The summer of 1974 was one of the most tumultuous times in United States history. As the world watched in shock, on Aug. 9, Richard Nixon, battered by the Watergate scandal, resigned as president, transferring executive power to Vice President Gerald Ford. Thirty minutes later, Ford was sworn into office by Chief Justice Warren Burger in the East Room of the White House with his wife, Betty, by his side.

As the new first lady, Betty Ford quickly revealed her independent streak. Less than a month after her husband’s swearing-in, she held the first press conference given by a first lady since Mamie Eisenhower gave one in 1953, and she reiterated her support of abortion rights, a position opposed to that of her husband. As John Robert Greene wrote in his biography of Betty Ford, the White House soon discovered “the first lady would, when put in front of a camera, speak her mind.”

A few weeks later, Ford demonstrated yet again how personal politics could be. She was accompanying a friend who had made an appointment for a breast exam, and her friend encouraged Ford to have an exam as well. The doctor found a marble-sized lump in her right breast. Two days later, her surgeons performed a radical mastectomy, removing her entire breast as well as her pectoral muscles and the lymph nodes under her right arm.

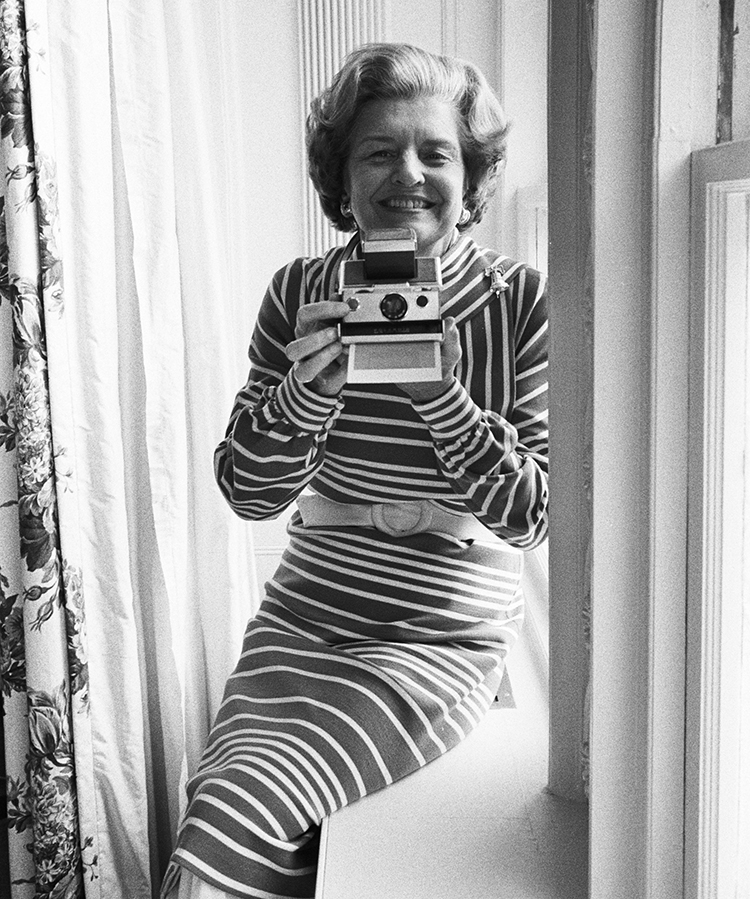

Betty Ford’s candor helped bring discussion of breast cancer into the public sphere. Photo by David Hume Kennerly / Getty Images

As first lady, Ford was expected to be visible and travel with the president, but the long recovery her radical mastectomy required could have kept her out of the public eye—which the press would have quickly noticed. She could have downplayed her diagnosis, perhaps issuing a few press releases that alluded to an illness, and no more. Instead, Ford stepped into the spotlight. She gave interviews to the media and allowed photos to be taken of her in the hospital. And the news media ran with the story.

At the time, discussing any cancer—especially breast cancer—was taboo. “In obituaries prior to the 1950s and 1960s, women who died from breast cancer were often listed as dying from ‘a prolonged disease’ or ‘a woman’s disease,’ ” says Tasha Dubriwny, an assistant professor of communication and women’s and gender studies at Texas A&M University, in College Station. “Breast cancer wasn’t even named as the onus.”

Ford’s candor brought breast cancer into the public sphere. After her diagnosis and treatment, the number of women getting breast exams increased dramatically, as did the number of women willing to talk about their own diagnoses. The silence around the disease had ended—thanks in large part to Ford.

An Auspicious Start

Betty Ford was born Elizabeth Ann Bloomer on April 8, 1918, in Chicago; two years later, her family moved to Grand Rapids, Mich. Her father, a traveling salesman for a company that sold rubber conveyor belts to factories, did well, allowing the family to become prosperous and socially connected. Betty, an energetic, self-described tomboy, had no problem mixing it up with her two older brothers.

Betty’s mother, Hortense, enrolled her in dance lessons at age 8, and she soon fell in love with the art. After graduating from high school, she attended the Bennington School of Dance in Vermont, where she came under the tutelage of the pioneering choreographer Martha Graham. “I worshipped her as a goddess,” Ford wrote in her 1978 memoir, The Times of My Life.

After a second summer at Bennington, Betty moved to New York City, where she joined the Martha Graham Dance Company and was signed by a modeling agency. She studied with Graham for three years but ultimately did not get chosen for the troupe’s traveling company. Hortense, who disapproved of Betty’s pursuit of a career in dance, encouraged her daughter to return to Grand Rapids.

Back home, Betty took a job at a local department store as a fashion director and taught dance. She fell in love with a young businessman, William Warren, and they were married in 1942. But the travel his job required, along with his alcoholism, took a toll on their relationship, and they divorced five years later.

She met Gerald Ford in 1947, as her divorce was pending, and their courtship proceeded discreetly so as not to be interpreted as an affair. He proposed to her in late 1947 or early 1948—the couple disagreed on the date—with the proviso that they not get married right away. He would not tell her why. The reason, she later learned, was that he had plans to run for the House of Representatives from Michigan’s Fifth Congressional District, and marrying a woman who not only was divorced but also a former dancer was seen as a liability by his advisers in securing the Republican nomination that September. A month after his win, and just two weeks before the general election, on Oct. 15, 1948, Betty Bloomer Warren became Mrs. Betty Ford.

Betty Ford and her daughter, Susan, take in the view from the White House in April 1975, several months after the first lady’s breast cancer diagnosis and radical mastectomy. Photo by David Hume Kennerly / Getty Images

The Fords went on to have four children between 1950 and 1957. Gerald Ford, likable and respected by his fellow members of Congress, held his seat for 25 years. His ultimate goal was to become Speaker of the House, but the political turmoil of the time catapulted him into a position of even more responsibility. In October 1973, Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned a few months after the U.S. attorney’s office charged him with tax evasion, money laundering and bribery for actions he had taken as governor of Maryland. President Nixon chose Gerald Ford as Agnew’s successor, and both houses of Congress confirmed the nomination. Ten months later, Nixon resigned, making Gerald Ford the first—and only—person to serve as president who had not been elected to either the vice presidency or the presidency.

Breast Cancer Advances

When Betty Ford was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1974, a mastectomy—often a radical mastectomy involving removal of the breast, muscle and lymph nodes—was the standard of care. And as Ford experienced, the time from diagnosis to surgery was very brief. “Often, biopsy was an open procedure in the operating room,” says Richard Theriault, a medical oncologist at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “The women would sign consents to have a biopsy and then a mastectomy, if the biopsy was positive—meaning it was cancer.” As a result, a woman often entered the operating room not knowing whether she would wake from the anesthesia with or without her breast.

In the 1960s, a few doctors began promoting the idea that less extensive surgery might be as effective as a radical mastectomy, and in 1971 the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) began enrolling women in a study comparing the effectiveness of radical mastectomy versus simple mastectomy (removing the breast alone) with or without radiation. The study eventually showed all three treatments were equally effective. In 1976, the NSABP launched the B-06 trial, which would later show that lumpectomy followed by radiation was as effective as a mastectomy.

As a result of these NSABP studies, “the surgery has changed completely,” says Deborah Capko, a surgical oncologist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Now, most women who have small tumors opt for lumpectomies rather than mastectomies. And instead of removing all of the lymph nodes under the arm to determine if the cancer has spread, surgeons now typically remove and examine one node, known as the sentinel node. If the sentinel node is negative for cancer cells, patients do not need to have more extensive lymph node removal, which can cause short- and long-term side effects, such as pain and swelling.

Concurrent with the studies looking at the effectiveness of surgery and radiation, researchers were also evaluating new kinds of systemic treatments. This research resulted in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval, in 1977, of the drug tamoxifen for metastatic tumors. The next big development occurred in 1998, when the drug Herceptin (trastuzumab) was approved for the treatment of metastatic breast tumors that make too much of a protein called human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, or HER2. These drugs, along with the anti-estrogen drugs called aromatase inhibitors, were subsequently approved for the treatment of early stage tumors, ushering in the current era of breast cancer care in which a tumor’s estrogen, progesterone and HER2 status is used to guide treatment choices.

Public Awareness Increases

By speaking out, Ford broke through the existing taboos surrounding breast cancer. “Betty Ford’s openness about her breast cancer experience was revolutionary,” says Dubriwny. “It provided the media with the opportunity to do all different types of reporting about breast cancer.”

Her openness was also a boon for breast cancer research. “The momentum that was being created by the need to do something about breast cancer and women’s health, highlighted by Betty Ford, electrified the community,” says V. Craig Jordan, a molecular pharmacologist at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in Washington, D.C., who conducted the first systematic lab research on tamoxifen’s use in breast cancer. It gave the research community the publicity it needed “to move forward.”

There was a political dimension as well: Press coverage of Ford’s cancer served as a distraction from Watergate and the political fallout of her husband’s decision to issue a full pardon to former President Nixon for all offenses he may have committed during his presidency. The media coverage “humanizes Betty Ford, but it also humanizes President Ford in a way that simply couldn’t have been done otherwise,” Dubriwny says.

Betty Ford enjoys a moment at home in Rancho Mirage, Calif., with Gerald Ford in 1985. The now famous rehabilitation center that bears her name opened in the city three years earlier. Photo by David Hume Kennerly / Getty Images

A year after her diagnosis, Betty Ford accepted a special award at an American Cancer Society (ACS) dinner in New York City, where she gave a speech describing her experience. “One day,” she told those gathered, “I appeared to be fine and the next day I was in the hospital for a mastectomy. It made me realize how many women in the country could be in the same situation. That realization made me decide to discuss my breast cancer operation openly, because I thought of all the lives in jeopardy.” She also acknowledged the emotional and psychological toll that breast cancer can take: “Too many women are so afraid of breast cancer that they endanger their lives. These fears of being ‘less’ of a woman are very real, and it is very important to talk about the emotional side effects honestly. They must come out into the open.”

Ford also became a spokesperson for the ACS and began advocating for early detection and screening. Her activism fit into her overall support for women’s issues. She publicly supported the Equal Rights Amendment, even making phone calls from the White House to lobby state legislators to vote for passage—a move criticized by opponents of the measure.

After Gerald Ford lost the presidential election to Jimmy Carter in 1976, the Fords retired to southern California. For many years, Betty Ford had struggled with alcoholism and addiction to prescription painkillers, and in 1978, her family staged an intervention, and she checked into the rehabilitation facility at Long Beach Naval Hospital. Soon after her release, she spoke with a friend, another recovering alcoholic, who was interested in starting a rehabilitation center. Ford had noticed that the rehab programs catered to the issues faced by men, and the two friends decided to raise money for a facility that would address the needs of women. In 1982, the Betty Ford Center at Eisenhower Medical Center opened in Rancho Mirage, Calif. The center reserved—and still reserves—half of its space for women and treats men and women in separate programs. Many high-profile celebrities have sought treatment at the nonprofit center, which draws from the 12-step Alcoholics Anonymous philosophy and emphasizes group therapy.

Betty Ford died of natural causes on July 8, 2011, in Rancho Mirage, at the age of 93. Her time in the White House was short, but the impact she made due to her openness about her breast cancer diagnosis as well as her personal struggles with addiction was long-lasting. Dubriwny believes Ford remains one of the most endeared first ladies because of the optimism she embodies. “When faced with adversity,” she says, “Betty Ford came through and survived in a way that made the American public love her.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.