CANCER PATIENT ADVOCATES take on many roles in their communities. They may go out to churches to promote the benefits of cancer screening, lead patient and survivor support groups, either in-person or online, or offer a patient’s perspective on review panels that evaluate research grants. Many times, an experience with cancer pushes people to accept advocacy roles to fill some unmet need, or simply to give back.

All of these efforts were on display at this year’s American Association for Cancer Research Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved in New Orleans Nov. 2-5. Opening the conference, 10 patient survivors and caregivers of various ethnicities and types of cancers took to the stage to describe how cancer has changed them and what cancer research has given them personally.

“I’m here today to voice my commitment to have more people who look like me in the fold for research and investigation and for medical science,” said Winona Hollins Hauge, an African-American patient advocate who has worked as an outreach manager for Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle and who took care of both of her parents when they had colorectal cancer. Diane Nathaniel, a four-year colorectal cancer survivor living in New York City, started an advocacy group called Beat Stage III to help spread awareness. “Cancer research has allowed me to go to medical school and start an advocacy organization,” she said to the hundreds of attendees at the opening session.

Hollins Hauge and Nathaniel were two of 19 patient advocates who attended the conference as part of the Scientist↔Survivor Program (SSP), an initiative that brings together survivors and scientists to learn from one another. In addition to learning about the latest findings at the disparities conference, patient advocates also attended mentoring sessions with researchers, discussed their advocacy efforts as part of the scientific poster presentations, and learned about cancer research in classes geared toward advocates.

Patient advocate and metastatic breast cancer survivor Sheila McGlown talks with fellow participants in the Scientist↔Survivor Program. Photo by © AACR/Todd Buchanan 2018

The conference analyzed current research on cancer health disparities, scrutinizing the gaps between rich and poor, various ethnicities and whites, and people who live in rural and urban areas. The meeting included presentations on genomic testing, financial toxicity and technologies and approaches to increase clinical trial participation.

“For me, it was impressive that [researchers] were even addressing disparities in an environment like this. This is what advocates have been saying all along, that there are racial disparities, and they are actually addressing it. And now I can take that back into my community,” said Sheila McGlown, a 52-year-old African-American woman who was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer in 2009 at age 43. McGlown is a patient advocate with the St. Louis Breast Cancer Foundation and participated in SSP training.

Advocates, for their part, remained resolute to help ensure health care reaches all corners of their communities, by spreading the word about cancer screening, new treatments and the importance of clinical trials.

“My doctor didn’t have to convince me [to enter the clinical trial] because I have that physician-patient relationship,” said McGlown, who enrolled in a clinical trial in July for a chemotherapy and targeted therapy combination—despite having other standard-of-care treatment options.

McGlown’s disease has stabilized on the combination therapy. “My thing is, if I am going to talk the talk, I’m going to walk the walk. I want to show people. These are life-saving drugs.

“You have 100 people in a clinical trial, and five people are black,” she continued. “That’s not a cross-section of the breast cancer community. We need to get involved, and we need to get away from the stigma that they are using us as guinea pigs. We talk about Henrietta Lacks or the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. We need to get away from that.”

The Patient Voice

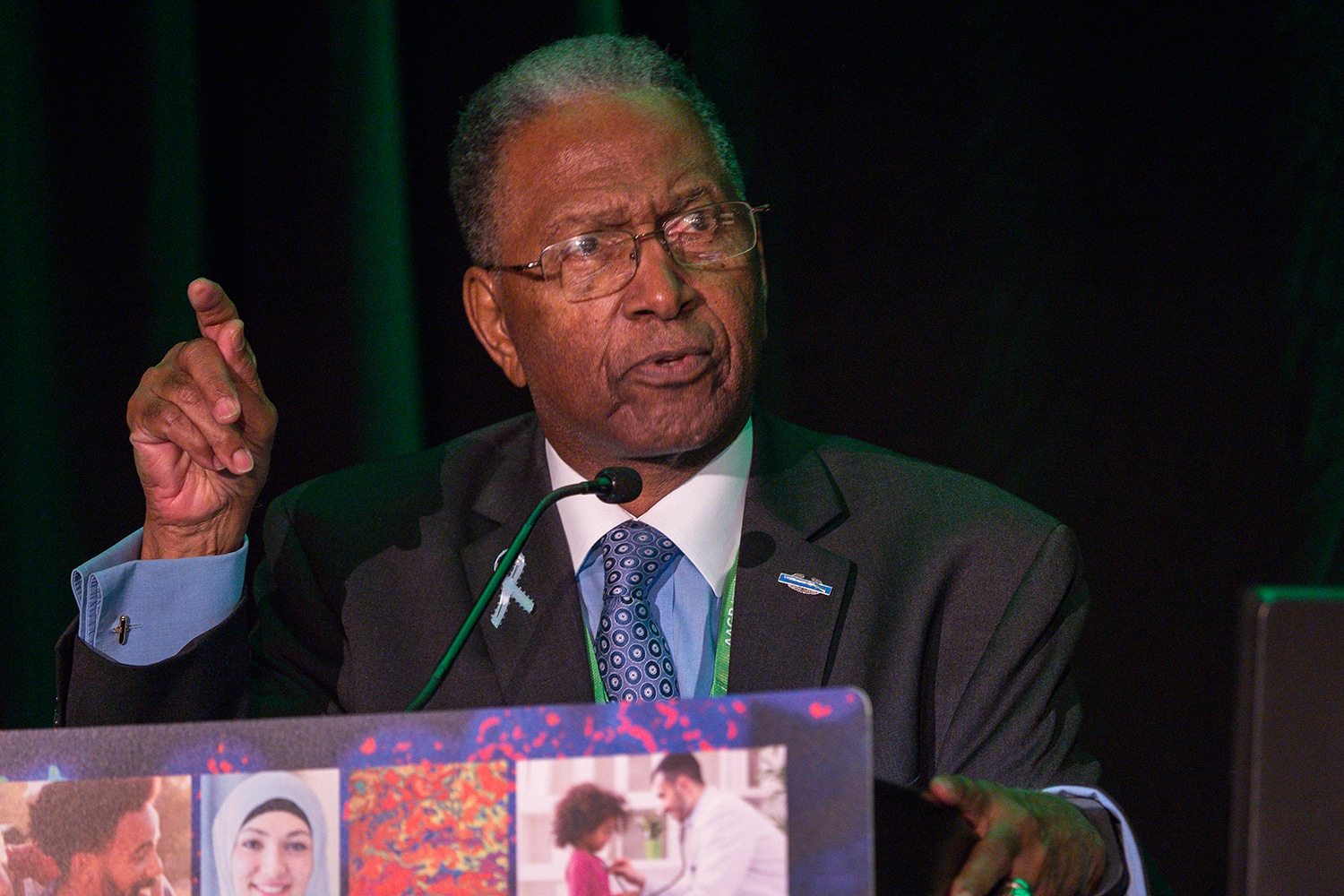

Advocates also made presentations alongside researchers as part of the scientific program—in addition to presenting posters. One advocate, Jim Williams, a 19-year prostate cancer survivor and an alumnus of SSP training, explained the difficulty of his work, and the power of having people in the community promote the benefits of screenings. This is particularly true for African-American men, he said, who are at higher risk of developing prostate cancer, are more likely to die from the disease, and often don’t want to talk about their health, he said

“This is hard work. This is one on one. I go to men and say, ‘How’s your prostate?’ [And they say,] ‘Wait, I don’t know you.’ But that’s how you start your conversation,” said Williams, who discussed health care barriers in minorities during an educational session. The retired Army colonel, who served in Vietnam, drew an analogy from his military training: “In the military, with all our sophisticated weapons today, we don’t really own that geography until we plant the flag. And who are the people that plant the flag in the ground? It’s ground cavalry and infantrymen. It’s not the guy in the fancy airplane. It’s not the guy with the electronic devices. It’s the soldier on the ground planting the flag. That’s what we need to do, we need to plant our flag in the community.”

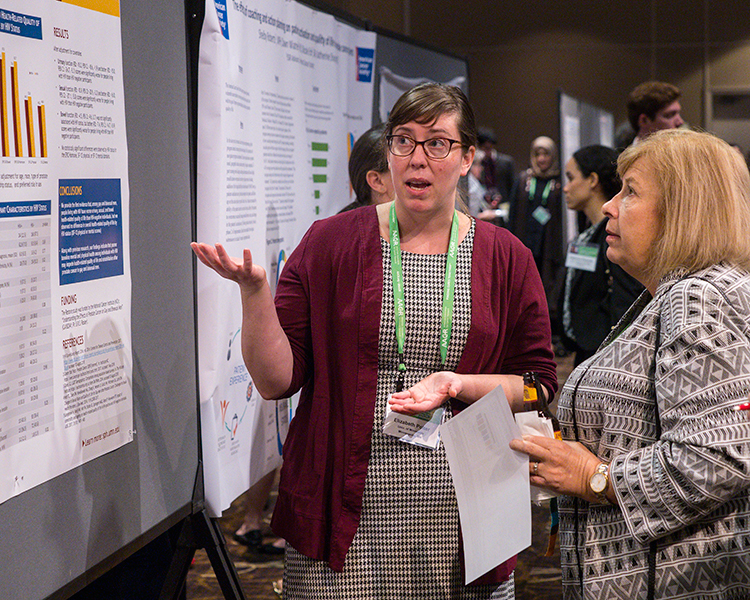

Multiple myeloma survivor and patient advocate, Cindy Chmielewski, on right, stops to talk with Elizabeth Polter, a graduate research assistant at the University of Minnesota, about her research. Photo by © AACR/Todd Buchanan 2018

Advocates were figuratively staking flags in various ways—solving problems unique to their environments and culture. Althea Bailey, who works as an outreach advocate for the Centre for Research Excellence in Jamaica, is aiming to increase the rate of cervical cancer screenings in her country. She discussed cervical cancer in Jamaica as part of her poster presentation. Jamaica has the capacity to screen more than 350,000 women each year for cervical cancer, she said. Still, only 30,000 women are tested for cervical cancer annually. She explained the stigma associated with screening and another barrier: It takes six months for patients to get results from Pap tests. “It’s devastating that they have to wait that long,” she says, noting that cervical cancer is a preventable disease with Pap testing to detect precursor lesions.

The 2018 AACR Scientist↔Survivor Program for the AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved included 10 cancer survivors and two caregivers. Pictured above from left, top row: Rebecca Esparza, Ovarian Cancer Research Fund Alliance; Marisel Brignoni, Dot4Life; Cindy Chmielewski, independent advocate; Althea Bailey, Centre for Research Excellence; Fred Hardy, Karmonos Cancer Institute; Susie Brain, UCSF Athena Breast Health Network; Kimberly Richardson, independent advocate; W. Erika Nalls, independent advocate; Anneliese Wilson, Pancreatic Cancer Action Network; Jennifer Elliott, independent advocate; Chiara D’Agostino, SHARE Cancer Support and Beauty through the Beast; Mike Lawing, KCCure; Carrie Treadwell, American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). Bottom row, from left: Sheila McGlown, St. Louis Breast Cancer Foundation; Winona Hollins Hauge, Intercultural Cancer Council Regional Network; Karen Russell, AACR; Virgie Townsend, independent advocate; Beulah Brent, Sisters Working It Out; Wenora Johnson, Fight Colorectal Cancer; Diane Nathaniel, Beat Stage 3 Inc.; Lou Lanza, independent advocate. Photo by © AACR/Todd Buchanan 2018

Beulah Brent, an African-American woman who lives in Matteson, Illinois, handles community outreach for an organization called Sisters Working It Out. The organization trains 12 volunteers each year to go out and spread the word about breast cancer screening at churches and other places in the community. The organization also helps to arrange transportation to and from hospitals for mammography appointments. Participating in SSP has led Brent to think about expanding her program—to not only train 12 women a year, but to train them to train other women to espouse benefits of cancer screening. “You can educate 12 women, but we can educate them to educate others and reach more than 100,” said Brent, who learned about this approach at the conference through an SSP presentation by Beti Thompson, a researcher at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“You know communication is really the key for everything. And to be able to learn and see what the scientists really do [helps inform that],” says Brent. “Knowledge is always better. And what are you going to do with it? I take the knowledge and I am so excited about it. I’m about to share what I’ve learned.”

Note: The deadline to apply for the next Scientist↔Survivor Program at the AACR Annual Meeting is Dec. 11, 2018. The AACR Annual Meeting will take place March 30-April 2, 2019 in Atlanta.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.