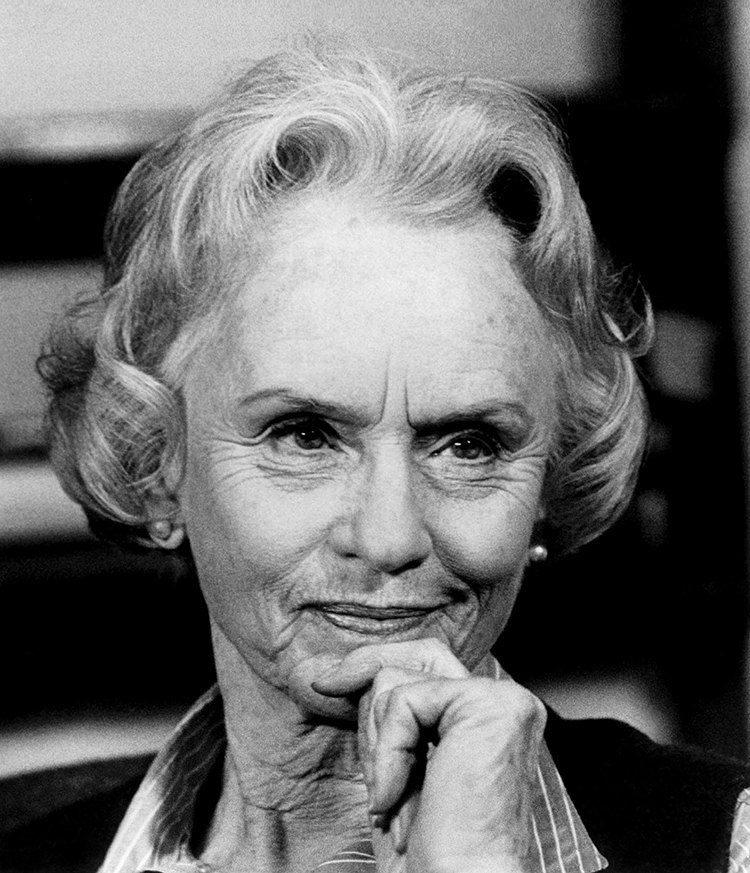

A year after Jessica Tandy won the Academy Award for Best Actress in 1990 for the title role in Driving Miss Daisy, she returned to the Oscars to present the Best Actor award. Only short wisps of her silver-white hair remained after aggressive chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer, diagnosed months earlier. Still, Tandy, in a broad-shouldered gunmetal gown, sparkled.

Photo © AF Archive / Alamy

Before the awards ceremony, Oscar handlers had offered her a cap to wear onstage. But Tandy, who the previous year had become the oldest woman to win a Best Actress award, tossed the idea aside. “She thought, ‘No, I’m just going to go as I am,’ ” her daughter Tandy Cronyn recalls. The 81-year-old trouper delivered her lines that March night with the elegance and resonance that characterized her more than six-decade-long acting career.

A Theatrical Calling

Jessie Alice Tandy, born in London on June 7, 1909, might have credited her start in theater in part to a lengthy illness, which prevented her from finishing high school, her daughter says. With the door to college closed and an interest in acting nurtured by trips to the theater, drama school beckoned.

First appearing on stage at age 18 in a backroom London theater in The Manderson Girls, Tandy later caught critics’ eyes in 1932 with her leading role as Manuela in the play Children in Uniform in London. “She was off and running,” her daughter says—on a career that would include work with the likes of Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud and Alec Guinness.

In 1932, two years after a brief stint in New York City for her Broadway debut in The Matriarch, she married British actor Jack Hawkins, with whom she had a daughter, Susan. Eight years later, Tandy and Susan moved from England to New York City, where Tandy struggled to make ends meet with intermittent supporting parts on Broadway and a recurring role on radio’s Mandrake the Magician. She met her partner in drama and in life, actor Hume Cronyn, backstage in 1940 while she was appearing in the play Jupiter Laughs.

The couple married in 1942, after Tandy and her first husband divorced. Making their new home in Hollywood, Tandy and Cronyn had a son, Christopher, and their daughter, Tandy. Over the next few years, Jessica Tandy endured a stretch of lackluster film roles. But a Los Angeles stage production directed by Cronyn reinvigorated her stage career. Portrait of a Madonna, a one-act Tennessee Williams play that had been optioned by Cronyn, showcased Tandy in a role that was a prototype for the character of Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire. Tandy’s performance in Los Angeles earned her the Broadway role of Blanche in 1947 and led to her first Tony Award—for best actress in the play that would give Williams the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Jessica Tandy won a 1948 Tony Award for her Broadway portrayal of Blanche DuBois in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, starring alongside Marlon Brando. Photo by Eliot Elisofon / Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images.

For much of their 52-year marriage, Tandy and Cronyn were considered the “first couple” of the American stage, and their work together in The Gin Game in the late 1970s and in Foxfire in the early 1980s earned Tandy two more Tony awards for best actress in a play. A New York Times critic declared, “Only poets, not theater critics, should be allowed to write about her.”

In all, Tandy’s career included more than 100 plays and more than 25 films, as well as multiple television productions. The prominent position she and her husband held in the arts was highlighted when each was recognized in 1986 with Kennedy Center Honors and, in 1990, with the National Medal of Arts. In 1994, the couple was awarded the first Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Her career was dotted with roles in films including The Birds, The World According to Garp and Cocoon, but it was the success sown by her Oscar-winning performance as the Jewish widow at the heart of the 1989 film Driving Miss Daisy that made Tandy a household name late in life. She was riding the wave of that success when her cancer was diagnosed.

Early detection is an elusive goal.

Diagnosed and treated before it spreads from the ovary, ovarian cancer has a five-year survival of 92 percent. But only 15 percent of ovarian cancers are caught this early, and no one has found a reliable test that can detect the cancer in most women before symptoms arise.

One challenge is that ovarian cancer is relatively rare—the average woman has a 1 in 73 lifetime risk of developing the disease, according to the National Cancer Institute. This infrequency requires a screening test that will yield few false positive results, to ensure it doesn’t flag more people without the disease than with the disease, says Anna Lokshin, a pathologist who specializes in diagnosing gynecologic and other cancers at the University of Pittsburgh’s Hillman Cancer Center. And because ovarian cancer progresses rapidly, she adds, the screening test would need to find the disease at least a year earlier than the cases that are now being diagnosed to improve treatment success.

The CA125 blood test, which looks for a protein that is typically found in higher concentrations in ovarian cancer cells than in normal cells and that is released into the bloodstream, is used to monitor how a woman’s cancer is responding to treatment. But because the test can miss early tumors, it hasn’t proved to be a great tool for screening, says Deborah Armstrong, a medical oncologist at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. However, in April 2009, researchers from a U.K.-based study of more than 200,000 women reported preliminary findings that annual CA125 screening, interpreted through a risk formula called ROCA (Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm) that weighs changes in CA125 levels and the patient’s age, plus transvaginal ultrasound as a second-line test—or just the ultrasound alone, performed annually—may be feasible screening strategies. The researchers plan to report results in 2015 that may reveal whether the strategies can decrease ovarian cancer mortality.

Diagnosis: Ovarian Cancer

Tandy’s disease was discovered in August 1990, after a series of visits to the doctor with vague complaints—weight loss, feeling ill—but no answers. Finally, her daughter recalls, imaging revealed a fist-sized ovarian tumor as well as smaller masses scattered throughout her abdomen.

Her treatment at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City included surgery to remove as much of the cancer as possible—a procedure known as debulking—followed by intravenous chemotherapy, including Platinol (cisplatin). Tandy Cronyn says, “They really zapped the living daylights out of her.”

Modern anti-nausea medications, which today help patients endure such a toxic onslaught, were still being developed when Jessica was diagnosed, her daughter adds. Cancer and chemo, Jessica Tandy told an interviewer in 1992, “takes the stuffing out of you.”

These body changes could signal ovarian cancer.

Research has shown that a specific set of symptoms—along with how frequently they occur and how long they last—can help identify women with ovarian cancer. Those symptoms can also have many other causes, experts note. But they may represent an important chance to recognize ovarian cancer, if it is present. According to the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance, women should see a gynecologist if the following symptoms occur more than 12 times a month or are new or unusual:

- Bloating

- Pelvic or abdominal pain

- Problems eating, or feeling full quickly

- The need to urinate frequently or urgently

Other symptoms of ovarian cancer can include abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding, back pain, and constipation or diarrhea.

Identifying Symptoms

Today, ovarian cancer remains challenging to diagnose early. And, despite decades of effort, an effective screening test has not been developed. (See “A Screening Challenge.”) The American Cancer Society estimates that 22,240 women will be diagnosed with the disease this year in the United States and that 14,230 will die of it. According to the National Cancer Institute, only 15 percent of ovarian cancers are found before they have spread beyond the ovary; most will be stage III or IV cancers that have spread to the abdominal lining, the lymph nodes or beyond before symptoms are noticed or a diagnosis is made.

Like Tandy, many patients wind up going through a “million-dollar workup,” for unexplained abdominal pain or gastrointestinal symptoms before they receive the correct diagnosis, says Deborah Armstrong, a medical oncologist at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. To potentially avoid that, Armstrong says, whenever a woman is experiencing vague abdominal symptoms (see “Know the Symptoms” above), the possibility of ovarian cancer should be considered, and the doctor should perform a pelvic ultrasound and a blood test for the CA125 protein, which tends to be found at higher levels in many women who have ovarian cancer.

Photo by Ron Galella / WireImage / Getty Images

Treatment Advances

Surgical management of ovarian cancer has been largely the same since the time Tandy was diagnosed, says Robert Burger, a gynecologic oncologist and director of the Women’s Cancer Center at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. But over the past decade, efforts have been made to have gynecologic oncologists perform surgery on women suspected of having ovarian cancer rather than obstetrician-gynecologists or general surgeons. (Research has shown that patients operated on by gynecologic oncologists fare better, Burger says.) Another improvement: A once-common practice called a “second-look surgery” to judge a patient’s prognosis after chemotherapy has been completed—has become obsolete. Research indicated that half of patients who had no cancer detected in such surgeries still ended up with recurrences, Burger says.

Over the past two decades, doctors have been able to improve chemotherapy treatments. Studies have identified multiple chemotherapy regimens that are more tolerable and effective than previous approaches, with Taxol (paclitaxel) and Paraplatin (carboplatin) now typically used intravenously instead of Platinol (cisplatin) and Cytoxan (cyclophosphamide). “We haven’t really been able to break out subsets [of patients] that seem to benefit from one [new] approach versus another, although that’s obviously a topic of study,” Burger says.

Intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy—delivered into the abdomen, where the cancer is—was available in Tandy’s time and was bolstered largely by a 2006 study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, which suggested that women with advanced ovarian cancer experience improved survival if they receive IP chemotherapy in addition to their intravenous chemotherapy. But the treatment is tough on patients, and many doctors are awaiting further research to clarify its benefits. Meanwhile, neoadjuvant chemotherapy—chemo given before surgery to try to shrink the cancer—became recognized as a solid option for patients with stage III or IV cancers who are unable to have surgery right away due to other health problems or whose surgery is unlikely to be successful based on the location or extent of the disease.

More recently, clinical trials have suggested that the targeted therapy Avastin (bevacizumab), which blocks the growth of the blood vessels that tumors need to survive, can delay disease progression in some women with advanced or recurring ovarian cancer. Avastin has not been proven to lengthen survival and has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as an ovarian cancer treatment. Yet Burger says even though clinical trials haven’t conclusively shown a survival advantage, doctors report that some patients who have become resistant to multiple chemotherapy drugs have seen their condition stabilize with Avastin. And a recent survey of oncologists found that the drug’s use as a first-line treatment for advanced ovarian cancer is commonplace. Meanwhile, new drugs called PARP inhibitors, which work in part by blocking a DNA repair mechanism, are now in various stages of clinical trials, including phase III trials. Early trials suggest these drugs may be especially effective in the small percentage of ovarian cancer patients who have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic mutation.

Another crucial development has been the improvement of supportive care to prevent or alleviate disease symptoms or treatment side effects. That care has allowed some patients to resume normal activities, including work, while they’re on treatment. Helen Palmquist, who was diagnosed in 1987 with stage III ovarian cancer just before her 42nd birthday, has seen these dramatic changes firsthand. “The words ‘quality of life’ hadn’t been invented,” back then, says Palmquist, who faced nausea and subsequent weight loss. “Now they have great drugs for nausea.”

A Lioness Until the End

The initial treatment Tandy received kept her cancer under control. But in 1992, she experienced her first recurrence. She told a British tabloid that she had conquered it before and would do so again. “I have not finished yet,” she said, noting that while her chemo was cruel, “it’s not as bad as it used to be.” The next year, with her cancer temporarily under control, she worked on two feature films and a TV movie. But the cancer hung overhead “like a Sword of Damocles,” her husband told an interviewer. “Jessica,” he said, “has the courage of a lioness.”

Jessica Tandy died of ovarian cancer on Sept. 11, 1994, at age 85. She was at home in Easton, Conn., with Hume at her side. Just three months earlier—at the end of a career two-thirds of a century long—she and her husband had accepted their lifetime achievement Tony. “I am particularly grateful,” she said, “for the opportunity to step once more upon the stage.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.