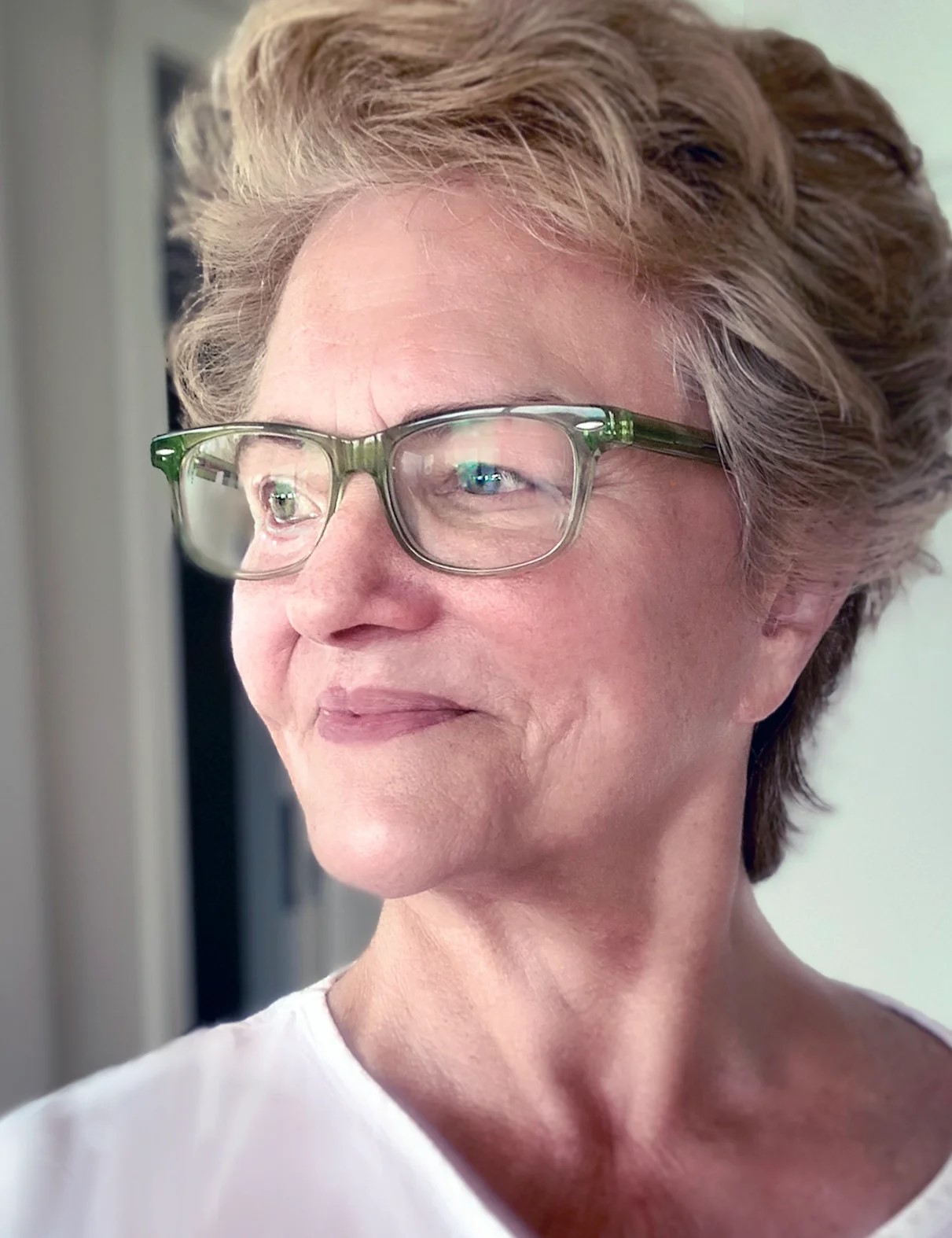

Kathleen Watt Photo courtesy of Kathleen Watt

IN 1997, AT AGE 43, New York City opera singer Kathleen Watt had become a regular performer with the Metropolitan Opera. She and the woman she loved were celebrating nearly two years of their registered domestic partnership, the closest thing to marriage for same-sex couples at the time. Then she found a bump on her right upper gumline that turned out to be the tip of a fast-growing osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer. The golf ball-sized tumor filled a chamber deep behind her right cheekbone—threatening her life and career.

In April 1997, surgeons removed the tumor along with any bones it touched—essentially half her face. Over the course of three procedures, they attempted to reconstruct the missing muscles and bones using tissue from her shoulder blade and skull, but she developed a hematoma, a pool of clotted blood that cut off blood flow to the grafted tissue, causing most of it to die. To replace the lost tissue, she received an obturator, a removable prosthetic device that replaces her teeth, her upper jaw and the roof of her mouth and allows her to speak.

Tests found cancer cells in the outer edge of the tissue that had been excised, suggesting surgery had not removed all the cancer. She had another surgery to remove additional tissue, followed by three months of chemotherapy. Within a year, her treatment was over, and the cancer has not recurred since.

But the initial surgery had damaged her right eyelids, and she couldn’t blink or produce tears. Watt had 30 procedures, including eyelid reconstructions that failed due to infection. During that time, she wore an eye patch. Doctors eventually identified the source of the infections, and she had her last eyelid surgery in February 2006. Amid the uncertainty of each procedure, she learned to take life one day at a time.

“I sort of fell in love with noticing things—things that were funny, things that entertained me, things that passed the time or gave me a laugh,” Watt says when looking back at her time in and out of the hospital. “I think of it as trying to be present with intention, and I kind of make an art of noticing. Because the calamity or the challenge that seems overwhelming and insurmountable and opaque turns out to be something that you can recognize in its parts.”

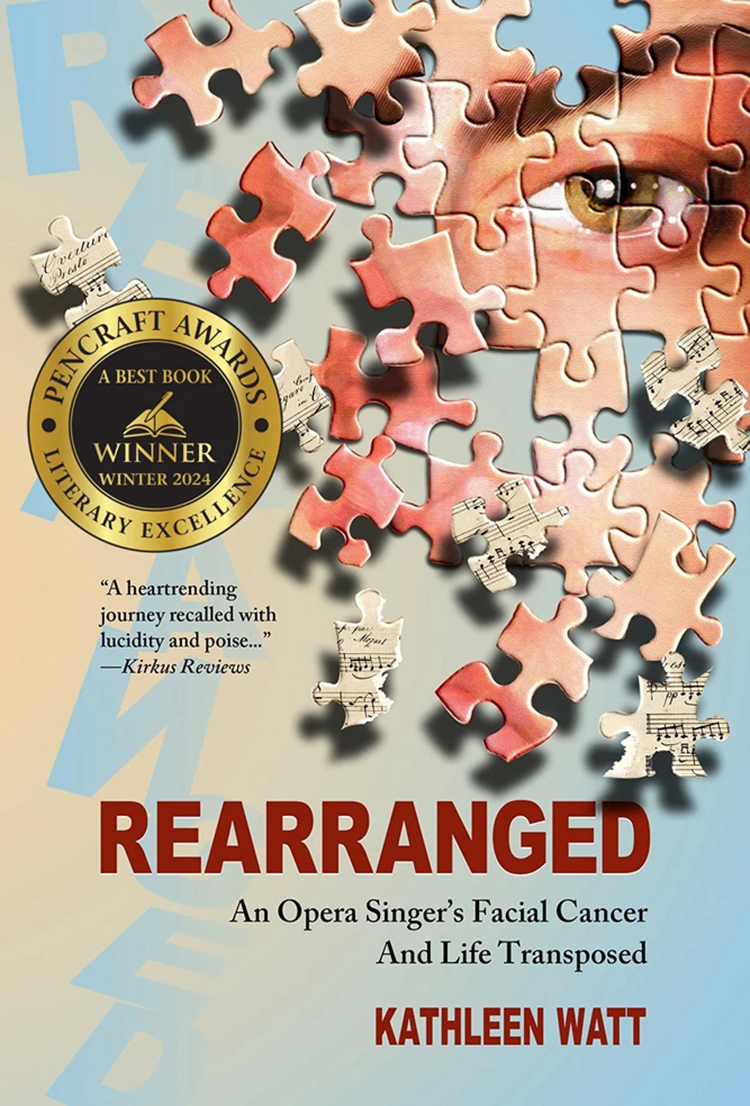

Today, Watt continues to use an obturator, and her eye is healthy, though she still can’t blink well or produce tears. While no longer a professional opera singer, Watt found a new means of expression in writing. She details her experience in her memoir, Rearranged, which tells the story of how cancer altered her appearance and her life.

Watt, who now lives outside Delhi, New York, spoke with Cancer Today about how nearly a decade of surgeries influenced her views on beauty and aging.

CT: One team of doctors suggested you go straight to having an obturator, rather than attempting a reconstruction. Looking back, do you wish that you had gone with that approach?

WATT: When I today review the facts that were available to me then, as I understood them, I do think I would have made the same decision. Doctors told me the reconstruction had at that time a 97% success rate. That my case would fall into the 3% of failures was not foreseeable.

I’ve been living successfully for almost 30 years with the prosthesis I would have had immediately following my resection if I had chosen that first. And what I lost, or what can be described as a loss, are abstract things like time, opportunity, stress on my marriage. But it’s difficult at this point to gainsay the experience and opportunities that I’ve had instead of what might have been.

CT: Did you wear the eye patch to hide your eye from view while the reconstruction was underway or to protect your eye?

WATT: At any given time, it was either or both. A big city like New York is going to have a good amount of grime in the air pretty much all the time, so I did have to shield my eye to help prevent infection. But there was also vanity involved. As long as I was only using my one good eye for vision, I could continue using a contact lens and cover the bad eye. The part of my face that was showing looked pretty much like it used to. I made up my face with my usual makeup routine.

But as I stopped wearing the eye patch, all of that changed because I couldn’t wear my contacts anymore; I had to wear glasses. My scar tissue doesn’t hold makeup, and my eyelashes were falling out. There was just no use to it anymore. At the same time, my priorities changed, and I began to feel that I just didn’t attach the same importance to those kinds of enhancements that I once did.

CT: How did your body image change throughout your experience with cancer and reconstructive surgery?

WATT: I was almost 45 when we started the process of rebuilding my face. And my surgeon said to me, “First of all, I can’t give you back what nature gave to you,” to which I replied, “Well, that’s OK; my face was going to be changing pretty soon anyway.” I basically was saying, “It can’t be worse than getting old.” It struck me as perverse that my feeling about my aging features was more or less the same way I felt about gross postsurgical disfigurement.

And honestly, as I went out in public, I preferred being able to blame the savage bone cancer rather than feeling like I had to take the blame for getting and looking older. Consequently, I felt better about myself when I looked my worst—when my face was a mashup of unfinished business—because it was clear to everyone that my flaws were not my fault.

In retrospect, I thought, “What’s wrong with me? Why is natural aging, in my mind, a fault or a flaw or something that should make me feel bad?”

CT: Once you had that realization, what changed about how you thought about your body?

WATT: As human beings, we all know the experience of putting on a mask or a costume to help us achieve the various roles that we play on a daily basis. Whether it’s an attitude we adopt, a tone of voice, or hair and makeup, we strike a pose, usually for a purpose, consciously or not. Maybe as an ex-performer, I’m more aware of how you can develop choices for which mask to put on.

But as I traveled deeper and deeper into illness as a place that I existed, I noticed that I cared less and less about any of those imposed rubrics that on a normal day you think you require. When I was sick, I looked awful every day. My hair was always weird, and then I was bald. The sicker I felt, the longer all of that went on, the less importance I personally attached to any image of beauty or rubric of hierarchy in illness or fitness or beauty or ugliness.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.