aggressive form of CLL can often live for years with few, if any, symptoms. The disease, which is incurable, will be diagnosed in more than 15,700 Americans this year. It most commonly affects B lymphocytes, or B cells, causing them to multiply more quickly than normal and crowd out healthy blood cells in the bone marrow. As the disease progresses, patients experience anemia, bruising and a decreased ability to fight infections. When first diagnosed, many patients don’t have symptoms of CLL. They often find out they have the disease after receiving abnormal results from a routine blood test. Some signs of the disease, however, include painless swelling of the lymph nodes, weight loss and a feeling of sluggishness.

Ed Bradley, top left, spent 26 years on 60 Minutes. This 1984 cast photo includes, standing with Bradley from left, Mike Wallace and Harry Reasoner, and seated, Morley Safer and Diane Sawyer. Photo © bettmknn / Corbis

Seventy-nine percent of people with CLL live at least five years, according to the American Cancer Society. People with aggressive disease may survive only a few months, while others live for years, never seeking treatment, and die from something other than the cancer. Patients without major symptoms and with low levels of leukemia cells usually get routine blood draws to check that the levels of lymphocytes are not rapidly rising, a sign that their disease is progressing and treatment may be needed. Treatment for CLL most often involves chemotherapy but can also include radiation, steroids or, in some cases, a stem cell transplant.

Scientists are analyzing the underlying genetic mutations of CLL, which may one day lead to newer targeted drugs and treatment approaches. These mutations are already giving clues about survival. For example, 60 percent of CLL patients have a mutated IGHV gene in their B cells, which is associated with median survival of 20 to 25 years. The lack of the IGHV mutation signifies a worse prognosis, between eight and 10 years. Patients who test positive for a protein in the leukemia cells called Zap 70 have less favorable median survival rates of six to 10 years, while a negative Zap 70 is associated with median survival of more than 15 years.

“My hope has been that understanding these mutations might let us sort CLL out into different diseases, because [the cancer] really can behave very differently in patients,” says Jennifer Brown, an oncologist who leads the Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. Brown has been studying genetic aspects of the cancer in hopes of paving the way for drugs that might stop its growth.

Blocking Proteins

Since the 1980s, researchers have been studying a class of drugs known as monoclonal antibodies for CLL. These drugs fit like a lock and key on the surface of the B cell, allowing the immune system to recognize and destroy these cells. Rituxan (rituximab), which received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval as a CLL treatment in 2010, locks into the protein receptor CD20. When this drug was combined with chemotherapy in clinical trials, it extended progression-free survival from 31 to 39 months in one study and from 21 to 26 months in another when compared with chemotherapy alone.

A newer CD20 antibody inhibitor called Gazyva (obinutuzumab), approved by the FDA for treating CLL in November 2013, may do a better job of keeping the cancer in check. In a comparison of the two treatments in 657 patients with CLL, the median time it took for the disease to progress was 26 months in patients who were taking Gazyva and the chemotherapy drug Leukeran (chlorambucil), compared with 15 months in patients who were taking Rituxan and the same chemotherapy, according to a phase III trial that was published in the March 20 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Imbruvica (ibrutinib), which received accelerated approval by the FDA in February as a CLL treatment in patients whose cancer was advancing with at least one other treatment, is a targeted therapy that blocks a signaling molecule called Bruton’s tyrosine kinase that stimulates malignant B cells to grow. In a clinical trial that enrolled 48 people, more than half the participants responded at least partially to this oral drug. The duration of response ranged from five months to two years.

Whether these responses translate into overall survival benefit is not yet known. Researchers are also currently studying whether Imbruvica might increase response when given before other standard treatments, such as chemotherapy, according to Amy Johnson, a researcher at Ohio State University in Columbus, who helped develop the drug.

Making the Most of His Time

Bradley did not openly discuss whether he enrolled in a clinical trial or received any treatment for his leukemia. However, he continued to work at 60 Minutes, even as he lost weight and his health declined. A little more than a week after Bradley’s final news story aired on 60 Minutes, he died of pneumonia at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City on Nov. 9, 2006. Bradley was 65 years old.

When he started in radio in the 1960s, Bradley was one of a small number of African-American broadcast journalists. He went on to earn 20 Emmy Awards and a number of major accolades. In 2005, he accepted the National Association of Black Journalists Lifetime Achievement Award, signifying a proud accomplishment for a journalist who wanted his reporting to be judged not in light of his race, but in terms of the value it brought to society as a whole.

Bradley didn’t let his cancer diagnosis get in the way of his passion for telling engaging and honest stories. “He’d worked so hard to get where he was,” says Bradley’s godson Whitlock, who now works as a broadcast journalist in St. Louis. “He didn’t want anything slowing him down, and he certainly didn’t want any sympathy. His job was to report stories and get to the bottom of the truth, but he never wanted to be the story. That wasn’t his nature.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.