As chief executive officer and now executive chair of the Cancer Support Community, a global nonprofit network that each year provides more than $50 million in free support and navigation services to cancer patients and families, Kim Thiboldeaux estimates she’s talked to thousands of cancer patients. Across these conversations, “I’ve found that the themes, the questions, were oftentimes the same, reoccurring or were at least similar,” she says.

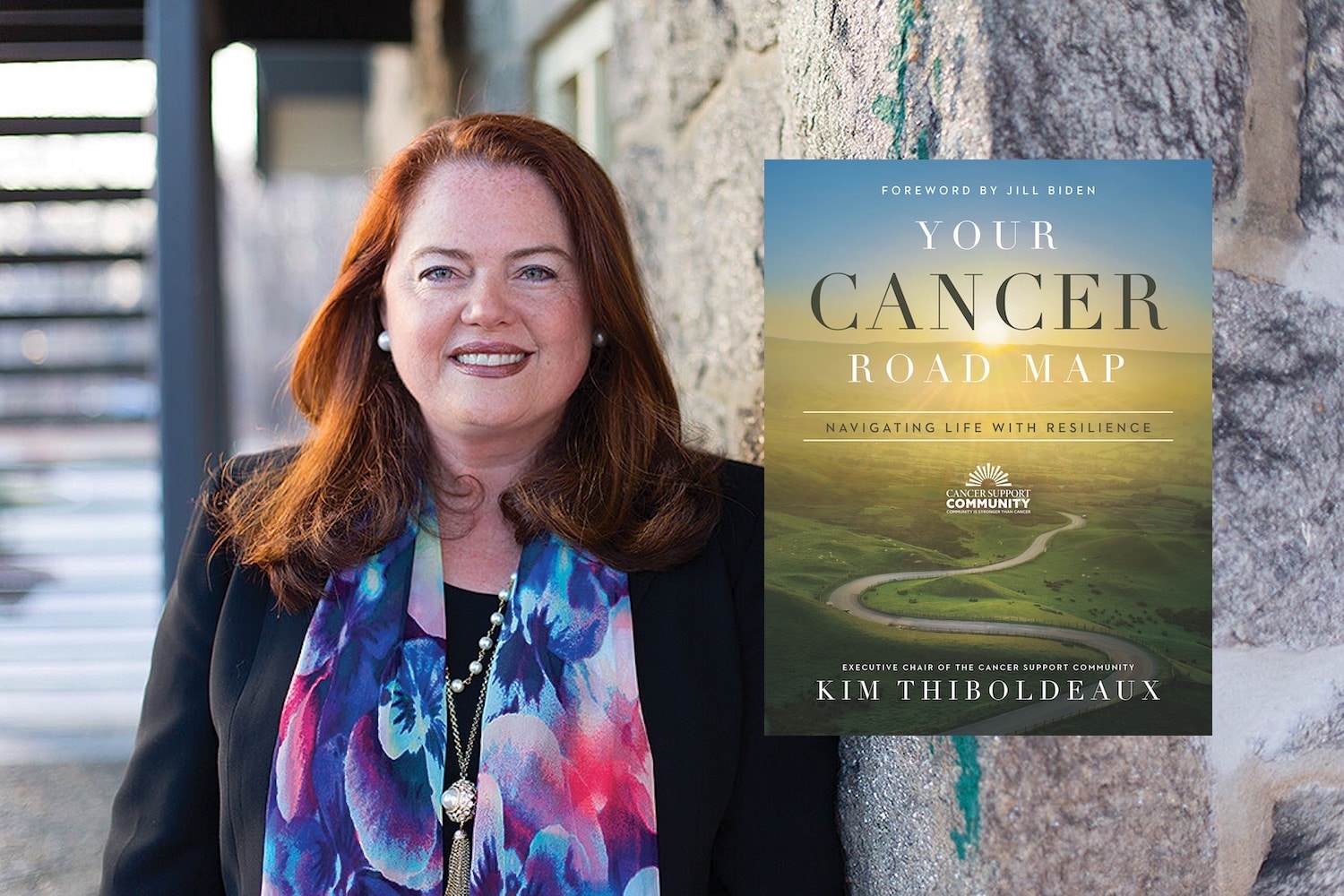

Drawing on these conversations, Thiboldeaux has written a new book, Your Cancer Road Map: Navigating Life With Resilience, that walks through the phases of cancer, from “Just Diagnosed” through “Active Treatment” to “After Treatment Is Done.” Thiboldeaux says that for patients, she wants the book to be “a resource to ease their journey, make it a little bit easier to get the answers they need, and to feel confident as they go forward when they face a cancer diagnosis.”

Cancer Today spoke with Thiboldeaux about the book and her advice on approaching a cancer diagnosis.

CT: In your new book, you say, “There isn’t a right way to take on cancer, there’s only the way that’s right for you. You’re in the driver’s seat and you will decide which route to take and how to choose to get to your desired destination.” What roadblocks might a person face that would prevent them from getting the health care they need?

THIBOLDEAUX: There are significant challenges and barriers in the health care system in the U.S. It’s a complicated and multilayered system. There are geographical challenges. We’ve seen a consolidation of cancer care—clinics and radiation oncology centers closing in rural parts of the country. We talk about the economic challenges of cancer. When somebody is diagnosed with cancer, I tell them, “Expect to go into debt. It is costly. Even if you have health insurance, you’re going to have a lot of out-of-pocket costs, copays. Perhaps you’re going to have lost income. You’re going to have child care costs or other costs that you may not be expecting and anticipating.” Many American workers do not have paid sick leave; they do not have health insurance or are underinsured. In the book we list many resources that address those issues. These challenges and barriers exist, but we want folks to know that they don’t have to face cancer alone.

CT: Someone who has a traditional view of the doctor-patient relationship might be told by their primary doctor that they’ll see a local oncologist. The patient doesn’t see beyond that or realize there are other possibilities. What would you say to a person like that?

THIBOLDEAUX: Tap into the resources available to you. If you have a good relationship with your primary care doctor, drill down on the questions and concerns and the barriers you have. If you don’t like the first doctor or oncologist you see, that’s OK. You can move on to another doctor where you feel a level of trust, and maybe to a doctor who looks more like you or has an understanding of your situation. We don’t tell people what they should do, but I want folks to make decisions with their eyes wide open. You need to tap into your own priorities and value system to make decisions that feel right for you and your circumstances, that feel right for your family.

CT: You devote a chapter to getting a second opinion. When and why would you recommend that to a patient?

THIBOLDEAUX: Some patients tell us they feel concerned about getting a second opinion because they’re afraid they’re going to offend their doctor or seem like a troublesome patient. No, no, no, no, no, no. Every patient has a right to a second opinion. There is a category of cancer centers called NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers, and often it makes sense to get a second opinion at one of those centers. We oftentimes find that when folks go to an academic center to get a second opinion, the doctors there may concur, and you can go back home to your doctor and get your treatment in your community. Also, the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial may open up to you. In general terms, health insurance will cover a second opinion.

CT: A very small percentage of patients participate in clinical trials. Why do you think that is? What would you say to a cancer patient who is interested in participating in a trial?

THIBOLDEAUX: If you were to ask people what a clinical trial is, many would say it’s a medical study where you either get the drug or you get the sugar pill, the placebo. It’s important for folks to know that almost no cancer treatment trials have a placebo. At a minimum, you will get the standard of care. Another misconception is that you’ll be treated poorly, you’ll be treated like a guinea pig, you won’t be respected. Data show that patients who participate in a clinical trial feel very well treated, very well cared for. We have made some progress in ensuring that many of the costs of clinical trials are paid for by insurance companies, but we need to face the reality that patients still may bear some out-of-pocket costs in clinical trials. Patients have expressed concern to us about logistical challenges of participating in a clinical trial, so we need to be doing a better job as a health care system in understanding and recognizing those barriers. There are many benefits to participating in a trial, not the least of which is you may have access to the next latest and greatest therapy.

CT: One of your 10 tips for living well with cancer is to get help from others besides your doctor. Why is that important?

THIBOLDEAUX: Cancer is an incredibly complex disease. It is expected that you’ll have a multidisciplinary team to help with your care. You may be dealing with a surgeon, a medical oncologist or radiation oncologist, but also other resources in the hospital, resources in the community, a social worker, the nursing staff, a financial counselor, nonprofit organizations in the community. If you’re a person of faith, rely on your clergy, rely on your faith community to support you through this illness. Tap into friends, neighbors, coworkers who want to be part of the team. You’re going to have a lot of folks who offer to help, and they’re sincere in those offers, so put them to work and tap into their expertise. If you want their help, have specific tasks to give to them.

CT: You have a long chapter in the book on side effects. Why are treatment side effects so important to patients or survivors?

THIBOLDEAUX: It’s important for a patient to understand, anticipate and track side effects and report them to their medical team. A lot of patients suffer in silence, which they don’t need to do. Oftentimes, the doctor can give you a holiday from treatment to rebound, or decrease the dose of your treatment to help manage side effects. Patients are afraid they’re going to be taken off a therapy, so they don’t report side effects. The issue of side effects links very directly to issues of quality of life, and quality of life while navigating a cancer diagnosis is really important to patients. Even though you’re on treatment, you still want to be able to do some of the things that feel right to you, feel good to you and feel normal to you. Side effects is an area where you can take some control. You’ll see chapters in the book where we talk about nutrition, exercise, and mind and body practices like meditation, relaxation and visualization, and guided imagery. Sometimes exercise can help you with fatigue. Many studies find that a little bit of exercise, even walking a few times around the dining room table, may be just the ticket for helping to address fatigue.

CT: You devote a chapter to finances and another one to health insurance. What can patients do to address the financial crisis in cancer care?

THIBOLDEAUX: Often patients are so in the fight to battle their cancer that they ignore financial issues or put them aside to deal with later. We encourage folks to ask at the hospital if there is a financial counselor, a financial navigator, someone in the billing department to speak about their financial struggles. Many organizations, like Cancer Support Community, offer financial experts. We have a financial counselor on our helpline who can help patients look at their insurance policy, help them with an appeal if something is declined by the insurance company. We offer free resources for financial navigation, as do many other organizations. There are nonprofit groups referred to as copay assistance foundations. If you have a big copay, you can apply for financial assistance. Many of the pharmaceutical companies also have navigators, nurses and other folks who can help you with finances if it’s related to their drug or medication.

CT: You talk about a survivor care plan in the book. What is that and why is it important?

THIBOLDEAUX: A number of years back, the Institute of Medicine put out a report on cancer survivorship, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. That report addressed the post-treatment phase of survivorship. It’s important that you, as an empowered patient, have a summary of your cancer patient experience, called a survivor care plan. What was the disease? What was the stage of the disease? Did you have surgery? What kind of surgery did you have? Chemo? What kind of chemo? How much? For how long? What were your side effects? Did you have medications to manage those side effects? And what is the medical surveillance plan going forward? How often do I go back? What kind of scans do I get? If I had a breast removed, do I still get mammography on the other breast? You will take the survivor care plan to your primary care physician, your cardiologist or your endocrinologist.

CT: What about end-of-life considerations when the treatments aren’t working and you’re not likely to survive the cancer?

THIBOLDEAUX: It’s a very personal decision to end treatment, and patients can really struggle with that decision. Or it could be the doctor who wants to keep trying because doctors are trained to cure. Maybe it’s the family. Patients tell me they feel guilty because they don’t want their family to think they’re giving up on them. So it is a tough decision—self-preservation is our most basic human instinct. But it’s an opportunity to tap into social workers, counselors or your faith community. Whatever your belief system is, how do you start to think about that as you plan for your death? It’s important to make sure all of your finances are in order and that you sort that out with your family. A lot of people think about the legacy they want to leave for their family, aside from financial resources. We see a lot of folks doing videos, writing letters, organizing pictures, making notes to talk about the lessons they’ve learned over their lives and the lessons and values they want to impart to their loved ones. It is sometimes hard for loved ones and family to let go and to support someone in making the decision to end treatment. But it’s important to really respect their decision and support that.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Click here to order Your Cancer Road Map: Navigating Life With Resilience.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.