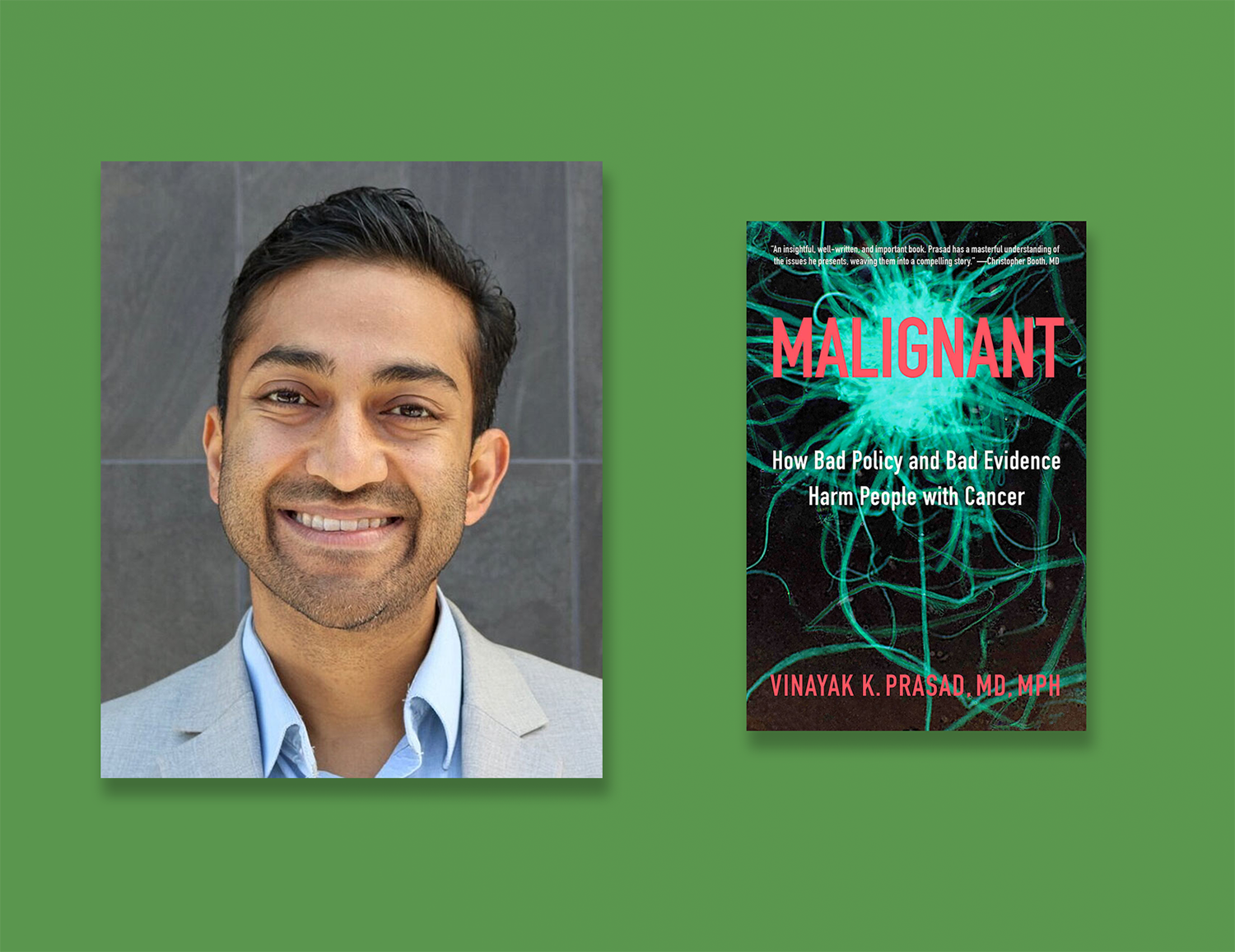

IN JUST SIX YEARS since becoming a hematologist-oncologist, Vinayak K. Prasad’s critiques of research practices and public health policy have placed him at the center of contention. The physician and cancer drug and policy researcher has earned a reputation among many scientists and amassed more than 60,000 followers on Twitter as a critic of research and health care practices.

In Malignant: How Bad Policy and Bad Evidence Harm People with Cancer, Prasad, an associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco, elaborates on his often controversial stances on issues like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug approval process, clinical trial design and the high costs of drugs.

“I think these problems are interlocked: the problem of drug costs, the standards for approval, the way many trials are run and are duplicative,” he says. “One of the reasons we don’t understand it fully is that we see each piece of it and we don’t see the whole totality, but they really depend on each other.”

Talk More About the Book

Through June 22, we will be discussing Malignant: How Bad Policy and Bad Evidence Harm People with Cancer in our online book group.

Among his appraisals, Prasad argues that clinical trials that lead to FDA drug approvals should rely on metrics that measure how long patients live rather than on measures known as surrogate endpoints. He suggests that commonly used surrogate endpoints—such as progression-free survival, a measure of the time a person lives on a drug without the cancer advancing, and response rate, the percentage of patients whose cancer shrinks or disappears after treatment—do not adequately capture the true clinical benefit of the drugs.

Prasad’s outspokenness has generated blowback from some physicians and researchers who charge that his analyses oversimplify the complexities of scientific discovery.

He recently shared some of his qualms about clinical trials and drug approvals with Cancer Today and suggested areas for reform.

CT: What is a surrogate endpoint?

PRASAD: Surrogates in oncology are measures of drug activity, such as progression-free survival or response rate, that oncologists use in practice and in clinical trials. They are not measures of drug efficacy, which is whether or not they help people live longer or better lives. I argue that drugs that shrink tumors by a certain percentage do not invariably help people live longer, and drugs that delay disease progression don’t always make patients live better. A surrogate endpoint is a value based on an assay or imaging. It doesn’t necessarily tell you when people feel good or feel bad, and it poorly correlates with living longer or living better.

CT: Are overall survival and quality of life better measures for evaluating drugs?

PRASAD: I would say those are what we care about. I think we need to routinely measure survival and quality of life, because these are the things that correlate with a true benefit for the patient.

CT: What would you say to people who suggest that using surrogate endpoints helps get more drugs into the hands of people at a faster pace?

PRASAD: Besides the fact that surrogate endpoints don’t capture what we wish they did, I think the time saved using progression-free survival in clinical trials is vastly overstated and misunderstood. If we do not require clinical trials to show benefit to overall survival and quality of life as part of the approval process, we don’t truly know the benefit of the drug for these patients.

CT: What reform do you feel would have the greatest impact on the issues you describe in your book?

PRASAD: These problems are interrelated, but if I could only make one change, I would make a change in the way the FDA approves drugs. I believe the use of surrogate endpoints for approval of drugs quickly lowers the bar on evidence. The FDA has the most regulatory flexibility to hold drug companies to higher standards.

CT: Companies are supposed to perform additional studies after drugs receive accelerated approval in order to go on to receive full approval. You write about how these studies don’t typically report back on overall survival. Can you elaborate on that point?

PRASAD: I think the paper that will best make the case was published in 2019 in JAMA Internal Medicine. Of the drugs that received the FDA’s accelerated approval between Dec. 11, 1992, and May 31, 2017, only 19 of the 93 drugs had research that showed they improved overall survival. In addition, a lot of times, these drugs are converted to full approval status based on studies that test the exact same surrogates as the ones that led to their accelerated approval, which in my mind gives no additional certainty that the drug helps you live longer or live better.

CT: What can patients learn from reading this book?

PRASAD: When we look at the history of drugs for cancer, there have always been a lot of very promising and plausible treatments we thought would work. And one thing that has given us great humility is that when many of these ideas have been tested directly in rigorous studies, they didn’t always go the way we thought. We thought more chemotherapy and stem cell transplants were going to help women with breast cancer, but it didn’t go that way, for example. We need more people to be critical and say, “Hey, we should wait for the right studies. We should do things in a more rigorous way.” I think that that’s the central tension in oncology, and I tried to talk about how all of those pieces interact to lead to the way it is now.

CT: What would be your response to patients who want more treatment options—even if the evidence isn’t up to the standards you suggest?

PRASAD: My job as a doctor is to tell the patient about the uncertainty and the pros and cons as I understand it. If someone wants to try something after that, I will generally prescribe it as long as it is in the realm of what is reasonable. Still, calling for stronger evidence benefits all patients. I think when you demand less evidence for a rare disease, for example, you are, in effect, subjecting all people with that rare disease to not have reliable information to guide their care. I think we can do better.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.