UTERINE CANCER RATES have increased in many countries, including the U.S. This increase has often been attributed to the rise of obesity, as obesity raises the risk of the most common form of uterine cancer.

A study published May 22, 2019, in the Journal of Clinical Oncology challenges the idea that obesity is largely to blame for rising uterine cancer rates, however. Instead, increases in a particularly aggressive form of uterine cancer that is less linked to obesity are driving the rise in uterine cancer incidence overall. Further, the study shows that uterine cancer rates have increased the fastest in women who are Hispanic, Asian or black.

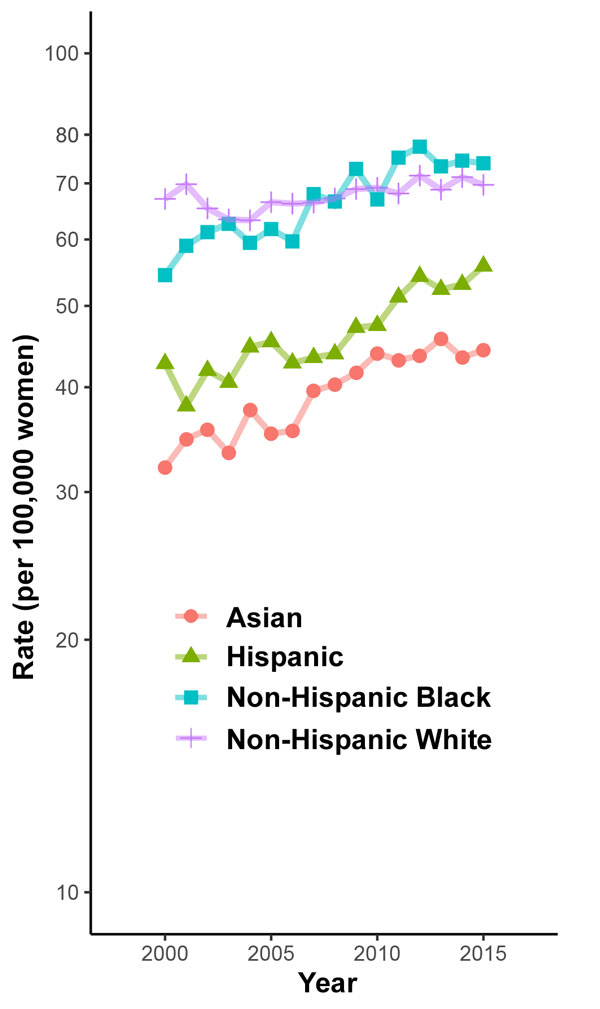

Rates of uterine cancer have risen in Asian, black and Hispanic Americans. Data source: ‘Hysterectomy-Corrected Uterine Corpus Cancer Incidence Trends and Differences in Relative Survival Reveal Racial Disparities and Rising Rates of Nonendometrioid Cancers,’ Clarke et al.

Researchers examined data from 2000 to 2015 from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), which compiles and analyzes data from cancer registries nationwide. Unlike some previous studies, the new study included a correction for the prevalence of hysterectomies among various groups, since a woman whose uterus has been removed cannot get uterine cancer.

The researchers found that although the rate of uterine cancer did not rise significantly from 2000 to 2015, the rate increased by around 1% per year from 2003 to 2015.

The researchers also looked at incidence of various uterine cancer subtypes. Most uterine cancers start in the endometrium, or uterine lining. These cancers are classified by their histology, or appearance under the microscope, as belonging to either endometrioid or nonendometrioid subtypes.

Endometrioid cancers make up the majority of endometrial cancer cases, and their incidence remained steady overall from 2000 to 2015. The rate of nonendometrioid cancers increased overall during this same period.

Endometrioid cancers develop and grow in response to estrogen. Obesity increases estrogen levels. That’s why both obesity and other hormone-related factors, such as taking estrogen without progesterone during menopause, are risk factors for endometrioid cancers, explains Rebecca Arend, a gynecologic oncologist at University of Alabama at Birmingham, who was not involved in the study. “The more estrogen that is in your body, the more likely it is for this cancer to develop,” Arend says.

Nonendometrioid cancers are more aggressive and come with poorer prognoses. The association between nonendometrioid cancers and hormone-related factors like obesity is less strong, the authors note in their study.

“Because our data show stable rates of endometrioid cancer but these rapidly increasing rates of nonendometrioid cancer, it suggests to us that it can’t be just obesity that’s causing these trends, because otherwise we would expect to also see an increase in the endometrioid types,” says study co-author Megan Clarke, who is an NCI research fellow in Rockville, Maryland. “It suggests to us that there’s perhaps risk factors that we’re not completely aware of, or that we don’t fully understand, that [are] really driving the specifically high rates and increases in the nonendometrioid types.”

The researchers also looked at how uterine cancer incidence varied by race and ethnicity. At the beginning of the study period, in 2000, white women had the highest rate of uterine cancer of all racial or ethnic groups. In 2007, the incidence of uterine cancer in black women first surpassed that in white women. After 2011, incidence remained consistently higher in black women than white women for the rest of the study period.

Hispanic and Asian women had the lowest absolute incidences of uterine cancer of the racial or ethnic groups studied. However, the uterine cancer rates rose the most rapidly in these groups. The uterine cancer rate did not increase significantly in white women over the study period.

Data source: ‘Hysterectomy-Corrected Uterine Corpus Cancer Incidence Trends and Differences in Relative Survival Reveal Racial Disparities and Rising Rates of Nonendometrioid Cancers,’ Clarke et al. / Graphic by Bradley Jones

“It used to be that uterine cancer was a predominantly white cancer, and that is now changing,” says study co-author and NCI researcher Nicolas Wentzensen. The researchers say they do not know what is causing these racial and ethnic differences in cancer rates.

The researchers found that black women had the highest rate of nonendometrioid cancers. Black women also had the lowest uterine cancer survival rates of all races or ethnicities, regardless of cancer subtype or stage at diagnosis.

In order to understand why nonendometrioid cancers are rising so dramatically and to address related racial disparities, it will be necessary to learn more about risk factors and exposures related to that subtype, the researchers say.

“The nonendometrioid subtypes have been more rare, and so they’ve been more historically difficult to study just because we don’t have the numbers,” Clarke says.

Understanding uterine cancer better will also require researchers to include participants from diverse groups in their studies. For instance, Wentzensen is currently studying early detection of endometrial cancer via DNA found on tampons. Early studies of this method included primarily white women. He is currently running a study that he anticipates will include a large proportion of black participants.

“There are efforts to increase the participation of non-Hispanic black women in these studies and really understand the differences by race and subtype and evaluate potential causes of the cancers,” Wentzensen says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.