WHEN HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS are faced with decisions about whether a therapy is likely to benefit a cancer patient, they often refer to a metric known as performance status—a measure of a patient’s general well-being and activity level. A patient’s performance status can offer insight into the likely outcome of treatment. For example, research has shown that patients with poor performance status who receive chemotherapy have a reduced chance of survival and worse quality of life.

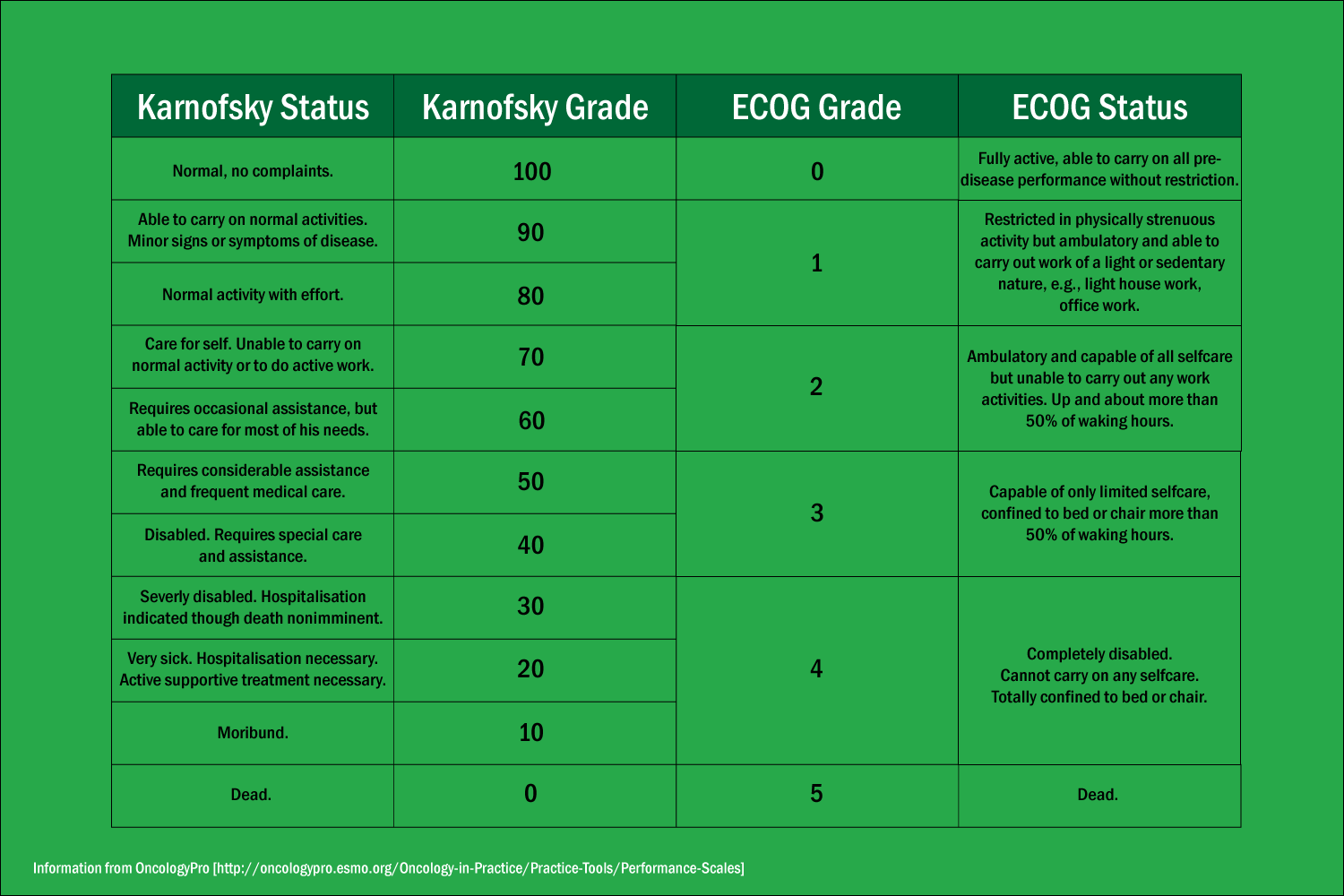

Performance status can be useful, but it’s not a perfect measure. The two most commonly used scales—the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), which was first described in 1948, and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status, first published in 1982—both rely on patients to respond accurately to questions about their activity and on their doctors to correctly interpret this information and assign scores to the patients.

Researchers are now suggesting that physical activity monitors could provide less subjective information on how patients function in their day-to-day lives. These monitors—which include Fitbits and Apple Watches—can provide information on activity including sleep quality, steps taken per day and heart rate.

“Everybody has had a situation where you ask a patient, ‘How are you doing? How is the chemotherapy treating you?’ and the patient will put a brave face on and they’ll say, ‘I’m doing fine,’ and you spend 20 minutes to try to understand what ‘fine’ means,” says Muhammad S. Beg, a medical oncologist and the medical director of clinical research at the UT Southwestern Medical Center’s Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center in Dallas. When the doctor finally starts to think she has a good sense of the patient’s well-being, says Beg, a family member usually chimes in and says that the patient is either understating or overstating their problems.

Beg published a study in JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics on April 30 assessing the feasibility of using wearable activity monitors to help determine the activity and functional status of cancer patients. Beg and his co-authors had 24 patients with cancer use a Fitbit Flex physical activity monitor for 12 weeks. All but one of the patients wore the monitor more than half the time and 19 patients wore it on more than 70 percent of days. Three-quarters of patients reported a positive experience using the technology.

The most basic implementation of wearable devices would be to record a patient’s step count. Beg’s study found that patients with an ECOG performance status of 0 (which refers to someone able to live normally with no complaints) recorded a median of 5,911 steps per day. Those with an ECOG performance status of 1 (which is described as someone who cannot perform physically strenuous tasks but is otherwise active) recorded a median of 1,890 steps per day, and those with an ECOG performance status of 2 (capable of self-care but not work) recorded a median of 845 steps per day.

A comparison of the Karnofsky and ECOG scales.

Beg was pleased to see that daily step counts correlated with ECOG performance status scores, but he still has criticisms of the performance status method, which he describes as “archaic.” He compares it to a long-outdated method of measuring the levels of hemoglobin in the body by looking under the eyelids and gauging the paleness of the conjunctiva. To him, the situation is similar—instead of taking an objective measurement, doctors are relying on anecdotal evidence.

When health care providers make their performance status assessment, they’re forced to base their judgment on a relatively narrow view of their patient. The patient might be having a particularly good day or a particularly bad one. Incorrect ratings could change a patient’s eligibility for a clinical trial or alter the treatment course.

But Gillian Gresham, a postdoctoral fellow at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said in an email to Cancer Today that, for now, wearable technology is better suited to a supplementary than a primary role in determining performance status. Gresham authored a paper about the use of wearable activity monitors in oncology trials published in the January 2018 edition of Contemporary Clinical Trials.

Gresham notes that quality of life is difficult to assess, and an objective reading from a wearable device might not give a broad enough insight. Her study did not find correlation between sleep duration and frequency measured using an activity monitor and patient’s own reports of their sleep quality, for example. However, the activity monitors did corroborate the reports of patients who said they were more active and more able to move around. And patients’ reports of their pain, fatigue and overall well-being correlated with step counts and the number of stairs they had climbed in a given day.

“An ideal measure of quality of life may therefore include a combination of objective physical activity and functional assessment with the activity monitor in addition to patient-reported symptoms and quality-of-life through a mobile app,” Gresham said.

In the nearer term, having records available from wearable devices might help health care providers monitor patients’ condition on an ongoing basis. “Let’s suppose that grandma has a Fitbit, and we’re noticing that grandma always used to do four or five thousand steps, and for the last two weeks, she’s down to one hundred,” explained Beg. “That could trigger some type of an alert to the system, to check in on grandma.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.