When tests showed in late 2008 that Robert Adler’s multiple myeloma needed to be treated again, his doctor prescribed the then-new anti-cancer drug Revlimid (lenalidomide). Adler was grateful he had options to treat his blood cancer. As an added bonus, this drug came in pill form, unlike the chemotherapy he had previously. Then, he got the bill.

“I got a call on New Year’s Eve from someone from the pharmacy saying something like, ‘Good news! Your insurance approved this prescription. How do you want to take care of the $3,200 you owe?’ ” says Adler, 56, from his home in Laguna Hills, Calif. “I thought they had made a mistake.” But they hadn’t. “My out-of-pocket costs for 13 cycles of Revlimid—about a year’s worth of treatments—were $41,600.”

As Adler soon learned, if he had been living in Oregon, the cost would have been similar to what he had paid when he had received intravenous chemotherapy—the direct result of an oral parity law that the Oregon legislature passed in 2007. The law requires that oral cancer medications be treated as chemotherapy given in a doctor’s office or hospital and billed as a routine visit. But in his home state of California (as was the case in every other state at the time, except Oregon) oral anti-cancer drugs are billed at the same rate as other prescription drugs—which can make their costs staggering.

“This is a loophole that leaves patients on the hook and reduces the costs insurers have to pay for these drugs,” says David Woodmansee, the associate director of state and local campaigns at the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network in Washington, D.C.

In a state with an oral parity law, according to Woodmansee, leukemia patients prescribed the oral cancer drug Gleevec (imatinib) will probably pay from $25 to $100 a month. But if these patients lived in a state without a parity law, “they may pay $1,500 to $2,000 per month.”

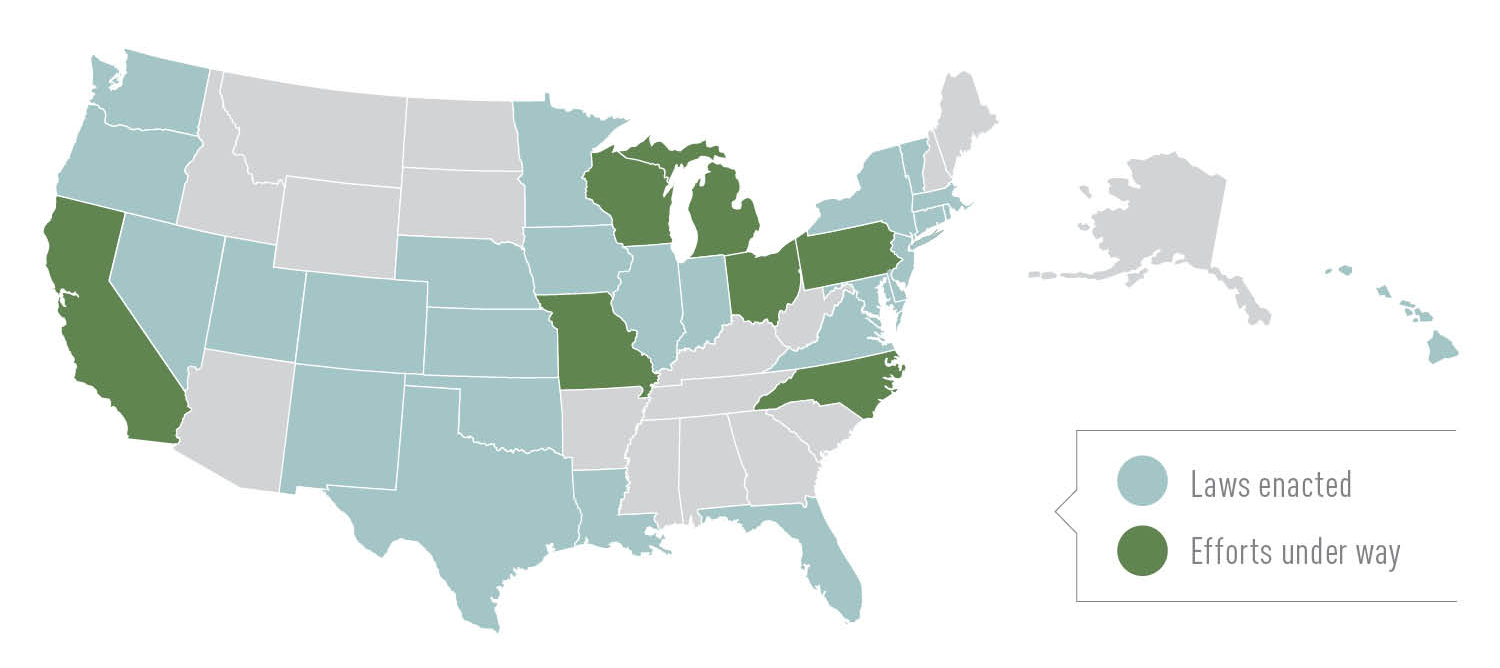

Over the past five years, cancer organizations and advocacy groups have pushed 26 states and the District of Columbia to pass oral parity laws. (These laws cover privately insured patients; they do not apply to Medicare.) Efforts are now under way in seven more states. Federal legislation has been introduced as well.

“We want insurers to … [cover] the treatment prescribed by a physician, regardless of how that treatment is administered,” says Arin Assero, the vice president of global advocacy at the North Hollywood, Calif.–based International Myeloma Foundation. “Insurance companies need to keep pace with innovation to ensure patients are getting the treatment that will give them the best chance for survival.”

Adler couldn’t agree more. “Getting a prescription for an oral medication can be like a death sentence for people who can’t afford them,” he says. “Unless you’re wealthy, cancer treatments can wipe you out.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.