WHEN SHE WAS DIAGNOSED with metastatic breast cancer in 2018 at age 54, Katie Bushnell didn’t expect that one of her biggest challenges over the next 2 1/2 years would be getting to her appointments.

“I have to talk about life and death with my oncologist. That’s what I want to focus on, not how I’m going to get there,” says Bushnell, an advocate for improving access to medical care who lives in Sonoma County in the San Francisco Bay Area. She’s relocated several times in the past two years, with access to transportation at the forefront of her decision-making.

Katie Bushnell Photo courtesy of Katie Bushnell

Currently, the round trip from her home to the University of California, San Francisco medical facility where she receives treatment takes four hours out of her day. Although she has a car, Bushnell rarely feels comfortable using it—tumors in her spine have taken four inches off her height, making it difficult for her to see the road. The costs of maintaining and fueling the vehicle also quickly add up.

“For me to get to the hospital, I have to put in money for gas, the bridge toll and parking. It could be $50 just to get to my appointment,” says Bushnell.

Finding rides is often difficult, especially on busy weeks when she has as many as five or six appointments that may overlap with the work schedules of her friends and family. Services like Uber and Lyft are expensive, and public transit is unreliable at best. As an immunocompromised person, Bushnell also worries about the risk of exposure to the coronavirus.

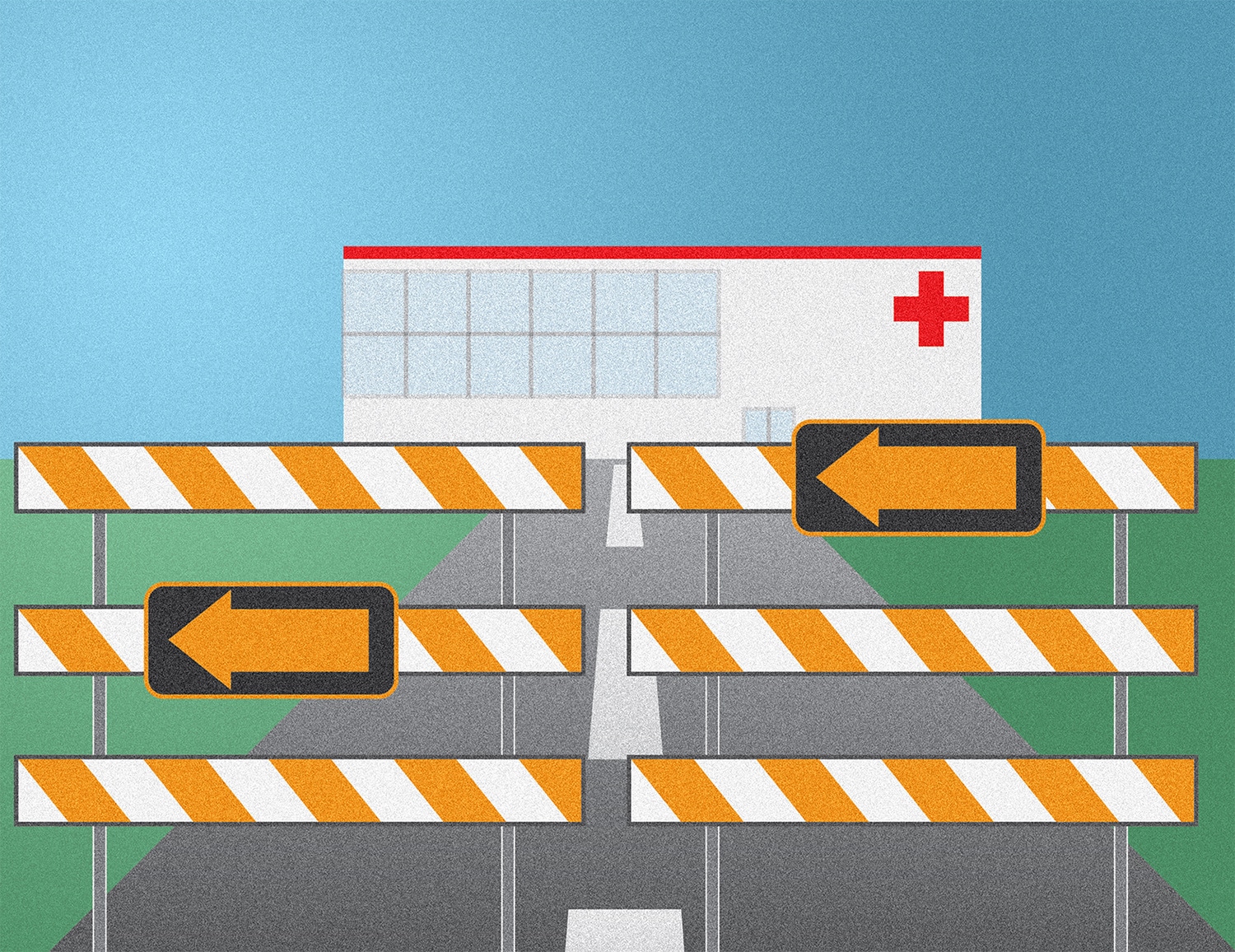

With a patchwork of transportation access that varies widely based on geographic location, medical condition, age and other factors, cancer patients often look to their communities and charitable foundations to fill in the gaps. But the pandemic has struck a blow to those options. In March, the American Cancer Society’s Road to Recovery program, which coordinated about 490,000 free one-way trips for cancer patients with volunteer drivers nationwide in 2019, was suspended.

“Cancer patients are an at-risk population for the virus. We realized that during this pandemic, we could not operate our Road to Recovery program in a way that was safe for patients and their families,” a representative from the American Cancer Society told Cancer Today via email. “Our hope is to eventually return Road to Recovery in a way that is consistent with safety guidelines and in keeping with our new financial realities.”

In June, the American Cancer Society announced that its budget was down 30% due to a decrease in donations since the pandemic began. It’s one of many charitable foundations affected.

In the past few months, charities that provide various types of financial assistance, including funds to cover transportation, medications and other expenses, have been less likely to have funds available, according to Ayesha Azam, the vice president of medical affairs at the Patient Access Network Foundation. Of the nine major charities that the Patient Access Network Foundation tracks, 36% are not giving out funds on any given day.

The Road to Recovery program has developed a reputation for being quick and reliable, able to coordinate rides in as few as several hours depending on the area, says Tiffani Hays, an oncology social worker at the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center in Lexington. Moreover, it lacks the often-restrictive eligibility criteria that shut out patients from other transportation programs, such as Medicaid’s non-emergency medical transportation program.

“That’s what’s been so upsetting about losing Road to Recovery,” says Hays. “It’s easy to use for patients and doesn’t require a social worker referral every time.”

Among those who have it, insurance doesn’t reliably offer a solution. Bushnell says she doesn’t qualify for transportation coverage as a Medicare beneficiary. Neither Medicare nor private insurance generally cover non-emergency transportation, although some Medicare Advantage plans may offer this benefit. Medicaid recipients may qualify for coverage to and from care that is proven to be a medical necessity, but requirements vary by state, and Hays says applying for this coverage can be tedious. The bigger challenge with Medicaid transportation, however, is that rides have to be arranged at least 72 hours in advance.

“If there’s a more emergent need, there’s a lot of red tape that you have to get through to get an approval,” Hays says.

In rural areas, where patients usually have to travel farther to access care, programs like Road to Recovery may not be enough to meet their needs. When she was living in Marin County, California, Bushnell says that it was difficult for her to arrange a ride in time for her appointment through Road to Recovery. In Fayette County, Kentucky, where Hays works, volunteer drivers are scarce.

As one of the most significant nonmedical expenses of cancer care—parking alone can cost more than one thousand dollars for a course of treatment—the cost of transportation can interfere with treatment. In a 2019 survey by the Pink Fund completed by nearly 800 breast cancer patients, over 60% of respondents reported that transportation barriers had caused them to miss or be late to an appointment. The Pink Fund pays bills—including car payments or insurance—for breast cancer patients who have lost income due to their diagnosis.

Read more coverage here from Cancer Today on the various impacts of the coronavirus on people with cancer.

Bushnell says she was overdue for her latest PET scan because of the hurdles she encounters in finding rides. “Sometimes I just don’t go,” she says. Bushnell estimates that she delays or misses appointments every three months. Recently, she’s been able to find rides with Pink Ribbon Girls, a nonprofit organization that provides food delivery, transportation and other services to patients with breast and gynecological cancers, which has her more optimistic about being able to make her appointments regularly.

Transportation barriers are just one of the challenges cancer patients face during the COVID-19 pandemic. In an American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network survey completed by over 2,000 cancer patients and survivors in August and September, 26% of all respondents reported having experienced delays in their cancer care since the pandemic began, often due to office or facility closures or concerns about getting COVID-19. Nearly a third of patients in active cancer treatment reported delays.

“Cancer treatment is expensive. It’s exhausting. It can be traumatizing,” says Fumiko Chino, a radiation oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City who studies the financial impact of cancer care, including the cost of parking. “And then there are all these other stresses patients have to deal with. It’s like adding insult to injury.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.