William G. Nelson, MD, PhD Photo by Joe Rubino

RADIATION HAS LONG BEEN an essential tool in managing life-threatening cancers. Cancer cells exposed to sufficient doses of ionizing radiation can be killed.

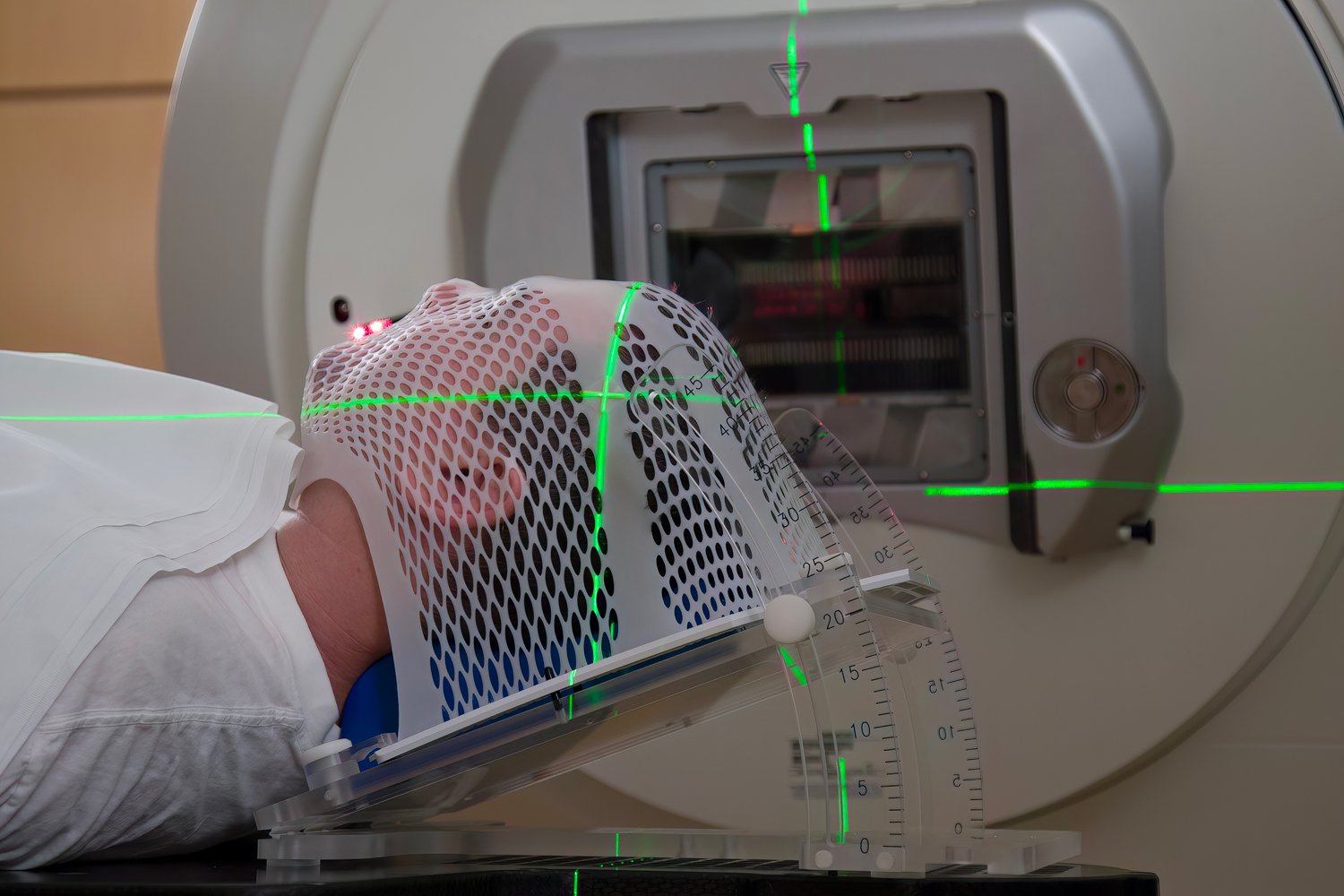

The key clinical objective is to deliver lethal amounts of radiation to cancer cells while minimizing injury to nearby normal cells and tissues. To do so, the total dose is administered in small increments (fractions) daily over four to five weeks. This approach limits both short- and long-term toxicities and complications, though catastrophic late effects can still occur. For example, some 8% of adults treated with radiation therapy develop second cancers within 15 years of treatment.

Modern radiation therapy machines can deliver photons (high-energy X-rays), electrons or protons to cancer deposits anywhere in the body. Anticancer activity and normal tissue toxicity can be influenced by the type of radiation used, the total dose delivered, the dose rate (how much radiation per second in a single treatment fraction), and the fractionation scheme (how much radiation each day and for how many days). With the number of radiation-treated cancer survivors in the U.S. projected to reach 4.17 million by 2030, most of them treated for breast or prostate cancer, radiation oncologists are exploring new ways to improve cancer control while reducing damage to normal tissue.

The unit of absorbed radiation dose is the gray (Gy). For a typical course of conventionally fractionated photon radiation therapy, 1.5 to 2 Gy are delivered each day for several weeks to reach a total of 50 to 80 Gy. More recently, advances in technology have led to more accurate shaping of radiation beams to deposit the dose into more precise volumes. This has allowed radiation oncologists to use hypofractionation, which delivers an increased daily dose (as much as 2.4 to 3.4 Gy per day) over a shorter period of time, resulting in a total dose slightly lower than the amount for conventional radiation. The hope is that hypofractionated radiation might be more effective in killing cancer cells without damaging normal cells in the treatment area.

Clinical trials conducted for breast and prostate cancer patients have suggested that hypofractionated radiation performs at least as well as conventionally fractionated treatment, with equivalent cancer control and similar short-term side effects. This has emboldened radiation oncologists to deliver very high dose fractions (7 to 9 Gy or more) using an approach termed stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). For localized prostate cancer, SBRT to a total dose of 36.25 Gy given in five treatment fractions over one to two weeks was found to be as effective as conventionally fractionated (78 Gy in 39 fractions over 7.5 weeks) or moderately hypofractionated (62 Gy in 20 fractions over four weeks) radiation for treatment, though SBRT was slightly more toxic than the other methods.

The success of hypofractionated radiation treatment schedules for breast, prostate and other cancers has begun to transform radiation oncology. With hypofractionated radiotherapy, patients can complete treatment courses in shorter times with fewer visits, limiting the need for travel to and from radiation treatment centers. The shorter treatment courses are also associated with lower costs and more treatment capacity to benefit patients.

Where is this fine-tuning of radiation treatment headed? The latest tactic is to increase the rate at which a radiation fraction is administered. The dose rate for conventional radiation fractions is around 0.5 to 5 Gy per minute, so it takes a few minutes to deliver a typical 2-Gy fraction. Preclinical model studies suggest delivering the dose at a much higher rate, such as 40 Gy per second, for just milliseconds might reduce normal tissue injury while maintaining cancer control. One explanation is that this tactic, termed FLASH radiation, might deplete the oxygen in normal cells more than in cancer cells, sparing normal cells but not cancer cells from injury and death. Another idea is that rapid exposure limits the impact on blood and immune cells circulating through the area to be radiated.

To determine whether FLASH radiation will significantly improve cancer treatment, some technical refinements to radiation equipment are required and careful clinical trials are needed. In the first prospective clinical trial of the FLASH approach, using a single 8-Gy fraction of electron radiation therapy given at an ultrafast dose rate, 12 painful bone metastases were treated in 10 patients. The treatment alleviated patient discomfort in two-thirds of the lesions. Promising results indeed, but more work is needed to ensure that this new approach is more than a FLASH in the pan.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.