BY THE TIME AVIDEH RAMEZANIFAR was diagnosed with thyroid cancer in high school, she was already a cancer survivor.

She had been diagnosed with a germinoma brain tumor at age 12. That didn’t make the new diagnosis any easier. But it did mean she knew what it would be like to have to turn her attention away from her schoolwork and friends so she could focus on her cancer treatments.

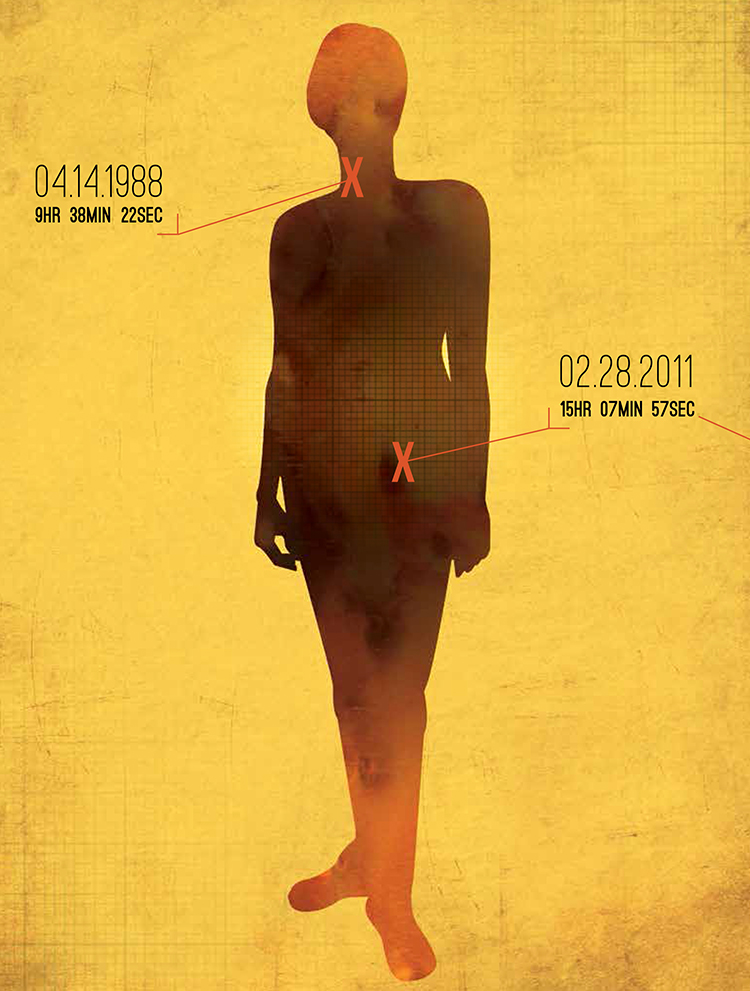

A survivor’s risk of getting a new cancer diagnosis is 14 percent greater than the risk of someone who has never had cancer.

“I’ll be honest—it was a great story for my college essays,” says Ramezanifar, of Nashville, Tenn., who’s now 21 and a junior studying chemistry at Rhodes College in Memphis.

Her story is not as uncommon as some might think. Of the 1.6 million people expected to be diagnosed with cancer this year in the U.S., about one in six will have already battled a different cancer before being dealt this new one, according to statistics from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). These aren’t patients with a recurrence—these are breast cancer survivors fighting colon cancer, or lymphoma patients discovering a tumor in their prostate.

It’s a cruel encore, like escaping the wreckage of a plane crash and then winding up on a derailed train. It’s also becoming more common: The odds of developing a new cancer are double what they were 25 years ago says Debra Friedman, a pediatric oncologist at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center in Nashville. The blame is mostly pinned on better treatments keeping survivors alive longer to run the risk of getting cancer again. Not to mention that, in general, the older you get, the greater your risk of cancer.

But a push is under way to slow down or even reverse the rising rates of second cancers—and third or fourth cancers. Doctors are changing how they give radiation to reduce the risk that it might contribute to second cancers later in life, and more emphasis is being placed on research investigating which cancer survivors are most at risk. In an indication of the topic’s increasing importance, the American Society of Clinical Oncology featured second cancers at its annual meetings in both 2011 and 2012.

It’s true that most survivors will never get a second cancer. But Friedman, who directs the REACH for Survivorship Program at Vanderbilt-Ingram, says every survivor should care about the possibility. “I wouldn’t want someone to be paralyzed by the risk of a second primary cancer,” she says. “I would want someone to be educated [about] that risk so they can learn what to do about it.”

An Interplay of Factors

The risk of a second cancer boils down to genetics and lifestyle factors—culprits behind any diagnosis—and previous cancer treatment. Sometimes doctors can assign blame to just one; in other instances all three devilishly conspire to sucker punch someone with yet another diagnosis. In general, a survivor’s risk of getting a new cancer diagnosis is 14 percent greater than the risk of someone who has never had cancer. But a person’s individual risk may be higher or lower, depending on a few things.

Some second cancers are linked to the collateral damage from powerful treatments, such as certain chemotherapy drugs, that were used to kill the disease the first time around. The risk of leukemia following chemotherapy increases within several years after treatment—and then decreases after 10 years, says Lois Travis, a physician who directs the Rubin Center for Cancer Survivorship at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York. Leukemia can also be a concern for people treated with other types of cancer drugs. For example, Revlimid (lenalidomide), a targeted drug for multiple myeloma, can triple a patient’s risk of developing leukemia or other cancers.

The effects of radiation are longer lasting: Its associated second-cancer risk remains elevated for two or three decades after treatment, Travis says, and may persist even longer.

However, most of the time previous treatments are unlikely to act alone. A 2011 study reported in the journal Lancet Oncology supports the idea that it’s an interplay of factors that influence who gets a second cancer diagnosis. Among more than 60,000 adult patients treated with radiation who developed a second cancer within 15 years of their first diagnosis, only 8 percent of cases were linked to radiation exposure. In the researchers’ judgment: Most of the second cancers were caused by factors like genetics or lifestyle.

Genetic makeup may make one person more susceptible to the ionizing effects of radiation—thereby causing a new cancer down the road—than someone else receiving identical treatment. Research also suggests certain genetic variations may predispose a person to cancer-causing effects of chemotherapy.

In addition, rare hereditary cancer syndromes, such as Lynch syndrome and hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, can increase a person’s odds of developing multiple cancers. “If someone has a genetic syndrome, they should sit down with a genetic counselor [in order to] understand their risk for a second cancer and whether that risk can be mitigated by a [preventive] surgery” or other measures like screening, Friedman says. For example, women who carry a BRCA genetic mutation, which puts them at high risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, may choose to have their breasts and ovaries removed to reduce their cancer risk.

Lifestyle comes into play, too. Some of the same factors that may have increased the risk for the first cancer—poor diet, smoking, too much alcohol, too little exercise—make a second cancer more likely, says nutrition scientist Wendy Demark-Wahnefried, the associate director for cancer prevention and control at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center.

A 2009 study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology found that obese breast cancer survivors had a 40 to 50 percent increased risk of a new cancer in the second breast compared with survivors who had a healthy weight. And people who survive cancers linked to tobacco use have one of the highest risks of second cancers, according to the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program, which collects cancer statistics across the U.S.

“We can’t dismiss the effects of treatment and genetics,” says Demark-Wahnefried. “But smoking, being overweight—those are huge in their own right.”

Develop your survivorship care plan.

When treatment ends, survivors need something tangible to navigate the road to survivorship. It’s called a survivorship care plan, or sometimes a treatment summary. And every survivor should have one, according to a 2005 report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM).

The IOM report made the survivorship care plan a new benchmark in cancer care. The plan is a personalized synopsis of your cancer treatments, your long-term risks for second cancers and other health problems, the follow-up tests you need, and the steps you can take to stay healthy.

The plans have become commonplace at large cancer centers like Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center in Nashville, Tenn. “A copy of that plan should then be shared with the patient’s primary care provider and other physicians involved in that patient’s care,” says Debra Friedman, the medical director of the REACH for Survivorship Program at Vanderbilt-Ingram.

Small cancer clinics are joining in. By 2015, a survivorship care plan must be given to every survivor treated at the more than 1,500 community hospitals accredited by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer, a consortium of professional organizations that sets standards for quality cancer care.

Don’t have a plan? These resources can help you work with your doctor to create one:

Treatment Changes

In the 1980s, doctors began fine-tuning the practice of killing tumors in ways that would help spare patients from second cancers and other treatment-related side effects. These efforts included ordering fewer chemo cycles or lower doses of certain drugs. Other changes included delivering smaller doses of radiation aimed at a more focused area of the body or using different sources of radiation that may carry less risk of inducing a second cancer. Friedman and other researchers are now at work carefully picking apart how cancer treatment, genetics and a person’s habits interact to create the perfect storm for a second cancer.

Friedman is currently analyzing data from a study in which she looked at the genes of patients treated with total body radiation before a stem cell transplant. She’s trying to figure out whether certain patients are genetically more sensitive to radiation, and what role tobacco use and sun exposure—both before and after treatment—play in who’s more likely to develop a second cancer.

Similarly, the Children’s Oncology Group, a childhood cancer research organization, is looking at how a young survivor’s genes might increase the risk of a new cancer years after treatment. A 2001 study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology suggests that one in 10 childhood cancer survivors develops a second cancer, although that risk depends on the original cancer type.

Knowing what makes a person—young or old—more likely to develop a new cancer later in life could allow doctors to tweak treatment for certain patients, Friedman says. For instance, a genetic difference might cause a patient’s body to metabolize chemotherapy very slowly, leaving the toxic chemicals in the body for too long. “We could give those patients [individualized doses of chemotherapy], decreasing their second cancer risk down the line,” Friedman says.

What You Can Do

It can be hard for a patient to focus on a conversation about cancer prevention in the midst of treatment. “You mention the risk of a second cancer at the beginning of therapy and most patients go, ‘Uh huh, uh huh,’ ” Friedman says. “They’re fighting for their lives at that moment, and their mind is somewhere else.”

Still, a discussion is needed at diagnosis about the patient’s family cancer history and possible genetic cancer risks, as well as the potential for certain treatments to increase the likelihood of second cancers later in life. It should be followed up with a second conversation post-treatment, when the patient is in a “Now what?” state of mind.

Survivors should talk to their doctors about their second-cancer risk and ask for a personalized survivorship plan that details how to reduce that risk, experts say. Many treatment centers are already initiating these conversations. For instance, at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, all survivors are told about their individual risks of developing second cancers, says medical oncologist Ann Partridge, who directs Dana-Farber’s Adult Survivorship Program. Survivors are also counseled about healthy behaviors that can lower risk and about any cancer screening they should receive.

Survivors of childhood cancers—who studies suggest may be especially susceptible to the effects of cancer treatments—should follow cancer screening guidelines developed specifically for them, says Travis. Take women treated with chest radiation for Hodgkin lymphoma at a young age. Because they now have an increased risk of breast cancer, their doctors should determine if they need annual mammograms and breast MRI scans starting at age 25, or five to 10 years after radiation exposure, the screening recommendation for cancer survivors published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology last October.

It was a follow-up CT scan in 2010 that spotted a tumor in Dale Smith’s kidney, 16 years after he was treated for testicular cancer that spread to his lungs. The second cancer had nothing to do with the first, doctors told Smith, and it would not have been found as early were he not receiving the CT scans for his testicular cancer.

“Five years into it you’re quote ‘cured,’ but I kept seeing my oncologist every three years for a check-in CT. Glad I did,” says Smith, 66, a retired communications consultant from Stewartsville, N.J., who subsequently had the tumor and part of his kidney removed.

Survivors should also take advantage of cancer screening tests recommended for their age, Partridge points out. That means a 50-year-old breast cancer survivor still needs to get her colon checked, based on American Cancer Society guidelines. “I’ve had a number of breast cancer patients go on to have colon cancer,” says Partridge. “Some of that may just be that these aren’t uncommon cancers, and people are getting older and getting them both.”

Travis says survivors of adult-onset cancers should focus on developing a healthy lifestyle—quitting smoking, not drinking too much alcohol, maintaining an ideal body weight and exercising regularly. Fortunately, the resources available to help survivors accomplish this are growing. Nonprofits such as the Cancer Support Community and survivorship programs like the one at Dana-Farber offer free exercise classes and nutrition counseling. The Livestrong Foundation offers a 12-week health and fitness program at select YMCAs in 23 states. For smokers, the NCI covers all bases at Smokefree.gov: a quit line, text messaging and a mobile app to help people break the habit.

Back in Tennessee, Ramezanifar says her goal is to go to pharmacy school and eventually to help in developing countries “however I can.” For now, cancer occupies her only a few days of the year when she undergoes a follow-up brain MRI and a whole-body scan. “My doctors say I’m prone to having cancer again when I’m older since I had cancer treatments at such a young age,” she says. “I’ll be ready for it.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.