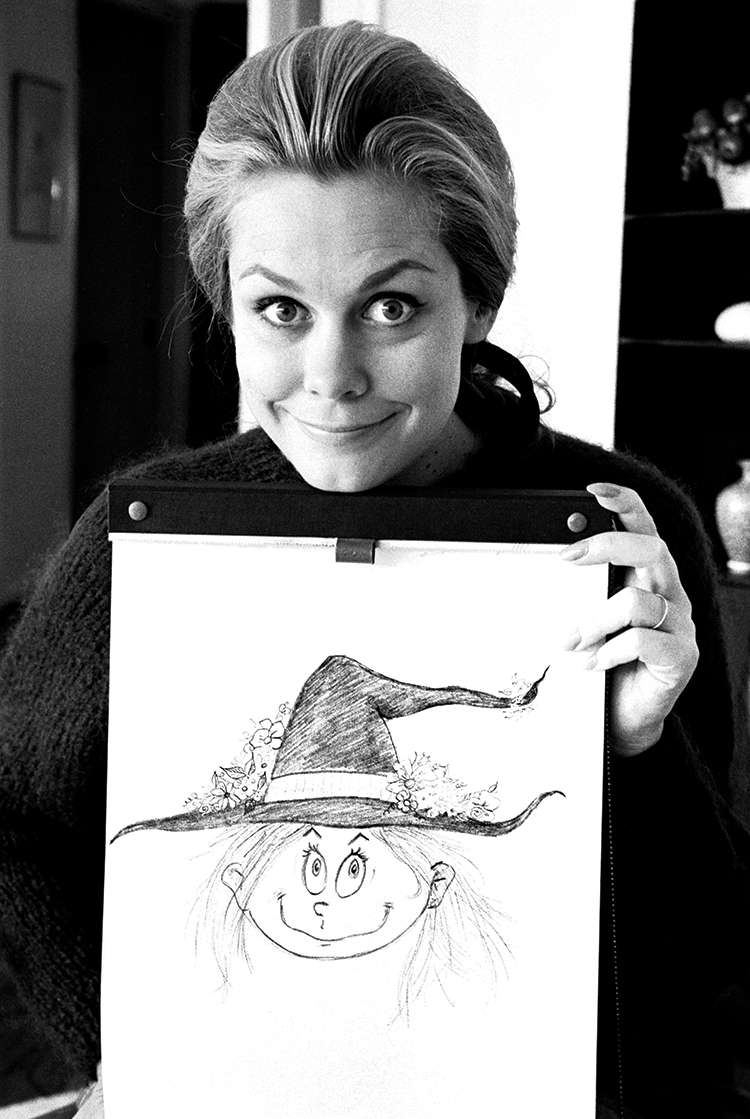

Photo by Robert Lerner / Getty Images

Decades before the name Harry Potter became a household word, it was Samantha, the beautiful wife on the television comedy Bewitched, who introduced witchcraft into the lives of ordinary muggles. With a twitch of her nose, Samantha, played by Elizabeth Montgomery, brought an alluring blend of confusion and havoc to her marriage to nonmagical Darrin Stephens, and their spirited suburban relationship—complete with a meddling witch/mother-in-law—quickly became the No. 2 show in America (behind Bonanza) when it debuted in 1964.

Making Cancer Screening Easier

Nearly five decades later, it is the role of Samantha that remains Montgomery’s most indelible. But throughout her career, Montgomery’s acting acumen and her desire to defy typecasting led her to seek out many other challenging roles. This work resulted in a series of Emmy Award nominations: one for her leading role in the 1974 made-for-television movie A Case of Rape; one for her portrayal in 1975 of the 19th century accused murderess at the center of The Legend of Lizzie Borden; and, three years later, another for her depiction of a female pioneer making a home in the Ohio River Valley in the TV miniseries The Awakening Land. (She also received nominations every year from 1966 to 1970 for her role on Bewitched.)

Montgomery was determined to go beyond her beauty and background to make a name for herself, on her own terms. Never a diva, she was unfailingly polite to her co-workers, and to her fans she was pert perfection. To her family members and close friends, she was known for her desire to shield her personal life from the public eye, and for a stubborn streak that few could defy. Both were visible when she learned in March 1995 that she had stage IV colorectal cancer. She was 62, and less than two months would pass between her diagnosis and her death.

A program pairs patients with screening navigators.

On paper, colonoscopy may be the best colorectal cancer screening test. But in the real world, says Heather M. Brandt, a social and behavioral scientist at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, the procedure’s bowel prep, cost and time keep many people from getting one. And that’s more true in communities that are medically underserved than anywhere else.

Brandt and her colleagues at the university’s Center for Colon Cancer Research recently joined other major organizations to launch a program that pairs patients in these communities with “screening navigators.” These professionals guide patients step-by-step through the entire process of getting a colonoscopy—from scheduling an appointment to learning about the kinds of follow-up they may need. Patients pay nothing for their colonoscopies or the navigation service.

Since the program was launched in November 2011, Renay Caldwell, a screening navigator in the Columbia area, has already helped more than 40 people obtain a colonoscopy. Caldwell greets each new client with water, a granola bar and palpable enthusiasm. “I tell them, ‘I’m your personal tour guide and my job is to make sure you have a good experience. Your job is to arrive [at your colonoscopy] well-prepped so that you have a good experience and so that you can tell others in your community that this is something they need to get done.’ ”

The navigation program recruits patients from four free clinics that cover dozens of counties in South Carolina. None of Caldwell’s patients has a household income more than 25 percent above the state’s poverty line, and most have never had someone provide this type of personalized medical care.

Caldwell uses videos, pictures, written materials and humor to explain the benefits of colorectal cancer screening, how a colonoscopy is performed, and proper bowel preparation. Her success rate is high: Only two of her patients have not shown up for their colonoscopies. What’s more, a number have already referred friends and family members to her. “This is not only navigation,” she says, “it’s educating a community.”

Born to Act

Montgomery was born in 1933 in Los Angeles. Her father was actor and director Robert Montgomery, who, in 1935, became the president of the Screen Actors Guild. Her mother was Elizabeth Bryan Allen, a socialite who performed a handful of times on the New York stage in the 1920s. The couple moved to California in 1929, when Robert signed a contract with MGM studios. In 1950, when Elizabeth was 17, a new job opportunity for her father led the family to return to New York City.

There, Montgomery attended the Spence School, one of the city’s most exclusive all-girls schools, and then the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. Her acting debut occurred in 1951, at age 18, on her father’s television show Robert Montgomery Presents, which aired live from a studio in Rockefeller Center. Four years later, she appeared in her first film, The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell. Over the next decade, she performed in episodes of many popular series, including Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone and The Untouchables.

Montgomery’s first marriage, to socialite Frederic Gallatin Cammann, lasted less than a year. Her second, to actor Gig Young, lasted a little more than six years. In October 1963, Montgomery married writer-director-producer William Asher, whom she met when she auditioned for the lead role in his movie Johnny Cool. The following year, they worked together to develop the series Bewitched. Their first son, William Asher Jr., was born shortly before Bewitched premiered in 1964.

Montgomery’s next two pregnancies were written into the script, and were the catalysts for the show’s addition of the Stephens’ children, Tabitha and Adam. Bewitched ended its eight-year run in 1972, and in 1973, she and Asher divorced. She then entered a relationship with actor Robert Foxworth. They had been together nearly two decades when they married in January 1993, a little more than two years before her death.

Photo courtesy of mptvimages.com

Private, But Not Shy

Having been raised with an insider’s knowledge of Hollywood glamour and New York nightlife, Montgomery knew how to carve a life among the stars. “There was a big sort of kind of paradox between her public self and her private self,” says Foxworth. “She was gorgeous and sexy and funny and witty, and in public she loved to dress up and go out. And on the other hand, she loved to dig in the garden and get her fingers dirty and make things grow or get a paintbrush and paint things. She was a lot of fun and she could dance like a demon. But what she most loved was her work—she loved being an actress.”

Montgomery developed a political side as well. Her father, an active member of the Republican Party, had appeared as a friendly witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947, and he later served as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s television coach during his run for the presidency. “At some point,” says Foxworth, “she realized that her father had been very political … and she was kind of motivated to oppose him.”

It was no accident that Montgomery decided to play a rape survivor treated horribly by the criminal justice system in A Case of Rape. “She felt it was important,” says Foxworth, “and she was proud that it contributed to the legislation” that most states implemented in the late 1970s to expand the ability of prosecutors to bring rape cases to trial.

In 1988, she was quick to sign on when a friend asked if she would be interested in narrating the documentary Coverup: Behind the Iran Contra Affair. “She read the script and she just called us right up … and said she’d love to do it,” says Barbara Trent, the film’s producer. Four years later, in 1992, Montgomery teamed up with Trent again to narrate The Panama Deception, which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary.

“She was so sweet,” recalls Trent. “Our sound studio was so small [that] once we closed the door to have silence, there was no air conditioning and we were dripping [with sweat]. But she was always perfectly composed. And she would do a take as many times as she was asked. She told us the greatest joy was when she looked up and [we told her] the recording was perfect—and we were nobodies. … I have no reason to believe that we would have won the Oscar without her.

“She was the perfect person to narrate the film,” Trent adds, “because she was so un-political in her public life. There was no one who had a negative political opinion of her, which was ideal.”

Photo courtesy of Screen Gems / Getty Images

Off the Radar

When Montgomery died in May 1995, colorectal cancer was the second leading cause of U.S. cancer deaths, as it is today. But the idea of colorectal cancer screening wasn’t on most people’s radar. In fact, it wasn’t until December 1995 that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force for the first time, acting on evidence from recent studies, recommended that primary care physicians have their asymptomatic patients over 50 routinely screened for colorectal cancer, by either a fecal occult blood test or flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Over the next few years, colonoscopy also began to be more widely recommended for screening, due to its ability to both detect cancer early as well as prevent it through the removal of precancerous polyps. The procedure received a boost in March 2000, when news anchor Katie Couric focused attention on the importance of colorectal cancer screening by undergoing a colonoscopy on NBC’s Today show, which she co-hosted at the time. (Her husband had died of the disease in 1998 at age 42.) The following year, access to the procedure increased dramatically when Medicare agreed to cover routine colonoscopy screening. “That was a game-changer,” says Heather M. Brandt, a social and behavioral scientist at the University of South Carolina, in Columbia.

Due to increased screening, colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in the U.S. have decreased over the past decade. But more work remains. The most recent data indicate that about 40 percent of U.S. adults are still not receiving appropriate screening. And not all groups are benefitting equally from these prevention efforts. It’s important to note, says Brandt, that “we have not seen the same declines in African-Americans that we’ve seen in European Americans, and that among Hispanics we don’t see the same reductions either.” For the most part, she says, this is not due to race or ethnicity but to social problems such as access to health care.

A Changing Time

If the screening recommendations we have today were in place in the 1980s, it is quite possible that Montgomery would have had her first colorectal cancer screening test at age 50, and that her cancer would have been caught early and had a better chance of being cured, or maybe even prevented.

Foxworth believes she might have held the cancer at bay longer if she had contacted her doctor when she first began to experience pain and other symptoms. But that wasn’t the choice she made. “Hers was one of avoidance basically, and denial,” says Foxworth, who can still recall how shocked he was at how she looked after she had completed her last movie, Deadline for Murder. “I immediately told her, ‘Something is wrong.’ She said, ‘I’m all right.’ But within the next week her doctor took her to a specialist, and that’s when the diagnosis was made.” It was a Saturday, and the surgery was scheduled for Wednesday. But it was too late: The cancer had already spread to her liver and lungs, and then, he says, “Things went from bad to worse.”

The treatments that are available today also might have allowed Montgomery to live longer. “We have better diagnostic imaging procedures, better chemotherapy, effective targeted therapy, and pharmacology and pharmacokinetics—as well as molecular profiling of tumors—to help us understand how to combine various therapies and [determine] which therapies might be most beneficial for the individual patient,” explains Edith Mitchell, a medical oncologist at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

Today, Mitchell says, “approximately 20 percent of patients diagnosed with colon and rectal cancers already have metastases to other organs such as the liver or lungs at the time of their diagnoses,” which has made “multidisciplinary care, which can include collaboration with surgeons who specialize in liver, lung or other areas,” standard. It’s also now common to combine therapies, she says, “using chemotherapy and targeted therapies to shrink tumors in organs like the lung and liver … which can make surgery to remove those tumors possible.”

There is no one standard of care, Mitchell notes. “We take a personalized approach,” she says, “and [Montgomery’s] tumor would have been tested to see if it had a KRAS genetic mutation or other molecular features that would point to which therapy is likely to be most effective.”

Her Memory Lives On

Montgomery died on May 18, 1995, at age 62, at her home in Beverly Hills, with Foxworth and her three children by her side. But her memory and her performances live on: immortalized on websites devoted to her and Bewitched, on YouTube and Netflix, and in Lappin Park in Salem, Mass.—the site of the 1692 witch trials—where, in 2005, the TV Land cable network erected a 9-foot bronze statue to honor Samantha, Montgomery’s most famous role.

“Wherever I have gone—during the time she was alive and since she died—and run into people she worked with, they all talked about how much they loved working with her,” says Foxworth. “She was not a Hollywood quote-unquote snooty, egomaniacal leading lady. She was an inspiration to everyone she worked with. She was one of those people you thought would never die.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.