Editor’s note: Cancer Today is sad to report that Bob Samuels died Nov. 18, 2012, in Tampa, Fla. He was 74. He is survived by his wife, Lillie Samuels, and sons, Robert Jr., Anthony and Christopher.

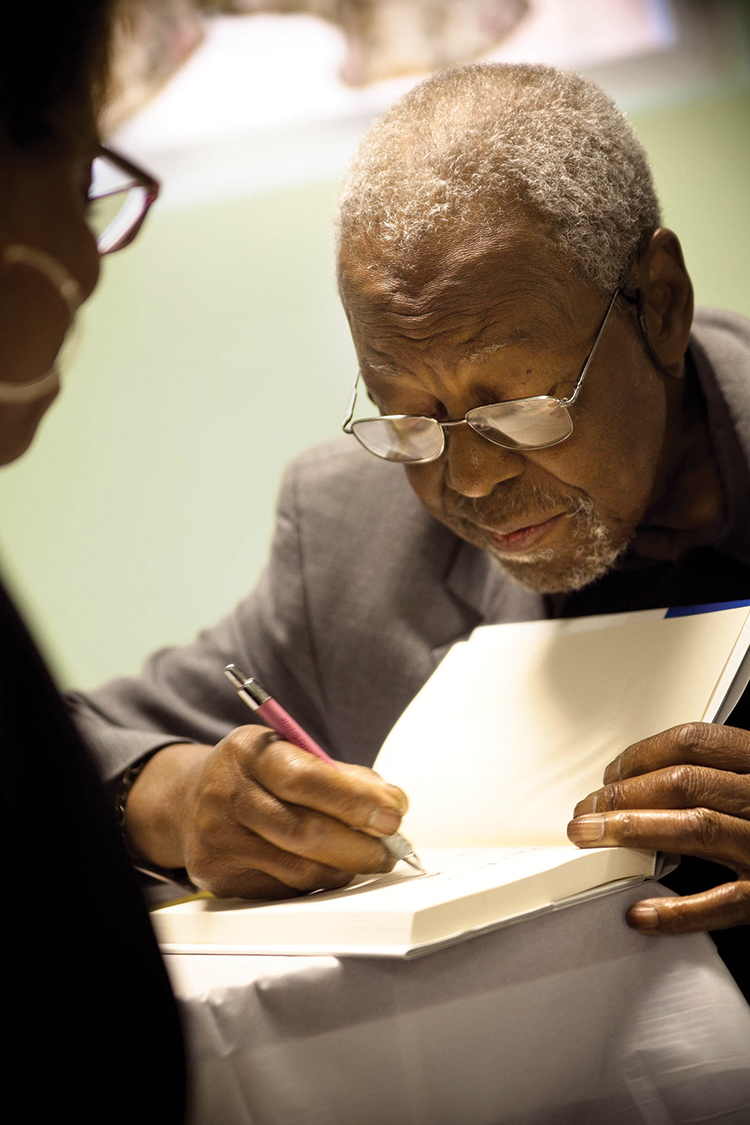

In an era of short Twitter updates, quick sound bites and hurried encounters, getting dozens of people to spend hours at a book signing is an anomaly, and a sign of the author’s impact on the world. Bob Samuels’ lifetime of service and generosity prompted just such a response: More than 60 people came to get their copies of his memoir Don’t Tell Me I Can’t signed at an event in his hometown of Philadelphia this spring.

The attendees reminisced about various periods of Samuels’ life: as a child in the Nicetown neighborhood of Philadelphia, as the first African-American bank loan officer in the city in 1964, and as a prostate cancer survivor who went on to become the founding chairman of the National Prostate Cancer Coalition.

“I thought it was going to be just a book signing,” says Samuels, 73. “But, no, it was more than that. It was catching up with people I hadn’t seen in years. It was a very, very momentous and joyous occasion.”

Dozens of people, including childhood classmates, honored Bob Samuels at a recent book signing in Philadelphia. Photo by Doug Sanford

A sign of his deep roots in the city, Samuels’ first-grade classmates from 68 years ago at St. Elizabeth’s School in North Philadelphia came to the signing. He hadn’t seen some of them in more than 50 years. They were among the first African-American boys to integrate Philadelphia’s Catholic school system in the 1940s, and many of them went on to greatness. They showed up, says Samuels’ wife, Lillie, because he “gives over and over and over again without any qualms about it.”

He’s been this way his entire life, she adds. “We ran across a lady in Philadelphia who said, ‘Bob got us organized in the first grade.’ He didn’t learn this. It’s a part of him.”

Growing up with discrimination in a segregated America, Samuels learned to overcome the low expectations of some of his teachers by witnessing the determination and strong will of his grandmother Vivian Bizzell, who worked three jobs cleaning homes to pay his $15 per week tuition at St. Elizabeth’s and keep a roof over his head. Samuels credits his education for keeping him from becoming “another statistic of the ghetto.”

“The area I was born in, the circumstances I was born in,” says Samuels, “I was so often told ‘You’ll wind up another statistic, dead or in jail by 14 or 15.’ I was determined that that was not going to happen to me, that it didn’t have to be that way, that I could show that my life had value.”

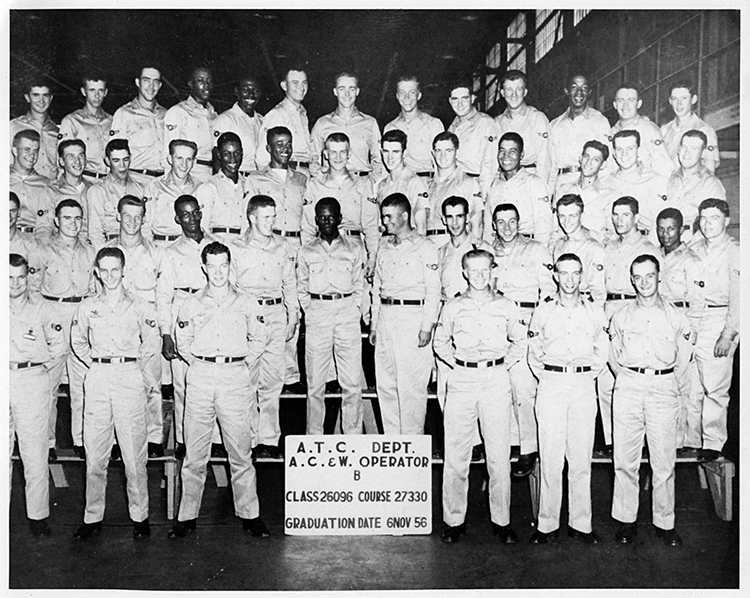

Thus began Samuels’ pattern of proving his naysayers wrong by succeeding beyond their expectations. After graduating from high school at 17, Samuels joined the U.S. Air Force, enduring weeks of name calling by white Southern drill sergeants and a posting in Mississippi in 1956, just a year after Emmett Till, a black teenager from Chicago, was lynched there. He decided he had no choice but to excel and make his family proud.

After high school, Bob Samuels (second row from top, fifth from left), joined the U.S. Air Force, enduring a posting in Mississippi in 1956, a year after black teenager Emmett Till was brutally murdered there. Photo courtesy of Bob Samuels

But after four years in the Air Force, Samuels decided to move to San Francisco to have some fun. “I was living in Haight-Ashbury with a bunch of beatniks,” he says, “enjoying wine and free love and everything else you hear about that happened there.” He might have continued with his “wild, crazy and dangerous” life in California, but on a visit to see family in Philadelphia, he nearly died in a car accident that severed his wrist and left two gashes in his head. “As I lay in the [hospital] bed … I thought I better make some productive use of this life that I have,” Samuels says. “And not knowing if I could use this arm, I said, ‘I gotta learn how to use my head.’”

Two years later, in 1962, he was working in Philadelphia as an administrative assistant at Boeing when he married Rosalind Nottingham. The next year, they had a son, Robert Jr. But his life would take another turn when, due to layoffs at the plant, he was demoted to janitor, cleaning the very office he had once occupied. He vowed then that he would “never, ever work in an industry where performance does not outweigh seniority.”

He began taking courses in finance and accounting and landed a job at Household Finance Company, where he rose to the level of senior assistant manager. He then fought to get hired at First Pennsylvania Bank, where he became the first black loan officer in Philadelphia in 1964. According to Samuels, an executive there later admitted that bank officials were apprehensive about hiring him because they worried that some white customers might become hostile if their loan applications were rejected by a black man; bank officials were also concerned about how Samuels would behave if this happened.

“I knew that if I was going to succeed,” says Samuels, “whether it was in school or in banking or in advocacy, I was going to have to work harder and be more driven than any other guy or girl.”

Photo by Cy Cyr

As successful as Samuels was in his career, he found less stability in his relationships. He and Rosalind separated in 1963, shortly after the birth of their son, and would eventually divorce. In 1969, he moved to New York City to work for Manufacturers Hanover Trust, ultimately becoming one of the bank’s first black vice presidents. A committed bachelor, Samuels spent his free time drinking, partying and dating beautiful women. He had two more children—Anthony in 1979 and Christopher in 1982—with different women.

Samuels’ biggest struggles followed his retirement from banking in 1992 at age 54. In October of that year, he moved to Tampa, Fla. After years of regimens, rules and hard work in school, the military and the banking industry, he hoped to live life on his terms. Then, in 1994, he learned over lunch that a friend had prostate cancer. The friend urged Samuels to get screened for the cancer himself.

Samuels, who learned that his prostate-specific antigen (PSA) score was sky-high, was shocked to soon receive a diagnosis of advanced prostate cancer. He was also surprised to find that African-American men are at especially high risk of developing the disease.

According to the National Cancer Institute, African-American men have the highest incidence rate for prostate cancer in the U.S. among all races, and they are more than twice as likely as white men to die of the disease. “Nobody told me that,” Samuels says. “If I had not had lunch with my friend that day, I’d probably be dead.”

Samuels was equally surprised to learn that many of his friends—of a variety of races and ethnicities—had also had the disease. He told his friends, “You guys not talking about this is going to kill the rest of us.”

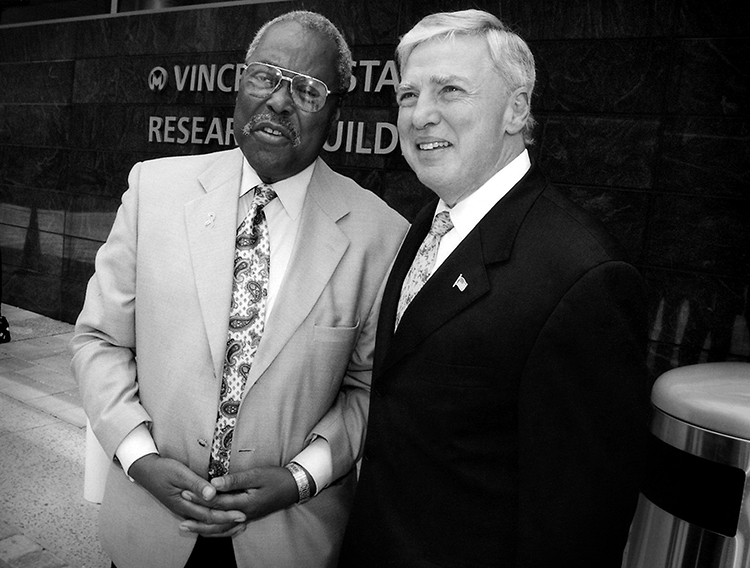

For nearly two decades, increasing prostate cancer awareness has been a mission for Bob Samuels (shown here with former National Cancer Institute Director Andrew C. von Eschenbach). Photo courtesy of Bob Samuels

That experience led Samuels to dedicate the next 18 years of his life to raising men’s awareness about prostate cancer and about the high risk of the disease among African-Americans, and encouraging men to talk to their doctors about getting screened. He is now ready to pass the mantle to a younger generation, as are many other older black men like retired Col. James E. Williams Jr., 75, a friend and colleague of Samuels in Pennsylvania who has also been leading prostate cancer awareness efforts for some 20 years.

“Unfortunately,” says Williams, “when a lot of men are diagnosed with something like prostate cancer, they say, ‘Lord, if you get me through this experience, I’ll spend the rest of my life working on this cause.’ ” And they do “for a year or two and then they’re gone. It’s hard to find people like Bob who stick with this program for many years.”

Samuels has found that for many men, one of the biggest fears related to prostate cancer treatment is that it will cause impotence—a concern he also had when he was first diagnosed. Like many men, he thought that having prostate cancer meant the sexual part of his life was over. But although he ended up being fortunate, his concerns about impotence made him aware of the importance of encouraging men to shift their perception of manhood from sexual performance. “Defining manhood is not about your sexual prowess,” he says. “It’s really about: What have I done as a human being to make life better?”

Bob Samuels’ wife, Lillie, has been his “rock” throughout his cancer treatments, he says. Photo by Cy Cyr

Lillie, who married Samuels in 1996, has been the driving force in his recovery from radiation and hormone therapy for treatment of his prostate cancer. She was also by his side when he was diagnosed and treated for throat cancer in 1999 and there again a decade later when he found out that his prostate cancer had stopped responding to hormone therapy. At that time, he joined a clinical trial of the experimental targeted drug MDV3100, an androgen receptor antagonist that is now in phase III trials. It drove his PSA levels down, but in May 2011, after Samuels began to have difficulty urinating, doctors found another tumor in his prostate—a rare small-cell carcinoma of the prostate.

That month, Samuels started chemotherapy, which “knocked me on my butt,” he says. He lost energy, was lethargic, and experienced a blockage in his bladder that required him to have nephrostomy tubes inserted in his back so he could urinate properly. He had been accustomed to exercising three hours per day three days a week. Now, he has to sit down and rest after walking one block. For the first time in his life, Samuels is slowing down.

“Even though he’s doing all he can to hang in there, I see a progressive decline,” says Lillie. “I sense him tiring out more. … And as much as he loves people and likes to go to various events, he’s pretty much stopped a lot of that. … Still, he has a desire to be with people and to enjoy life. He loves life.” So, even though he may sometimes need a nap, Samuels pushes on and is still scheduling speaking events and book signings.

That’s because, in the end, though banking gave him success, it is his work as an advocate for patients with prostate cancer that he has found most fulfilling. “In the finance and banking world, I was a pioneer,” he reflects. “In the health advocacy world, I’ve been a pioneer. Both of these worlds are part of me.” But it’s only in “the health advocacy world, I can say I’ve actually saved lives.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.