Among the most frequent mutations that drive cancers are those in the KRAS gene, which controls cell proliferation. Identifying drugs that target KRAS effectively in patients has been challenging. But now, data from clinical trials with two different KRAS inhibitors demonstrate that these targeted therapies have the ability to shrink tumors in cancer patients.

Cancer Today spoke with Roy S. Herbst, a medical oncologist and lung cancer expert at Yale Cancer Center and Smilow Cancer Hospital in New Haven, Connecticut, about KRAS inhibitors and their potential for treating patients with cancer.

Q: What are KRAS mutations?

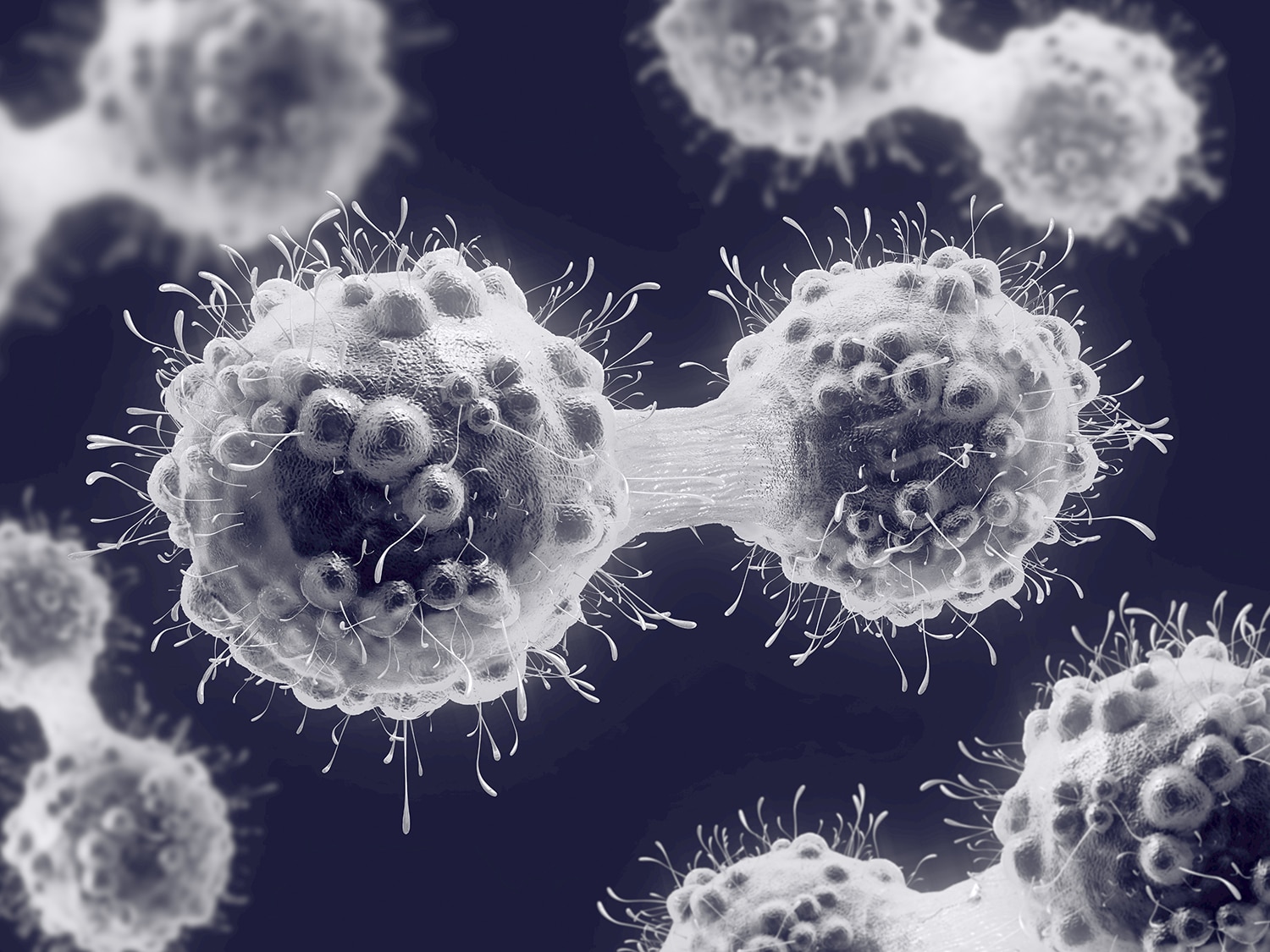

A: Cancer is driven by mutations that alter the growth of cells. One commonly mutated gene is KRAS, which encodes an important regulatory protein. When KRAS is turned on in an unchecked way, cells grow and divide abnormally. Mutations that turn KRAS on perpetually can lead to cancer, and that makes KRAS an oncogene, the most commonly mutated oncogene in cancer. KRAS mutations are often present in lung, colon and pancreatic cancers and a number of other tumor types. In lung cancer, for example, KRAS mutations are responsible for about 20% of tumors, and until recently, there has not been a way to effectively target the KRAS protein in cancer with drugs.

Q: Why is KRAS so difficult to target?

A: The KRAS protein is turned on when it binds to a molecule called GTP [guanosine triphosphate], which then activates cell growth and survival pathways. Mutations in KRAS that lead to cancer result in a KRAS protein that binds to GTP so tightly that the protein is in a perpetually activated state, and there have not been any drugs until now that could be designed to overcome this attachment. It has been considered to be an “undruggable” target.

Q: Which cancer patients are tested for the possible presence of a KRAS mutation and how does that guide treatment?

A: Some patients have been tested for the presence of a KRAS mutation routinely but nothing has been done to target this mutation because there were no drugs previously that targeted KRAS. Lung, pancreatic and colon cancer patients are tested for KRAS mutations, among other mutations. In colon cancer, the presence of a KRAS mutation means that the patient is not eligible for an EGFR inhibitor because the presence of such a mutation means that the EGFR inhibitor won’t work for that patient. In patients with lung cancer, the presence of a KRAS mutation means that the patient is unlikely to have an EGFR mutation, as these two mutations are usually mutually exclusive.

Q: Recently, a small molecule was developed called AMG 510 that specifically binds to a mutant form of the KRAS protein. This new drug has shown activity in lung cancer. Could you talk about the results?

A: There are different mutations that occur in KRAS. Among the most common ones in lung cancer is called G12C, which means that the 12th amino acid in the protein, a guanine, is mutated to a cysteine. This drug AMG 510 was developed to bind very well to this specific cysteine amino acid in the mutated KRAS protein. When AMG 510 binds there, it prevents the activity of the mutated KRAS protein. There is now some early data in patients showing clinical responses with this drug, and this is among the first KRAS inhibitors to show clinical activity in patients and not just in animal models.

These early results are exciting so far. The currently approved targeted therapies for lung cancer, such as EGFR inhibitors, are predominantly for those patients who have never smoked, but KRAS mutations in lung cancer are associated with smoking. For patients with KRAS who have a history of smoking, we have been using immunotherapies, which have an effect, but the responses have not been dramatic. We need new therapies. About 12% of non-small cell lung cancer patients have this KRAS mutation and could be eligible for this new KRAS-targeting drug, AMG 510. The early data so far show that seven of the 13 lung cancer patients with a G12C mutation who were treated with AMG 510 had tumor shrinkage, showing that attacking KRAS could be effective for this subset of lung cancer patients. The big question is whether these initial responses will be durable. We don’t know the answer yet.

Q: Are there additional KRAS targeting drugs that are in the clinic or are about to enter the clinic for cancer patients?

A: There is another KRAS inhibitor, MRTX849 from Mirati Therapeutics, that also targets the G12C mutation, and the data so far are similar to the AMG 510 data, where about half of the KRAS G12C lung cancer patients respond to the therapy.

Q: Aside from duration of response, what are the remaining questions about these potential new drugs?

A: A major question is whether and when resistance could emerge when a patient is treated with AMG 510 and with other KRAS inhibitors. Other questions are whether this drug and other similar drugs will be active in the brain, what their effect on the immune system might be, and whether they will work on their own or will work better in combination with another drug. There is also the question of whether these drugs might work in other tumor types that harbor KRAS mutations, such as colon and pancreatic cancers. We need a lot more preclinical and patient data to figure out these questions.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.