NEW RESEARCH SHEDS LIGHT on an apparent contradiction in prostate cancer treatment: that controlling cancer growth can be achieved both by lowering hormone levels and, in some cases, by raising them.

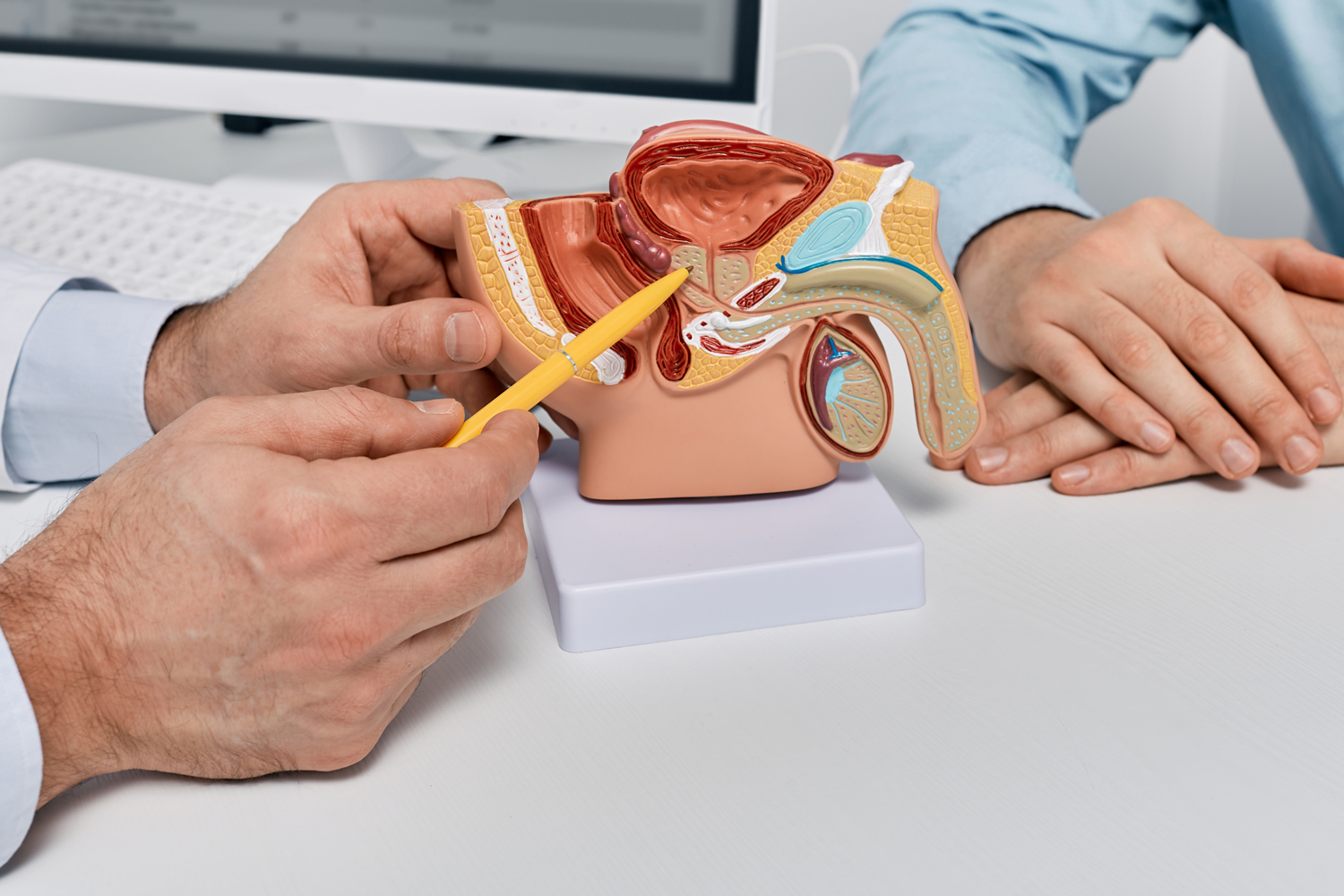

Men in the early stages of prostate cancer typically undergo androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), which uses prescription medication to lower the levels of androgens, male hormones including testosterone, or block their action in prostate cells, stopping them from fueling cancer cell growth.

Yet, 10% to 20% of men with prostate cancer on ADT will be diagnosed with castration-resistant prostate cancer—usually at an advanced stage of the disease called metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC)—in which the cancer continues to grow even when testosterone levels are reduced to very low levels.

For men with mCRPC, the next step in treatment can be chemotherapy, radiation or both, which can have toxic side effects. But a new treatment concept that gives men more testosterone may help them stay on hormone therapy longer, delaying the need for more aggressive forms of treatment. Known as bipolar androgen therapy (BAT), it uses high doses of the male hormone testosterone to suppress tumor growth. When a doctor notices signs of disease progression, they can change back to ADT.

“It seems counterintuitive, but we’ve found that in some patients whose prostate cancer is growing despite being on hormone-blocking drugs, treating with high-dose testosterone has an effect on progression of the disease and resensitizes the [cancer] cells so they respond to androgen deprivation therapy again,” says Samuel Denmeade, a medical oncologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

For over a decade, Denmeade and his research team have been studying how these seemingly contradictory treatments work through clinical trials that include men who have prostate cancer that is resistant to ADT but don’t have symptoms of the disease. In Denmeade’s research, men with mCRPC are given a monthly 400 milligram injection of a generic form of testosterone, known as testosterone cypionate, every 28 days, which is at the high end of an FDA-approved dose. “The patient population we treat are usually men in their 60s, 70s and 80s. Their blood testosterone level, if they weren’t medically castrated, would probably be 300 to 400. But our treatment will get their testosterone level up to 2,000,” Denmeade says. Patients continue on this regimen until their prostate cancer progresses, signaled by symptoms or changes on imaging scans, and then they’re switched back to ADT.

“What we’re hoping to do by cycling between very high and very low testosterone levels is screw up the cancer cells’ ability to adapt to the environment,” Denmeade says. “High amounts of testosterone are like an overdose. If you give prostate cancer cells too much, they can’t handle it,” Denmeade says. “They either stop growing or die.” In a 2021 study Denmeade co-authored in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, almost 80% of cancers responded to the high-low hormone cycling, as signaled by a 50% decline in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels.

Meanwhile, Donald P. McDonnell, a professor of pharmacology and cancer biology at the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina, has been on a similar mission to prolong the effectiveness of ADT by targeting the mechanisms in prostate cancer cells that spur tumor growth. In the Sept. 3, 2024, issue of Nature Communications, McDonnell and his research team shed light on how prostate cancer cells can have opposing biological responses to different actions on the same hormone.

“Our research lab found that cancer cells are hardwired with the ability to respond to two different doses of androgens,” McDonnell says. “With low androgen levels, the receptor in the cell is in one state, a monomeric form that drives the growth of tumors. With high androgen levels, the receptor is in another state, a dimeric state, which shuts down tumor growth.” McDonnell is working to develop drugs that lock prostate cancer cells into the dimeric state, which is what Denmeade and his team have been trying to achieve with high-low testosterone cycling.

“The treatment we’re using, a generic form of testosterone, is widely available, but what we still don’t know is the right way to do it,” Denmeade says. “More research is needed to determine the optimal BAT protocol and determine why it works in some patients, but not others.”

Still, Denmeade encourages patients with mCRPC to talk with their doctors about BAT.

“Everything says that BAT should be part of the standard treatment regimen, but one thing we don’t have is FDA approval because we haven’t done a large clinical trial,” Denmeade says. Nonetheless, BAT is catching on. In fact, Denmeade receives so many emails from patients around the world about BAT that he wrote a guide for patients to help explain this experimental treatment in plain language, which can be used as a conversation starter at oncology appointments.

“An important thing to keep in mind is that BAT is for men whose cancer is progressing on androgen deprivation therapy and who don’t have symptoms,” Denmeade says. Giving high dose testosterone to men with pain can make pain worse. “I’m enthusiastic about BAT, but I don’t want to oversell it. If it isn’t used correctly, it could also conceptually make cancer grow. We don’t see that, but I worry about it,” he says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.