William G. Nelson, MD, PhD Photo by Joe Rubino

ANTIBODIES THAT CAN SIMULTANEOUSLY BIND both to cancer cells and to immune cells—some of them given the trademarked name BiTEs, for bispecific T-cell engagers, by the biopharmaceutical firm Amgen—make up a growing collection of anticancer drugs that act to bring cytolytic T cells, the kind of immune cell that can kill cancer cells, near the target cancer cells. Since the Food and Drug Administration approved the bispecific antibody Blincyto (blinatumomab) for the treatment of relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 2014, a total of 10 such antibodies have been introduced into cancer care.

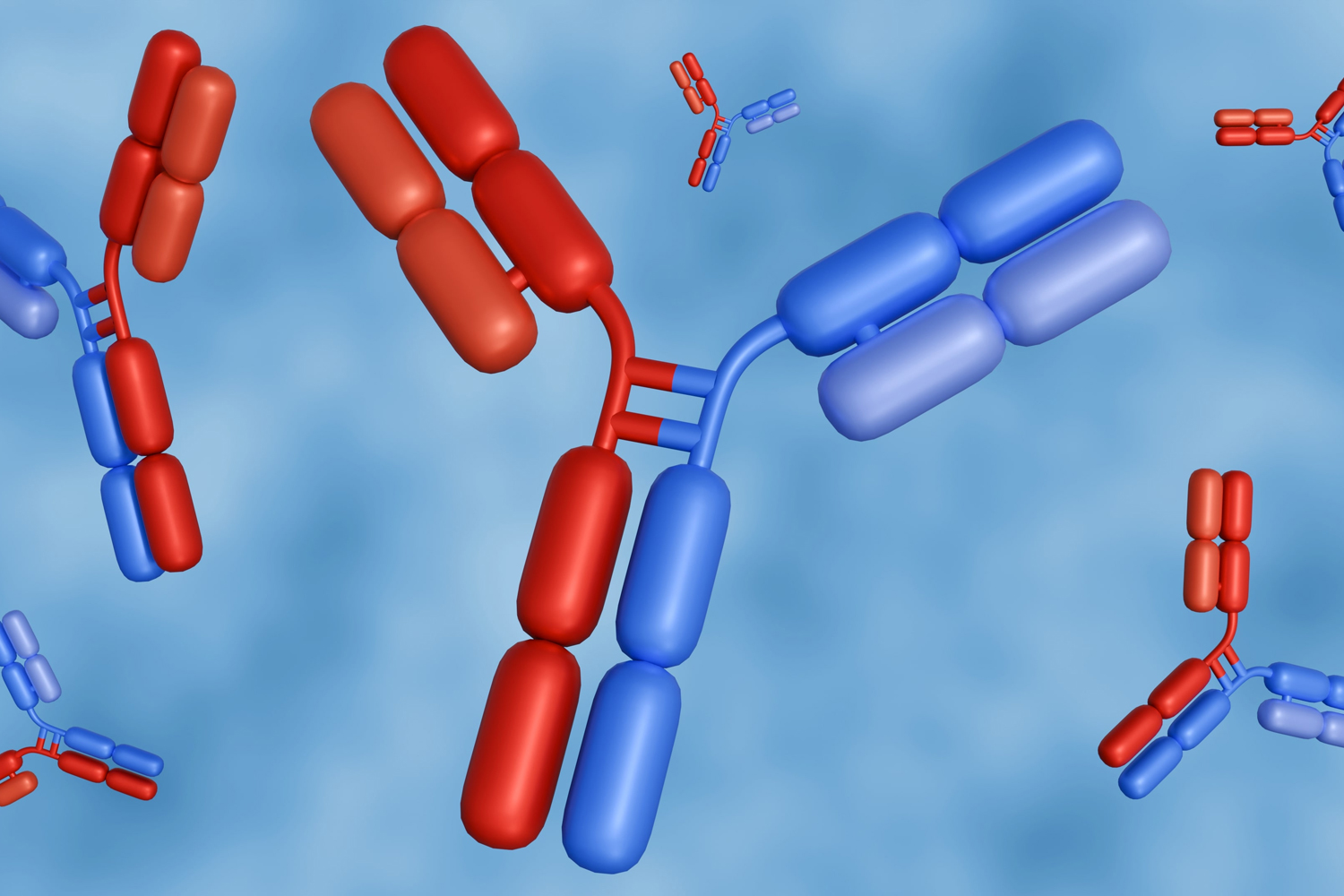

Natural antibodies produced as part of the body’s immune response are Y-shaped proteins capable of binding two identical targets (at the two “arm” segments of the Y), such as the proteins and carbohydrates that coat bacteria and viruses. The bispecific antibodies are constructed so they are able to attach to two different targets (containing two different arms). This means one of the binding targets can be located on the surface of the cancer cells to be eradicated, and the other can be found on the surface of cytolytic T cells. These antibodies have been termed T-cell engagers. When a T-cell engager antibody has bound both of its targets, cytolytic T cells are close enough to the cancer cells to be able to destroy them.

T cells are immune cells long understood to be capable of distinguishing host from microbe, which protects against infection, and one person’s cells from another person’s cells, which tends to promote organ rejection after transplantation. An estimated 400 billion T cells reside in each individual, and they are able to recognize an unimaginably large number of different molecular features of bacteria, viruses and normal cells. T cells can also distinguish cancer cells from normal cells, though in someone with a growing, life-threatening cancer, the T-cell responses appear inadequate to control or eliminate the tumor cells.

The idea motivating the design of T-cell engager antibodies is that they might recruit cytolytic T cells, regardless of their innate specificities, and redirect them to bind and destroy cancer cells. In this way, T-cell engager antibodies can draft very large numbers of cytolytic T cells into the fight against cancer. This tactic is reminiscent of the strategy underlying the use of chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR T cells), where diverse T cells harvested from the body are genetically altered to recognize and kill cancer cells and then reinfused back into the body. While CAR T cells need to be created for each individual patient, bispecific T-cell engager antibodies represent an off-the-shelf product. On the other hand, the T-cell engager antibodies require repeated administration, while CAR T cells often persist and expand after a single infusion.

Treatment with T-cell engager antibodies and CAR T cells can cause similar side effects, particularly cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), not typically seen with other anticancer treatments. CRS involves high fevers, low blood pressure and other signs and symptoms of severe illness. People who have CRS often require intensive care, and some do not survive. ICANS, characterized by headache, delirium, agitation and seizures, can also be life-threatening. Fortunately, new approaches to administration of T-cell engager antibodies and CAR T cells have begun to mitigate and even prevent severe CRS and ICANS. As a consequence, both of these treatment approaches should become safer moving forward.

T-cell engager antibodies are well on their way to transforming the care of multiple myeloma and certain leukemias and lymphomas, and they are just beginning to gain a foothold in diseases like small cell lung cancer. In the movie Jurassic World, when confronted with a menacing dinosaur bent on destroying everything around it, the character Gray Mitchell suggests “we need more teeth” to defeat the terrifying monster. The same may be true for cancer treatment using BiTEs and other T-cell engagers.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.