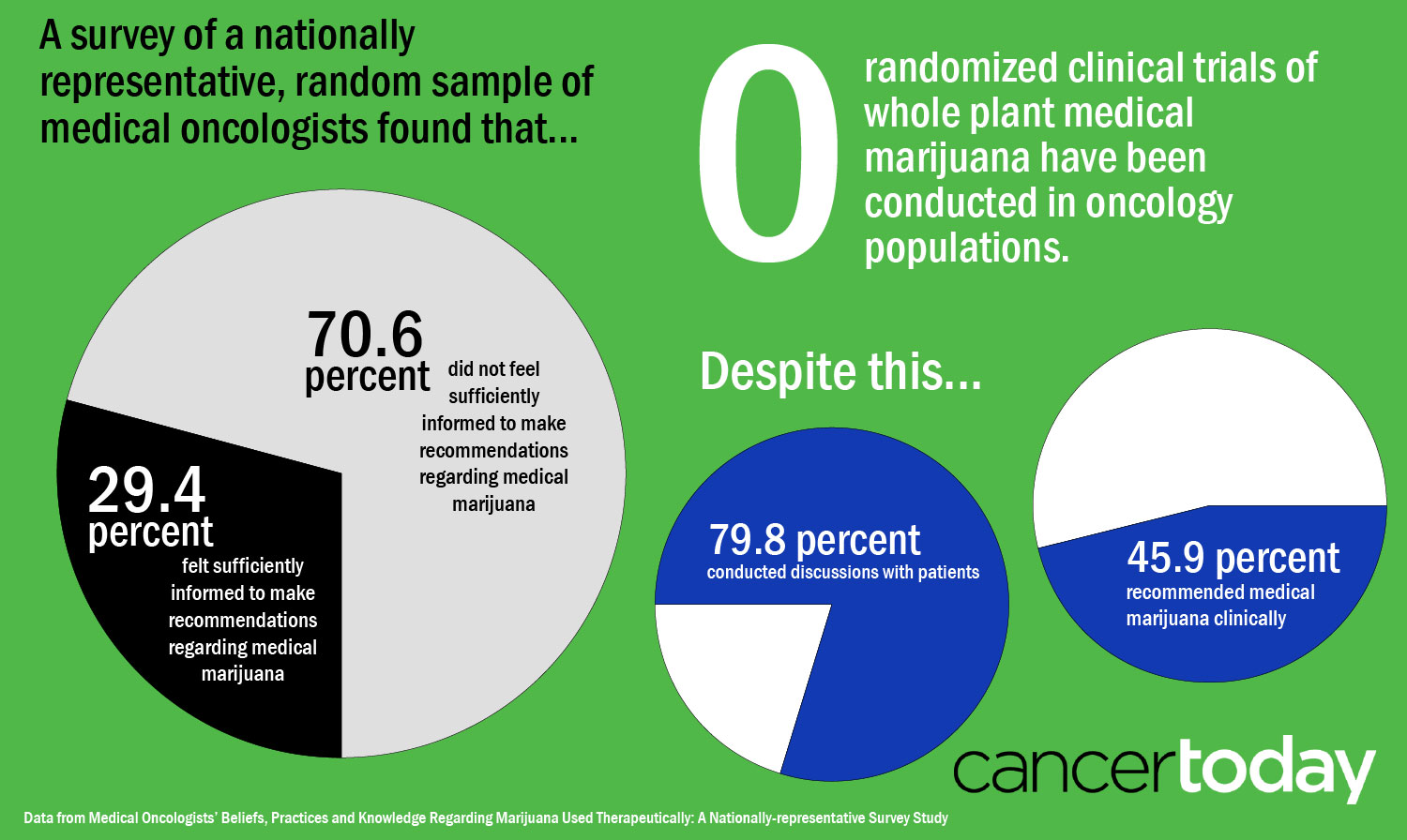

THE MAJORITY—AROUND 80 PERCENT—OF MEDICAL ONCOLOGISTS said they discuss medical marijuana with patients, according to a study published May 10 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology based on a survey of U.S. oncologists. Nearly half said they had recommended medical marijuana clinically in the past year. But despite this openness, around 70 percent of medical oncologists reported they don’t feel they know enough to make recommendations surrounding medical marijuana use.

“Oncologists on the whole don’t feel sufficiently informed about medical marijuana to make recommendations, but they are in fact recommending it,” says psycho-oncologist Ilana Braun, chief of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s Division of Adult Psychosocial Oncology in Boston, who is an author of the study.

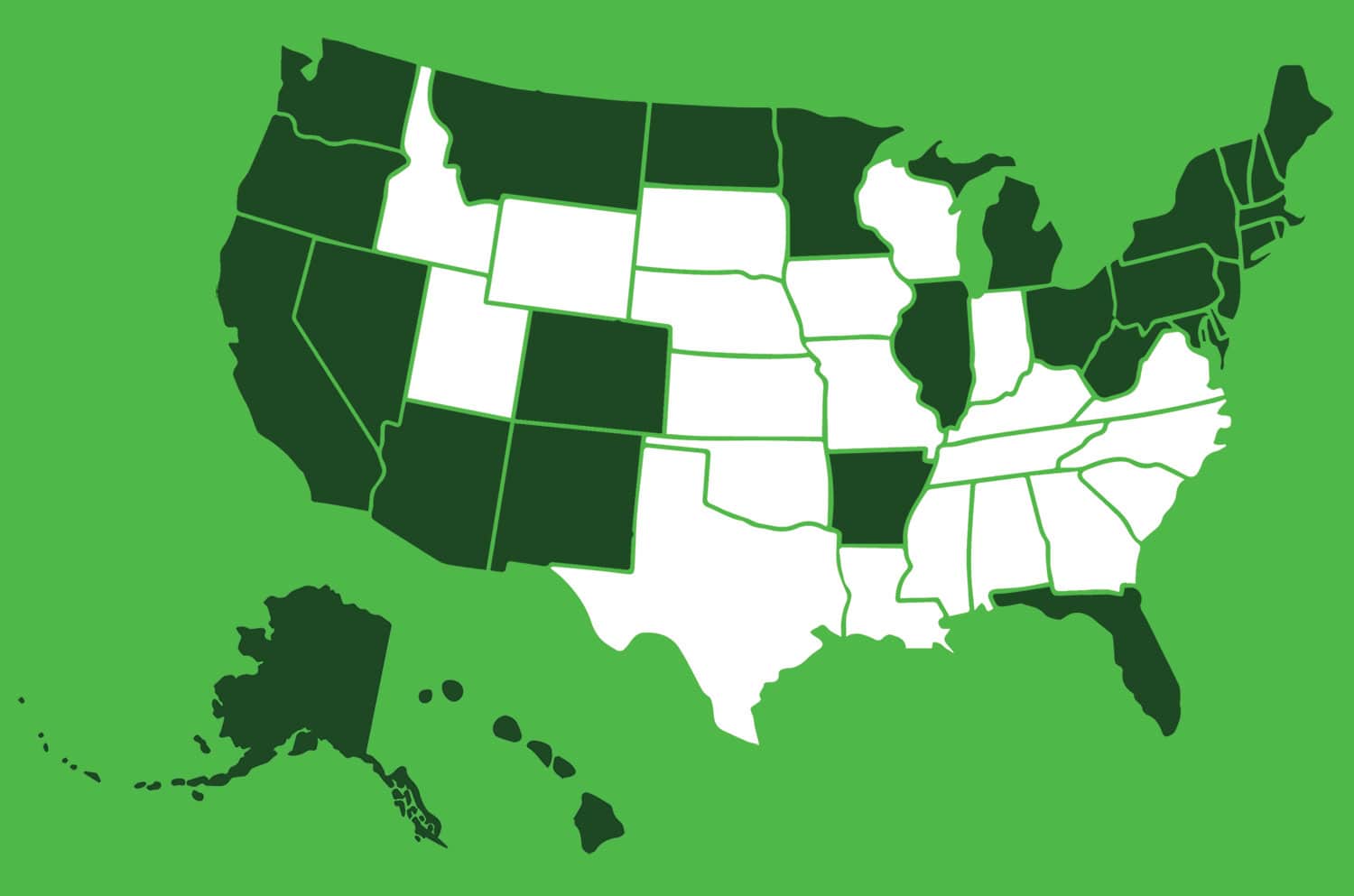

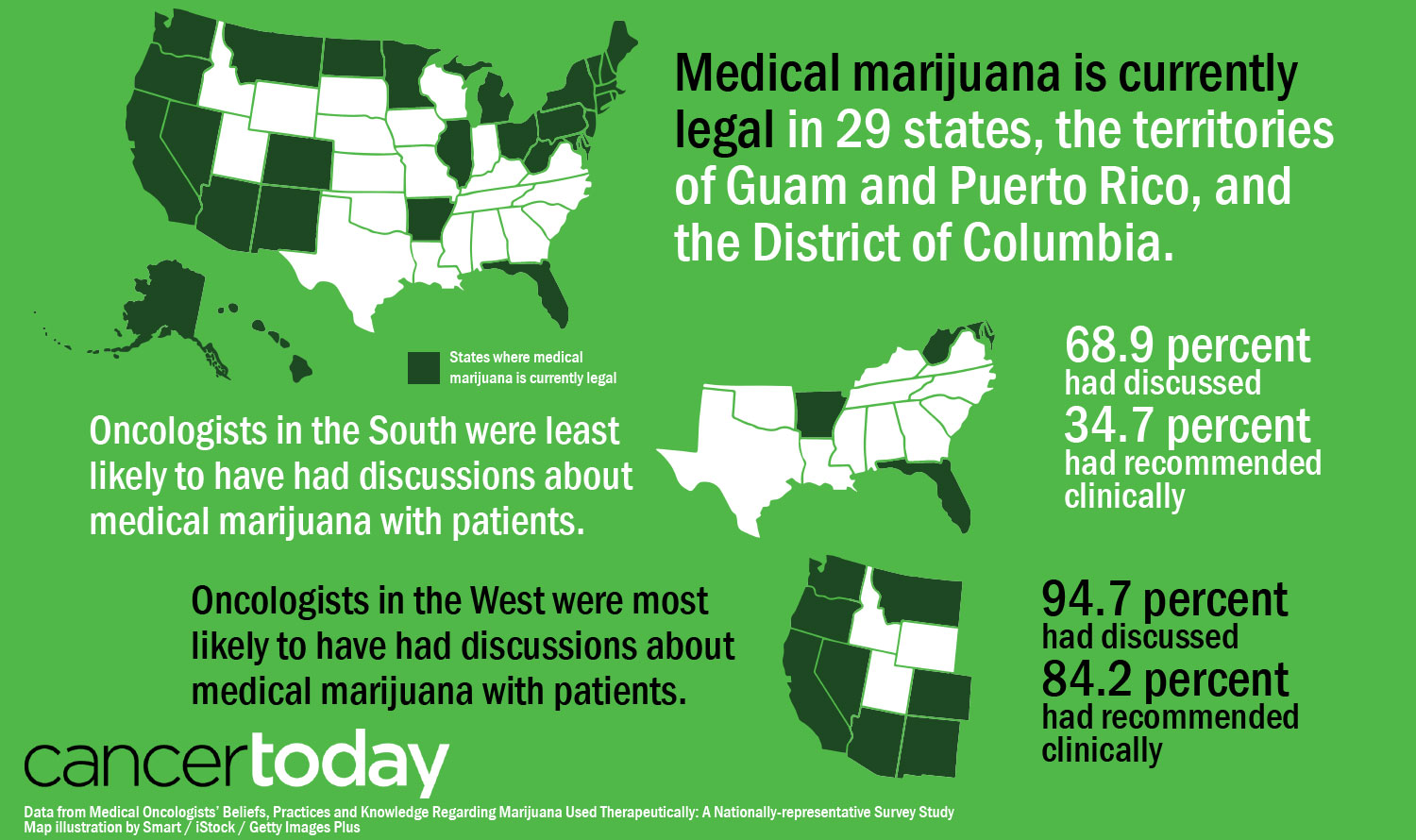

Braun and her colleagues based their analysis on surveys filled out by 237 medical oncologists. A little more than half of the oncologists were in states with medical marijuana laws. Across the U.S., 29 states and Washington, D.C., have laws allowing access to medical marijuana, but marijuana is illegal according to federal law. Among the oncologists who discussed medical marijuana with patients, 78 percent said that patients were the ones to bring up the topic most of the time.

The data show that patients are interested in talking about marijuana with their providers, says Steven Pergam, medical director of infection prevention at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, an associate professor at the University of Washington and an associate member at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. They also reflect the lack of information and training available for oncologists on the topic. “Normally, when we think about drugs we give patients, there is evidence that goes behind this … but in this particular arena there’s really a paucity of data to help us to determine what the real benefits are, and most of those data are not in populations that are specifically cancer patients,” says Pergam.

Pergam published a paper in Cancer in September 2017 finding that among patients surveyed at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance in Washington, 24 percent had used cannabis in the past year. Washington has laws allowing both medical and recreational use of marijuana.

In their paper, Braun and her colleagues point out that there have been no randomized controlled trials of whole plant marijuana in cancer patients. Oncologists are left to extrapolate from other sources of information. There are some small randomized controlled trials not focused on cancer patients indicating that whole plant marijuana can relieve pain, but there is “lower quality evidence” surrounding other uses of whole plant marijuana in cancer patients, such as to reduce nausea and vomiting, increase appetite and improve muscle wasting, the authors say.

Marinol (dronabinol), a synthetic compound similar to the marijuana component tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy that has not been treatable with other therapies. And studies have explored the use of other pharmaceutical-grade products that have highly refined and quality-controlled components of marijuana. But these drugs are “not easily comparable” to whole plant marijuana, which has hundreds of active ingredients, Braun says.

Braun’s survey also included questions seeking the oncologists’ views on marijuana’s efficacy for treating symptoms associated with cancer or cancer treatment. Braun and her co-authors say that the two-thirds of oncologists who said they supported marijuana as an addition to standard pain management strategies might be basing their views on the pain management trials in other types of patients. They might also view marijuana as less risky than opioids. Research indicates that opioid hospitalizations and deaths have fallen in states with medical marijuana laws. Braun and her co-authors expressed surprise that nearly two-thirds also saw marijuana as “equally or more effective than standard therapies” for low appetite and muscle wasting, given the lack of evidence in these areas.

Braun recommends that patients tell their oncology team if they are considering using or are already using marijuana. “It seems like, for the most part, oncologists will have an open stance.”

“I think it’s really important for patients and families to feel like it’s OK to ask about it, and to share,” says Prasanna Ananth, a pediatric hematologist-oncologist at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. “The vast majority of providers, I think, would want to know if their patient is using medical marijuana and wouldn’t admonish patients.” Ananth published her own study in Pediatrics in December 2017 showing that at three cancer centers in states with medical marijuana laws, 30 percent of pediatric oncology providers surveyed reported receiving inquiries about medical marijuana, and 92 percent expressed willingness to help children with cancer access medical marijuana.

Daniel Bowles, a medical oncologist at the University of Colorado in Aurora, says that patients have told him that they need fewer opioid pills in their prescriptions after starting to use marijuana. On the other hand, he says, he has helped patients realize when marijuana might not be helping. For instance, a patient with metastatic cancer started using marijuana extract hoping that it would treat his cancer, although there are not data supporting this. The patient developed a variety of problems including anxiety and low appetite. Bowles suggested that the marijuana could be contributing to these problems, and when the patient stopped using it, the problems went away.

Oncologists can also point out to patients when marijuana use might be particularly risky for them. Pergam says that marijuana could harbor mold and put patients at risk for infection, so he would recommend that a bone marrow transplant patient or another patient with a very weakened immune system stop using marijuana. Or if a patient had lung cancer and chronic lung disease and wanted to use marijuana, Pergam might suggest that they avoid smoking and use some other method of consuming it.

Patients need to realize that “the data is very sparse,” Pergam says. He advises caution in interpreting word-of-mouth advice or information resulting from general internet searches on marijuana, since something that seems to work for one person may not work for another.

Ananth adds that it’s important for patients to know that marijuana dispensaries are for-profit businesses that vary in their regulations and processes and generally “don’t carry medical expertise.”

Pergam says oncologists should not shut down conversations about marijuana. In his study in Washington, he and his colleagues found that nearly three-quarters of patients preferred to get information on marijuana from their cancer care team, but less than 15 percent said that they received marijuana information from this source. Lacking guidance from their care team, patients may get information from unreliable sources.

Instead, physicians should be upfront with patients about what they don’t know and what they know and work to help patients navigate marijuana use.

“I encourage cancer patients to partner with their oncology team to figure this out, even if it means figuring it out together in real time,” says Braun.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.