Twenty-three-year-old Milly Daniels was at a postpartum obstetric appointment in October 2005 when she mentioned the painful, fast-growing mass in her breast. The obstetrician sent her to a radiologist who, in turn, referred her to a breast surgeon.

The surgeon recommended a needle biopsy immediately. “My first reaction was ‘I can’t afford that,’” says Daniels, who had enrolled in SoonerCare, Oklahoma’s Medicaid program, when she became pregnant as a senior at the University of Oklahoma.

Medicaid.gov has information on Medicaid with links to state-specific information on eligibility standards, how to apply, and how to contact your state Medicaid office.

Ask your oncologist for help connecting with a local social worker, financial navigator or oncology patient navigator who is familiar with resources in your community.

Healthcare.gov has a searchable directory of professional brokers and community organizations who help people sign up for health insurance.

The Kaiser Family Foundation has a wealth of resources about Medicaid-related policies and their public health implications.

The surgeon assured Daniels that her staff had already confirmed her SoonerCare coverage would cover the procedure. The biopsy revealed malignant cancer cells, and three weeks later, on Feb. 13, 2006, Daniels had a bilateral mastectomy.

Pathology showed that the baseball-sized tumor hadn’t invaded Daniels’ lymph nodes. “To put it succinctly, I think Medicaid saved my life,” says Daniels, who finished treatment in 2006. “Without access to care, unfortunately, I don’t know that I would be here.”

Medicaid was signed into law in 1965 to expand access to health care nationwide as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty. As of June 2021, more than 76 million adults—nearly one in four people living in the U.S.—were enrolled in the public health insurance program.

While Medicare is funded entirely by the federal government, Medicaid is jointly funded by the federal government and each state. Broad federal guidelines mandate eligibility for certain groups, including children, pregnant people and Supplemental Security Income recipients who meet financial requirements. Each state administers its own programs, however, including federally approved, Medicaid-funded pilot programs of their own design. As a result, eligibility and coverage vary widely among states.

Since 2014, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), popularly known as Obamacare, has provided for expansion of Medicaid eligibility to include adults ages 19 to 64—even those without dependent children—whose income is 133% of the federal poverty level or lower, regardless of their assets or resources. Because 5% of income is automatically disregarded under the ACA, the effective eligibility threshold is 138% of the federal poverty level or lower.

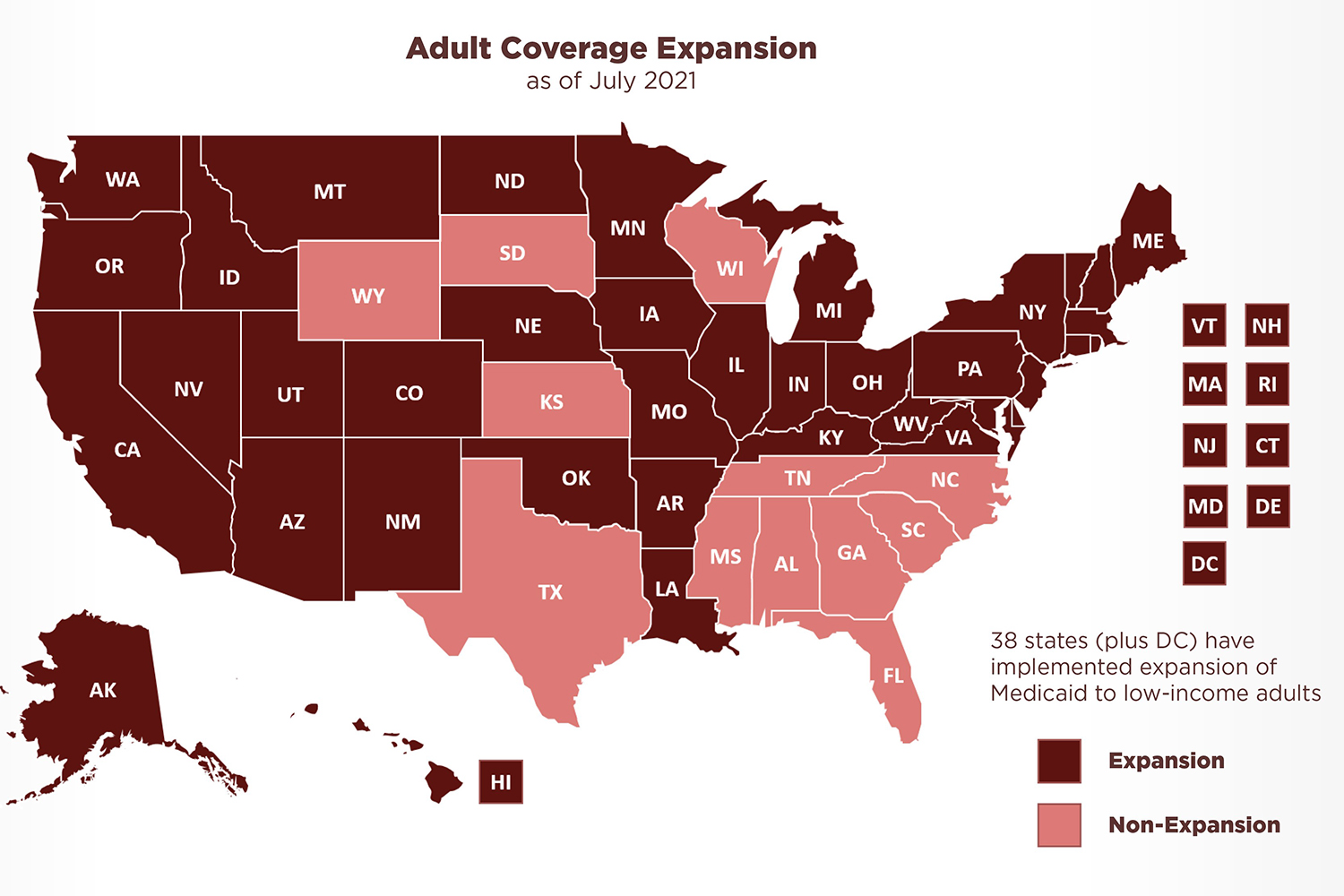

A 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling effectively gave states a choice whether to participate in that expansion. Thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia have opted in. The remaining 12 states have not. Currently voters and politicians in several of those states are weighing whether to opt into Medicaid expansion in 2022 and beyond. Meanwhile, more than 2 million residents of those states fall into an eligibility gap, unable to enroll in their state’s more restrictive Medicaid-funded program and unable to access affordable coverage through the ACA health insurance marketplace.

In the wake of pandemic-related income losses, as well as funding and policy changes related to the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, Medicaid enrollment expanded by about 12 million adults. Yet according to the U.S. census, a staggering 31 million people—many of whom were Medicaid eligible but had not applied for coverage—were without health insurance in the first half of 2021.

Sixteen years after her brush with cancer, Daniels is an Oklahoma City-based lawyer who handles personal injury and worker compensation cases. At work, she sees firsthand the financial hazards of enduring a chronic medical condition without health insurance, a fate she was spared by enrolling in Oklahoma Cares, the state’s Medicaid-funded breast and cervical cancer program. Through Oklahoma Cares, Daniels’ Medicaid coverage continued during her breast cancer treatment.

“If I had a different kind of cancer, I wouldn’t have been so lucky,” Daniels says. At that time—four years before passage of the ACA—private health insurance companies commonly excluded coverage of preexisting conditions or charged higher rates for cancer survivors. A lot has changed since then. The ACA prohibits both exclusions and price hikes for preexisting conditions, and in 2021, Oklahoma expanded Medicaid eligibility via the ACA.

Medicaid expansion saves lives, says Miranda Lam, a radiation oncologist at the Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center in Boston. On Nov. 5, 2020, JAMA Network Open published an analysis by Lam and her colleagues linking Medicaid expansion to lower mortality rates for breast, lung and colorectal cancer. “If you’re able to be diagnosed at an earlier stage of cancer, you’ll do better in terms of survival,” Lam says. “Cancer patients living in Medicaid expansion states had increased coverage, increased diagnosis at an earlier stage and improved overall survival.”

Massachusetts expanded Medicaid eligibility via the ACA in 2014; even so, Lam urges patients to seek help navigating the application process. “Insurance is tough in a lot of ways and it’s just getting more complicated,” she says.

Image courtesy of medicaid.gov

Look for the Helpers

Teri Brown works as a financial navigator for Kettering Health, a network of hospitals in western Ohio. “My whole goal is to try to save money for the patient,” Brown says.

Ohio expanded Medicaid eligibility in 2014 via the ACA, and the coverage can be the best way for some people with cancer to get the care they need, says Brown. Her team contacts new patients without insurance as soon as they are referred to Kettering’s cancer center and helps them assess their eligibility for Medicaid, Medicare and private insurance, as well as financial assistance programs administered by the hospital, pharmaceutical companies and advocacy organizations. “They’re scared to death—they don’t know how they’re going to pay for it,” she says. “I always tell them ‘Let us do this, and it’s one thing you don’t have to worry about.’”

Ohio is one of 17 states that allow certified health care providers to assess whether a person’s expected income will make them eligible for Medicaid and expedite their application through presumptive eligibility, which provides temporary coverage for immediate care while the state reviews a patient’s full application. “That’s always our goal here—to try and get these patients eligible,” Brown says. In their first conversation, she asks patients about their household size and expected income for the current month—including a spouse’s income. If the numbers work, she completes their presumptive eligibility application and helps them assemble the additional documentation required to submit their full Medicaid application.

If patients are not currently eligible for Medicaid or other health insurance, she’ll help them explore whether their income—and thus their eligibility—is likely to change. “Say they used up all their sick leave and vacation and made too much money for the month of December,” she says, “I’ll ask ‘What about January?’” As soon as a patient is likely to become financially eligible, Brown submits their presumptive application.

Brown also urges patients to tap the other safety net services available to them—including food, housing and utility assistance programs. Some patients can qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), which provides a monthly federal stipend for people with disabilities who paid Social Security taxes during their working years. The SSDI approval process can be slow, Brown says, making state- and county-administered benefits a lifeline for people who previously lived paycheck to paycheck.

As a new mom recuperating from surgery and radiation, Daniels was unable to work for four months. She tapped into food assistance programs and day care vouchers until she was able to support herself again. “I was able to claw my way out,” says Daniels. She already had a bachelor’s degree when she was diagnosed with cancer, and the physical effects of treatment didn’t compromise her ability to later earn a law degree and start her own firm. “It’s OK to be on Medicaid and not have a heroic story,” she says, “to take the resources that are there for you.”

A Package Deal

Beyond medical bills and prescriptions, Medicaid also may cover vision, dental and behavioral health care, vital resources for a person dealing with cancer. Additional coverage, including particulars of the breast and cervical cancer programs available nationwide, varies by state. “It’s worth asking, ‘What does my Medicaid cover: nutrition, transportation, mileage reimbursement?’” says patient navigator Martha Molina-Saucedo, who works for the Cancer Resource Centers of Mendocino County in northern California and provides services in both English and her native Spanish.

In rural Mendocino County, for example, taxis are few and far between. Instead, Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program, pays for a ride-hailing service for patients who need help getting to and from medical appointments—even to the University of California, San Francisco, the closest National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated comprehensive cancer center more than 100 miles away. Eligibility and coverage for non-citizens varies by immigration status and state of residence.

Ohio’s Medicaid-funded Specialized Recovery Services program provides care coordination for people with advanced cancer and has higher income thresholds than basic Medicaid. “It’s a few more steps to get it,” says Brown of Kettering Health, “but we have several patients on that.”

As with private insurance, Medicaid coverage can also vary depending on the plan a person selects, even within a single state. In California, for example, just 17% of Medi-Cal patients receive fee-for-service coverage, with the state reimbursing providers directly. The remaining 83% are enrolled in one of the state’s dozens of managed care programs. Managed care saves taxpayer dollars, but those savings can come at a cost for people with cancer, who may not have access to an NCI-designated cancer center in their network, says hematologist-oncologist Joseph Alvarnas, the vice president of government affairs at City of Hope, a cancer research and treatment center based in Duarte, near Los Angeles. “The differentiated nature of cancer diagnosis and the rapidly evolving nature of cancer treatment makes it not a health care service that’s easily commoditized,” says Alvarnas. “The cancer care expertise needed to really masterfully find a path forward isn’t ubiquitously available. Our system should account for the fact that cancer care is different.”

In 2021, the California legislature passed the nation’s first cancer patient bill of rights to protect a patient’s timely access to cancer subspecialists, clinical trials and innovative treatments, among other rights. Until such bills become the law of the land across the U.S., Alvarnas says, the burden will fall on patients to fight for their health care.

Emily Dilger of Newfield, New York, has long had Medicaid coverage, which expanded in her state via the ACA in 2014. In 2019, severe shortness of breath early in her third pregnancy led her to get an X-ray. She was diagnosed with pneumonia, and the 33-year-old was briefly hospitalized. Seven weeks later, steadily worsening symptoms led her to the local urgent care center, where she insisted that doctors take a follow-up X-ray. The image showed a 3.5-inch mass pressing against her heart and lungs. A biopsy confirmed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

“If I hadn’t advocated for myself, I don’t think I would be here,” says Dilger, who notes that the fast-growing mass had been barely a shadow in her first X-ray. “I really feel like it would have gone differently if I weren’t young, pregnant, with Medicaid.”

Even with the right diagnosis, Dilger found there were critical gaps in her coverage. Several times, her oncology practice used its financial assistance account to pay for care that her Medicaid-funded managed care wouldn’t cover. Copays for prescriptions could be too expensive for the single mother, who had to withdraw from her college coursework and cut her paid work hours during treatment. A crowdfunding campaign helped, as did members of online community groups who shared clothes for her younger children and delivered meals when she was too sick to cook for her family.

In retrospect, says Dilger, she made the best of a tough situation. “I was pretty open about my story, and I used the internet to talk about it,” she says. “People were really willing to help.”

Fifty-eight-year-old Dena Roberts lives in one of the 12 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid eligibility. The Baldwyn, Mississippi, resident is one of 2.2 million low-income people ineligible for Medicaid and without access to affordable coverage through the health insurance marketplace.

Despite having been employed since she was a teenager—as a house painter, a hotel manager and a factory worker—while raising six children, Roberts was uninsured in 2018 when she noticed pain and bleeding that she hoped was due to hemorrhoids. She put off seeing a doctor until 2021. “When you just start pouring blood when you go to the bathroom and the pain got so bad, I had to go to the doctor,” she says. “If I’d had Medicaid back in the day, I would have gotten this seen about.”

Roberts was diagnosed with colon cancer. “I was scared it might be terminal,” she says. “I was relieved to find it was stage II.” Discounted care through the local hospital’s financial assistance program partially covered the cost of Roberts’ treatment. Her adult children paid for prescriptions, and members of her daughter’s church drove her to and from radiation and chemotherapy. “If it hadn’t been for people helping me, I would have been in trouble,” she says. Even so, she finally asked her doctor to prescribe cheaper medications. “It might not have been as effective, but I didn’t care. I couldn’t pay $300 a month. It was a trying time.”

Roberts, who hasn’t been able to work since she began treatment, sees hope in the form of her pending application for Social Security Disability Insurance. In the meantime, she lives with a daughter and renews her application for hospital assistance every three months—on roughly the same schedule as follow-up appointments with her oncologist. “If it’s going to kill someone not having a doctor, let them have Medicaid,” she says. “At least let people who are really sick with cancer or heart disease or something like that have it.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.