Adriana Ford does not consider herself an artist. But last year, the London-based environmental scientist and breast cancer survivor participated in a project run by Cardiff University, Wales, in which cancer patients created works of art relating to their cancers. Ford, who was diagnosed with stage IIIC breast cancer at age 34 in 2016, found the experience of painting the resulting artwork, Healing with Gold, “quite therapeutic and cathartic.” Then in October 2017, to give others a chance at a similar experience, Ford founded the Breast Cancer Art Project, a website showcasing art by breast cancer patients and survivors.

In the half year since the project’s founding, it has featured more than 100 works by 30 visual artists and poets. Ford accepts all submissions, in all art forms, as long as the works meet three criteria: Their contributors have or have had breast cancer; they relate to breast cancer in some way; and they are in formats that can be displayed online.

Contributor Susan Olivera, who was diagnosed with stage III breast cancer at age 32 in 2007, says that those with cancer often need to express themselves in some way about their experiences. “Some people write; some people just tell the story a lot, for groups and stuff.” But retelling one’s cancer story “can be a little bit draining,” says Olivera, who lives in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. Through art, people can tell their stories “in a different way, in a creative way,” she says, and in the process express emotions that words cannot.

“What’s really important for me is for the project be inclusive, for anybody to feel that they can submit something,” says Ford. “I encourage people who haven’t picked up a pencil or used their creativity, maybe even since they were kids, to give it a go.” To encourage people who want to contribute but also would like some art guidance, Ford recently established a program in which artists volunteer to mentor would-be contributors by email or phone.

“[Ford] has been very generous in how she promotes all of us amateurs,” says contributor Annie Dennison of Aliso Viejo, California, who was diagnosed with stage IIA breast cancer at age 53 in 2015. “Most of us are not professional artists. We have been professional breast cancer patients, and then we take on art, and it is salvation for a lot of us.”

Ms. Pretty Scared is part of Annie Dennison’s series Barbies Losing It.

Dennison, a retired clinical psychologist, had enjoyed both photography and creating mixed-media art before she was diagnosed with breast cancer, but the diagnosis spurred her to pursue art more intensely, she says. Chemotherapy left her too sick to go out and take pictures, so she looked for something that she could photograph at home. Then she got an idea: to take Barbie dolls, pull out their hair to simulate chemotherapy’s well-known side effect, and then dress, pose and photograph them. The Barbies Losing It series was born.

To take one example: For Ms. Pretty Scared, one of several photographs from the series, Dennison began with a Barbie in a T-shirt with the word “pretty” across the chest, then digitally added the word “scared” below. Many women dislike Barbies, Dennison says, because they represent idealized and often unattainable feminine beauty. “I kind of wanted to turn that on its head,” she says. “Yeah, pretty’s nice. It can be good. But most importantly, we are pretty scared. … And it’s also this concept that for some women who have cancer, especially if they’ve had mastectomies, that they’re still beautiful. They’re still beautiful, but they are scared. They’re both.”

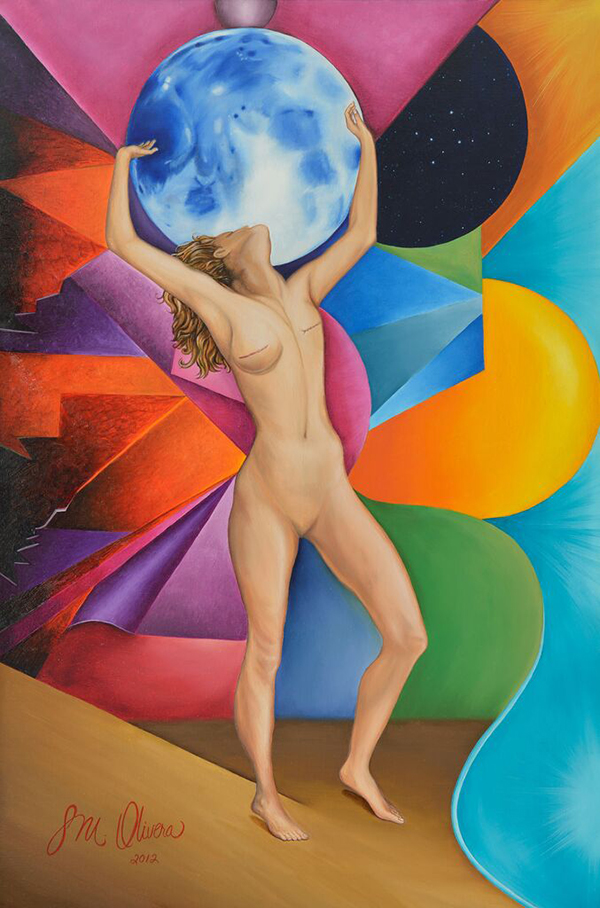

Susan Olivera painted Sobrevivi as she was starting to feel better after years of sickness

Olivera also felt compelled to make art after her experience with cancer. Following years of sickness, in 2012, she started to feel better and, on a psychologist’s suggestion, took an art class. There she did her first oil painting: Sobrevivi, which translated from Spanish means “I Survived.” The painting depicts a nude woman with scars on both breasts standing, as Olivera describes it, in a victory pose under a backwards moon. The colored fragments on the woman’s right side represent the chemotherapy sessions and surgeries that Olivera underwent.

In the years following the class she painted more and more. Now Olivera—who already had degrees in biology and medical technology—is in her third year of studying for a B.A. in fine arts at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez. “I wouldn’t have considered it before cancer,” she says. “[The cancer] was like, I don’t know, gasoline, a very particular way of getting the motivation to do something.”

In the future, Ford hopes that the Breast Cancer Art Project will be able to offer free art workshops to cancer patients and survivors as well as hold brick-and-mortar exhibitions. “There’s lots of scope to take things further,” Ford says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.