MEGAN ALEXANDER had a heart attack before she turned 2. The culprit: A chemotherapy drug used to treat rhabdomyosarcoma, the rare cancer she was diagnosed with when she was only 10 days old. The drug, Adriamycin (doxorubicin), had irreparably damaged her heart tissue. But it had also helped save her life, as did the radiation treatment she received.

Today Alexander, 24, of Chicago, returns every year to West Michigan Heart, a clinic in Grand Rapids that is now part of Spectrum Health, for tests more familiar to a senior citizen with heart valve disease than to a young woman just starting her career. She also manages lingering physical challenges from her illness and treatment for the brain tumor that had grown in her left frontal lobe. Despite residual weakness and mobility issues on the right side of her body, Alexander walks for exercise every day with her service dog, Blue, who also rides with her on Chicago’s elevated train to her job as a cancer support specialist with Imerman Angels, a nonprofit that connects cancer patients with mentors and caregivers. In her work, Alexander matches newly diagnosed patients with mentors who have been through treatment. She has also mentored the parents of two children who, like her, were diagnosed with brain tumors. “I assure them that I’m still here. I survived the tumor, and I’m doing great,” she says.

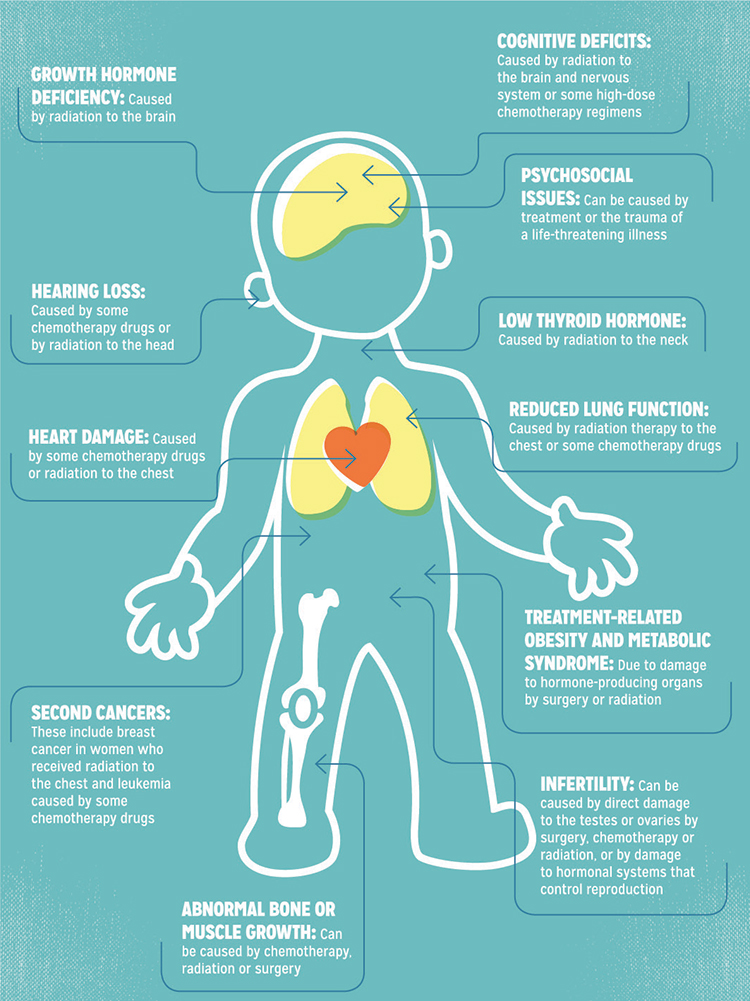

Childhood cancer survivors can face long-term effects from treatment.

A Medical Success Story

The treatment of pediatric cancers has been one of the great medical success stories of the past 50 years. A half century ago, only about 30 percent of children with cancer survived. Now, more than 80 percent of children diagnosed with a pediatric cancer will become long-term survivors. With this achievement has come rising awareness that successful treatment can come with costs.

“Back in the 1970s, we started to recognize the adverse consequences of some pediatric cancer therapies, as survival rates were improving and cancer survivors increased in number,” says Leslie Robison, an epidemiologist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, who has studied pediatric cancer survivors for more than 40 years. But it was hard to piece together a comprehensive understanding of the long-term consequences of treatment from the small number of case studies appearing in the 1970s and 1980s, he says.

To fill in the gaps, in 1994 Robison and his colleagues launched the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), which has tracked the health status of more than 14,000 adult survivors of childhood cancer who were diagnosed between 1970 and 1986. This huge project, along with smaller studies at survivorship clinics around the world, has allowed oncologists to develop a basic road map for what young survivors might experience as they grow older.

Many of these long-lasting side effects, often referred to as late effects, are not unique to children. If a potential consequence of chemotherapy or radiation therapy takes 20 years to become evident, however, adults treated in their 60s may not live long enough to experience it. But today, children treated for cancer most likely will live to an age when late effects can appear.

Results from the CCSS and smaller studies have found that more than 60 percent of adults treated for cancer when they were children develop at least one chronic health condition. While some of these are minor and do not affect quality of life, others are severe and can be life-threatening. A recent study of more than 1,700 adult survivors of childhood cancer published in the June 12, 2013, Journal of the American Medical Association estimated that about 80 percent would develop a serious, disabling or life-threatening chronic health condition by the age of 45. Conditions associated with cancer treatments included infertility, hormone irregularities, heart attack, obesity, diabetes, nerve damage and kidney dysfunction.

Long-term survival prompts new treatment regimens.

As survival after childhood cancer has improved over the past few decades, many treatment regimens have slowly changed. For some types of childhood cancer, the focus of clinical trials has turned to making treatment less likely to cause problems down the road, since the vast majority of patients are now expected to survive. Reduced therapy and less toxicity in required treatments “is the goal of much ongoing research and pediatric cancer trials,” says Melissa M. Hudson, an oncologist who directs the Cancer Survivorship Division at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Successful trials have already led to new treatment regimens that reduce the use of radiation on the vulnerable central nervous system, and researchers continue to test whether new combinations of chemotherapy drugs can reduce both short- and long-term toxicity while maintaining the survival rates achieved with older, more intensive treatments.

In 2007, the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study began recruiting a second group of 14,000 childhood cancer survivors, after first doing so in 1994, to better understand how late effects of treatment are evolving as therapeutic approaches change. The first set of data ready for analysis from this group will be available this fall, says Leslie Robison, an epidemiologist at St. Jude.

Hudson says it is the oncologist’s responsibility after treatment to monitor the patient for late effects and remind the family of risks. However, sometimes the only way primary care physicians can learn about late effects is if survivors keep them informed about their health, says Hudson. “I encourage them to stay informed and potentially engaged in research about late health outcomes,” she says of physicians, which can help them understand the patterns in the health problems long-term survivors face.

Addressing Late Effects

A discussion of the potential late effects of cancer treatment may get drowned out in the panic surrounding a cancer diagnosis. Talking about late effects “is a standard part of our discussion of therapy for children with cancer,” says Melissa M. Hudson, a pediatric oncologist who directs the Cancer Survivorship Division at St. Jude. But if “you’ve just been told that your child has cancer, it’s very hard to hear anything other than ‘my child has cancer.’ ”

Compounding the problem, information about late effects may not be remembered years or decades after treatment. Parents also vary in the amount of information they pass on to their children as they grow older, says Hudson. Some parents make sure their children know everything about their treatment and its potential side effects; others shelter their children completely, figuring they’ve been through enough already.

“As far as I remember, we were told nothing,” recounts Jeff Krause of Chicago, who was diagnosed with stage IV Hodgkin lymphoma in the mid-1970s and completed treatment before he was 12. “My parents didn’t tell me at the time, but the doctors gave me about a 20 percent chance of surviving. It used to be a death sentence, and I think they were just thrilled that I was alive, that I responded so well to the chemotherapy.”

Krause is now 48 and his lymphoma hasn’t returned. A few years ago, he began to hear more about the late effects of cancer treatment and decided to do his own research. He found a local clinic for adult survivors of childhood cancer, the STAR Survivorship Program at Northwestern University’s Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chicago. They helped him piece together his cancer treatment history and ran him through a battery of tests designed to screen for potential effects of the treatments he had received.

His efforts proved worthwhile—a cardiologist discovered damage to his heart valves caused by radiation therapy to his chest. “She said I have the valves of a much older person—that she would probably guess I was 15 to 20 years older than I am based on their condition,” he says. Although he currently experiences no symptoms from the damage, he needs to be monitored yearly to make sure his valves don’t need replacement. Krause credits his primary care doctor for being aware of many of the late effects of cancer treatment and keeping an eye out for some of the most common, such as thyroid cancer.

In 2005, the Institute of Medicine released a report that highlighting the need for all cancer survivors … to receive a survivor care plan that includes information about their cancer and how it was treated, and mentions screening tests that should be incorporated into routine health care appointments. Yet a recent study by Eugene Suh, a pediatric oncologist who directs the Childhood Cancer Survivorship Clinic at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, suggests these plans are not being provided. Suh’s survey of more than 1,000 internists in the U.S., published Jan. 7, 2014, in the Annals of Internal Medicine, found that more than half were caring for at least one survivor of childhood cancer—and more than 70 percent of these doctors did not have a treatment summary for these patients. “That’s a staggering number, because [the treatment summary is] the foundation of the knowledge that survivors need as they move forward,” says Suh.

In a study published in 2009 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, CCSS investigators, including Hudson, found that only 18 percent of survivors being tracked had received counseling or screening tests for the long-term side effects associated with their cancer treatments. Tests and interventions that can benefit survivors include breast MRI screenings in addition to mammograms for pediatric cancer survivors who received radiation to the chest. Other examples include heart monitoring to screen for valve dysfunction, disruption of the heart’s electrical system or damage to the heart muscle; hormone replacement for thyroid damage; hearing aids or cochlear implants for hearing damage caused by some chemotherapy drugs; and counseling to encourage survivors to focus on maintaining healthy behaviors throughout their lives.

Care plans are especially important for childhood cancer survivors when they head off to college or leave home to pursue a career or start a family. Chelsea Makela, now 24, who had brain surgery in 1998 at age 8 to remove a part-malignant tumor, moved from a small agricultural town in the San Francisco Bay Area to Los Angeles when she was 18 to pursue an acting career. There she found the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Healthy Lives After Cancer program, which was started in 2009 at UCLA’s Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center to help teen and young adult cancer survivors get access to survivorship information and resources, and which provided Makela with a comprehensive screening plan. She knows that many survivors are cut loose from their pediatric oncologists when they turn 18 and can feel lost making the transition to oncologists who treat mostly adults. “If I hadn’t found the UCLA team, that’s exactly how it would have happened to me,” she says. Program faculty members have even helped her pursue her dream to develop a cancer diary and doll that will assist children going through cancer treatment to better explain what they’re experiencing to family members and friends.

Providing a Road Map

Marc Horowitz and David Poplack, both pediatric hematologists-oncologists, have been leading a team at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Cancer Center in Houston to develop a comprehensive Internet-based survivor care plan for children and young adults. Since 2007, the plan, called Passport for Care, has been made available to doctors affiliated with the Children’s Oncology Group (COG). Institutions that are COG members manage treatment for almost all children diagnosed with cancer in the U.S. As of June, Horowitz says, cancer care plans have been developed for more than 14,000 pediatric cancer survivors through Passport for Care; both doctors and pediatric cancer survivors can view care plans on the Passport for Care website. The team will launch a survivor portal this fall that will give survivors direct access to their treatment histories and guidelines for their care. With the help of a patient navigator hired by the team, survivors who never received a treatment summary will be able to piece together their medical history and plan for the future.

It’s also important for parents to explain to their children why the care plan is important for their future health and why they should make sure any doctor they see knows about their childhood cancer and their care plan.

“My parents always taught me, ‘It’s your body, your treatment. You’re allowed to ask questions,’” says Makela. “Just because a doctor says, ‘This is what we’re going to do,’ if you don’t understand it, or if you want to learn about another route, it’s OK to ask. I think that’s one of the most empowering tools a parent can give a child—a sense of confidence about being in charge of their health.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.