WHILE MOST PEOPLE have had a case of hiccups they can’t shake, people undergoing certain treatments for cancer may have more than their fair share of this annoyance. One 2021 study published in the American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine surveyed 213 cancer patients, finding 16% experienced hiccups and 5% had significant problems with hiccups. Meanwhile, a study published June 15, 2022, in BMC Cancer found that among cancer patients who reported hiccups, 62% experienced them daily.

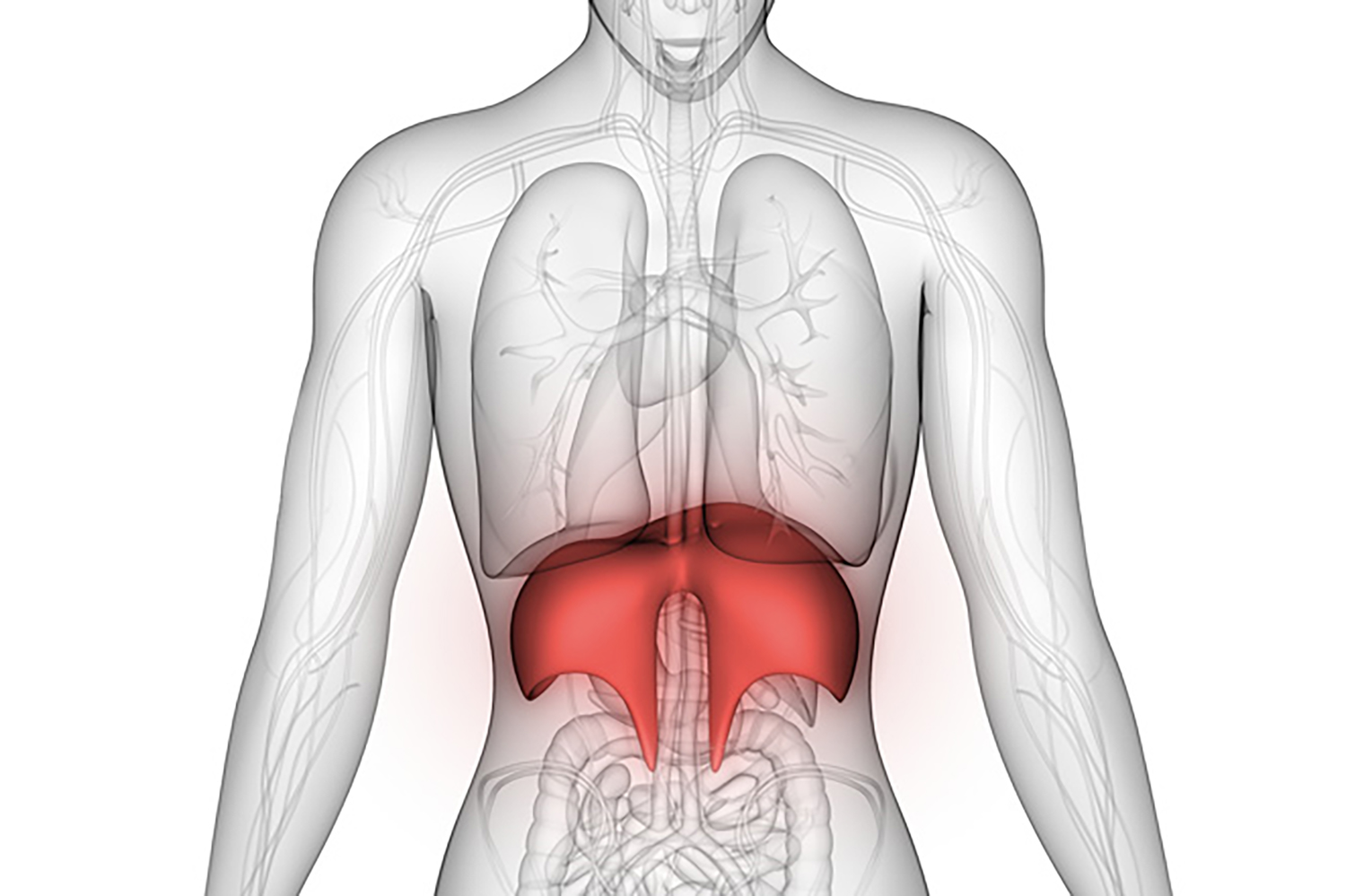

Hiccups are involuntary contractions in the diaphragm, a dome-shaped muscle below the lungs that automatically contracts and relaxes to help the lungs expand and contract. When irritated, the diaphragm spasms, resulting in hiccups. Most cases resolve on their own or with home remedies, but hiccups that last for more than 48 hours may be addressed with medication.

According to Thomas Smith, a medical oncologist and director of palliative medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, hiccups are particularly common among those taking dexamethasone, a steroid that helps with chemotherapy side effects like nausea, vomiting and allergic reactions. Other medications that can cause hiccups include some sedatives and anti-anxiety medications cancer patients sometimes take, as well as certain anti-cancer drugs including carboplatin, oxaliplatin, fluorouracil and irinotecan.

Flavio Rocha, a surgical oncologist at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, says narcotics, which many people with cancer use to manage pain, and electrolyte imbalances caused by chemotherapy can lead to hiccups. He also says tumor and surgical complications can “affect the function of the diaphragm and, therefore, cause hiccups.”

Smith says hiccups are most common “in people with abdominal malignancies that irritate the diaphragm, like gastric, pancreatic and sometimes ovarian cancer.” According to Rocha, if abdominal organs like the stomach, liver or pancreas become filled with fluid or obstructed by a tumor, the diaphragm can become irritated. Also, if cancer affects nerves connected to the diaphragm or spreads in the abdominal cavity, coating the diaphragm, hiccups can even be a cancer symptom.

Hiccups are “very much underreported” by patients, Smith says. He thinks this is because chemotherapy can cause many uncomfortable side effects, often turning people’s lives upside down. If bothersome hiccups occur on the second day of chemotherapy but have subsided by the time of the next cycle, patients may not think to mention them to their care team.

“There is no one cure-all for hiccups,” Smith says. There is only one Food and Drug Administration-approved drug for hiccups, but he says there are plenty of other options for managing them. Some home remedies he recommends include sipping or gargling with cold water, swallowing dry sugar or vinegar, biting into a lemon, holding your breath, pulling on your tongue, gently pressing on your eyeballs, and compressing the chest by sitting down and pulling your knees up. The American Cancer Society also recommends other approaches including special breathing techniques. “While we don’t know how effective these methods are, they are generally safe and easy to try,” Smith says.

For hiccups that last for days or weeks, talk to your doctor about what could be causing the problem. Rocha emphasizes the importance of identifying any underlying structural issues that may be causing hiccups. Your doctor may recommend some medications that can help, such as proton pump inhibitors or muscle relaxants. According to Smith, switching to a different steroid, such as methylprednisolone, can help stop hiccups.

“If one [approach to treating your hiccups] doesn’t work, partner with your health care team and try something else,” says Smith. “You may have to try four or five medications before finding one that works for you and has acceptable side effects.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.