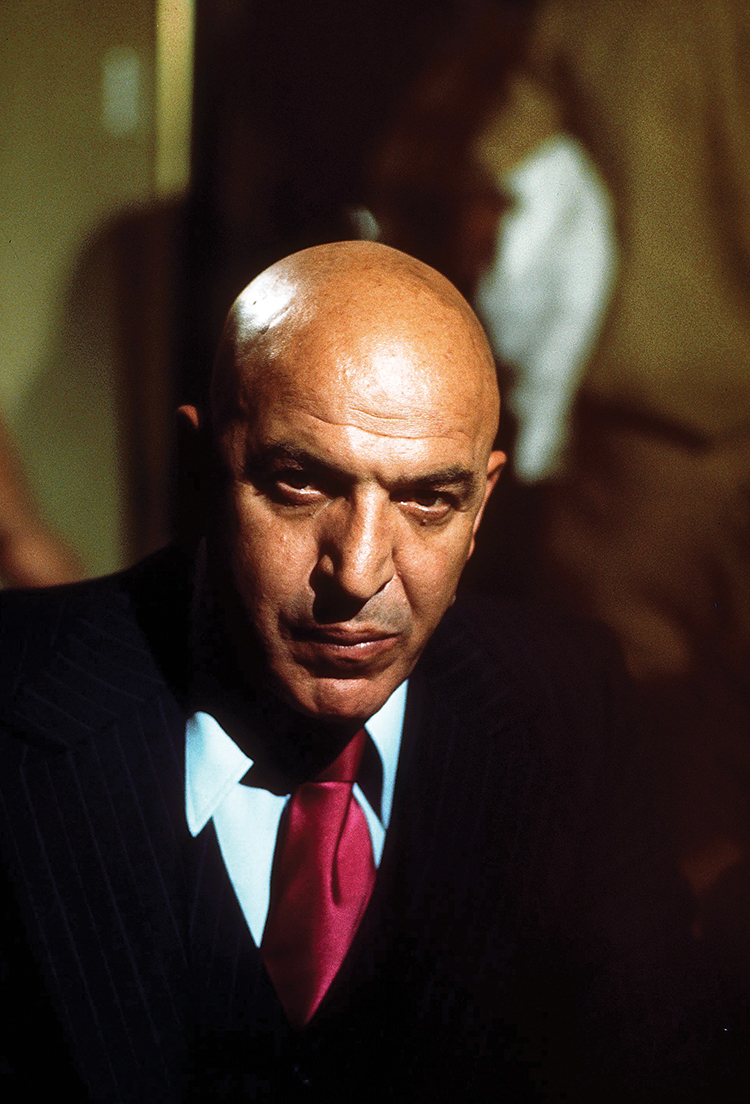

WHEN KOJAK FIRST HIT TELEVISION SCREENS in 1973, prime time was already flooded with police shows—Columbo, Adam-12 and Hawaii Five-0, to name a few. The new drama didn’t seem to have much to set it apart. Even Telly Savalas, who starred as Lt. Theo Kojak, never expected it to get past production.

By the end of the show’s first season, however, Savalas had won an Emmy, and Kojak was the most popular program on television. By the end of the second season, the lollipop-sucking, hard-nosed New York cop had reached icon status, and Savalas had one of the most recognized faces in the world. Before long, the show was on the air in 70 countries. It was so beloved in Japan that the actor dubbing Kojak’s dialogue shaved his head to resemble Savalas.

“[My father] was in awe that he lived a life where he could be … having lunch in the drugstore at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel with Warren Beatty and Omar Sharif,” says Savalas’ eldest daughter, Christina Kousakis, “and people would ignore them and ask for his autograph.”

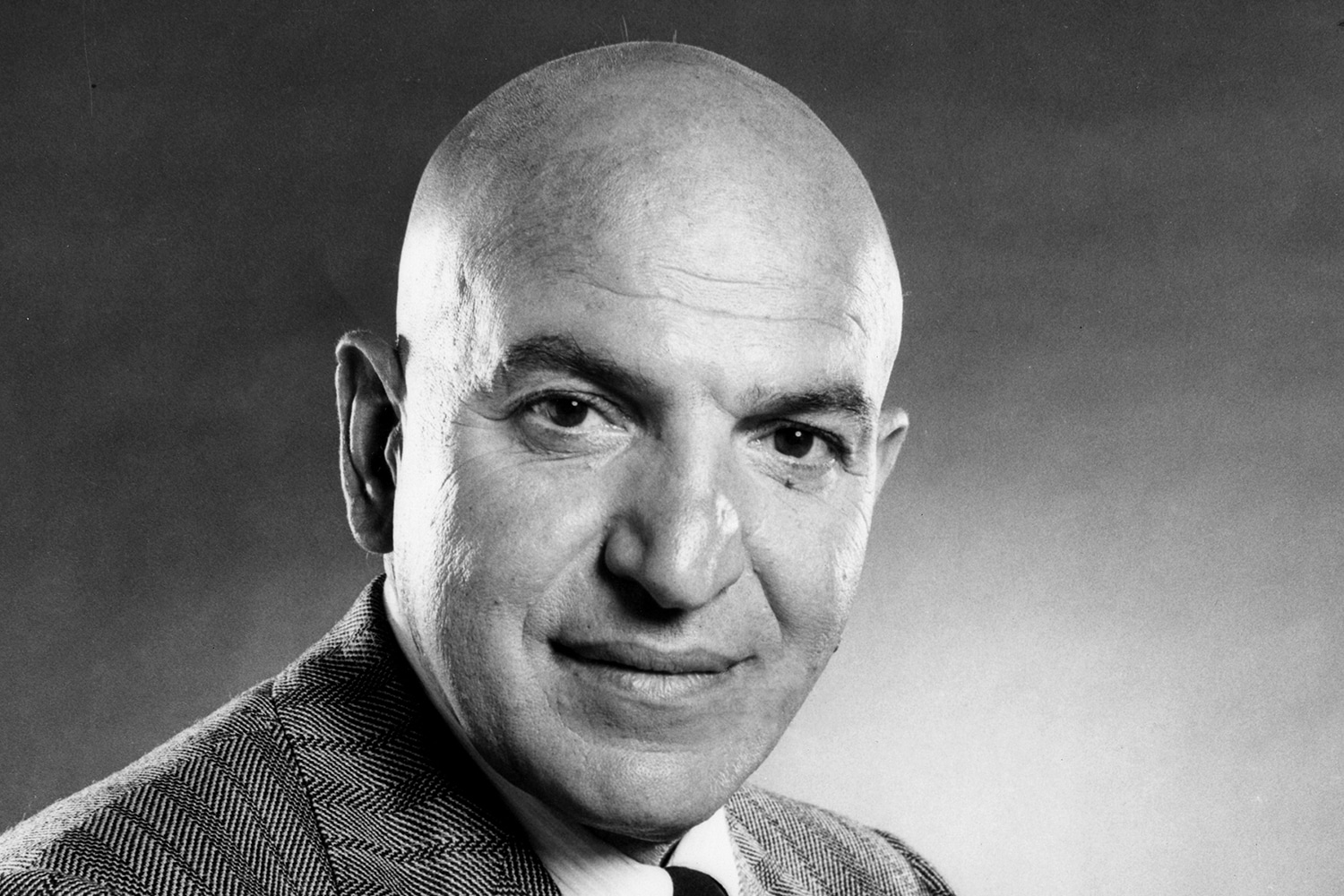

Savalas was an unlikely TV star. Until Kojak, he had been a well-paid and sought-after character actor, almost always playing unsympathetic roles: Pontius Pilate in The Greatest Story Ever Told; the sadistic, psychotic Archer Maggot in The Dirty Dozen; and Bond villain Blofeld in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Still, Savalas attracted fans among both men and women. “My father was very much a man’s man. He was into poker, sports and that sort of thing, so men were attracted to him,” says Kousakis. “But there was also something really appealing about him for women. He wasn’t Brad Pitt or Cary Grant good-looking. He was just an ordinary guy with a crooked nose, bald head, and not so thin, but he had this gentleness lurking just under the surface.”

A Humble Start

Born in 1922 to Greek immigrants in New York, Savalas learned to treat life as a roller-coaster ride. His father made a fortune in the import-export business, only to lose it in the Great Depression, forcing his family to move from a comfortable Long Island home to Manhattan’s gritty Lower East Side. The elder Savalas peddled baked goods from a cart with the help of Telly and his older brother.

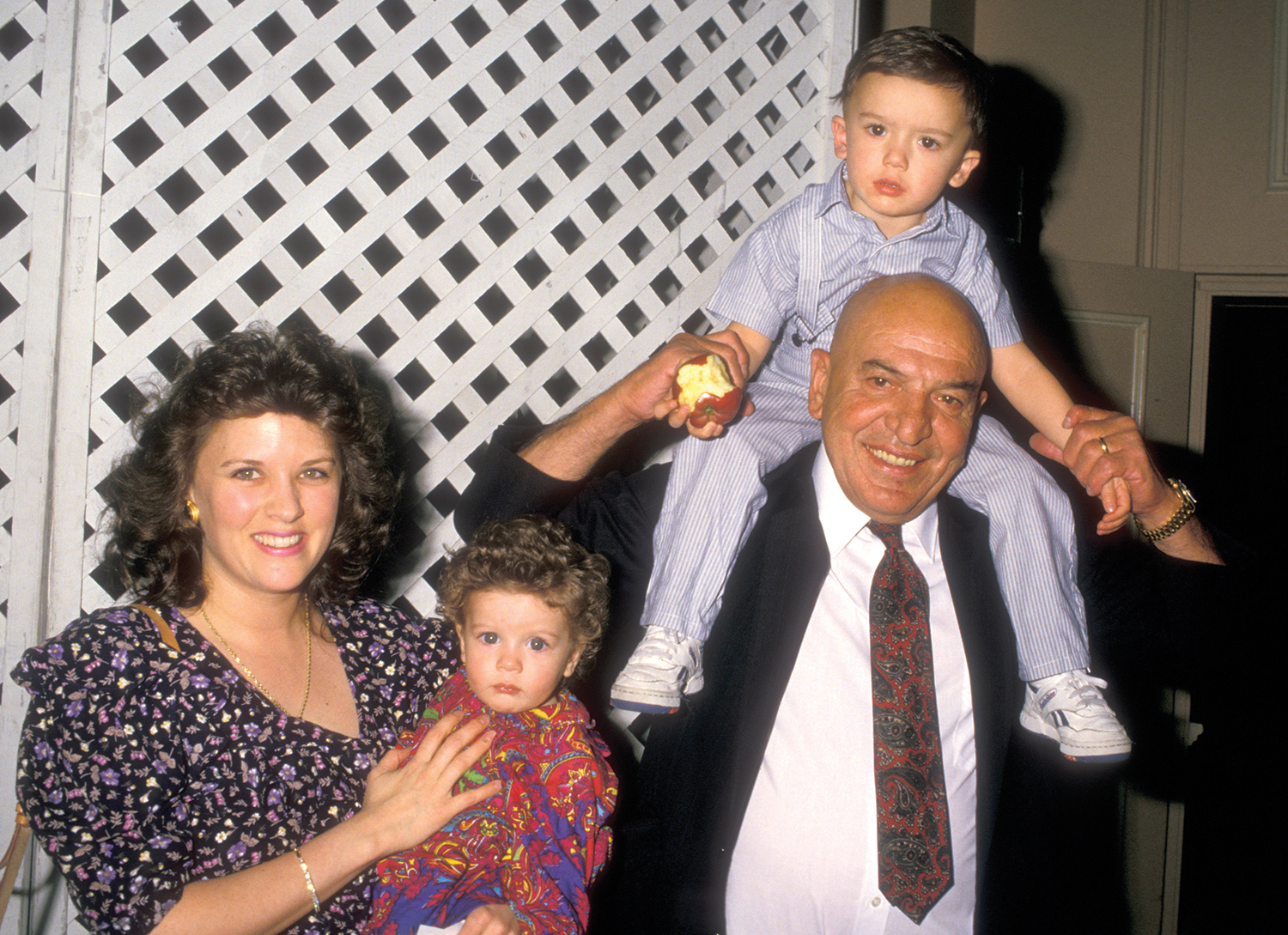

Telly Savalas and his wife Julie attend a 1988 charity event in Beverly Hills, Calif., with their children, Ariana (held by her mother) and Christian. Photo © mptvimages.com

As a young adult, Savalas never stayed with one job for very long. By 1957, he was 35 years old, divorced and living with his mother. He was also broke after investing in a failed theatrical venture. So when, two years later, an old friend asked him to find an actor who could play a convincing Greek judge for a television show, and Savalas couldn’t get anyone to show up, he auditioned himself and got the part. Within four years, he had an Academy Award nomination for best supporting actor in the 1962 movie Birdman of Alcatraz.

Savalas loved the fame his movie roles and Kojak brought, but he never felt part of Hollywood’s glitterati. “He would go to events, but he preferred to spend time with his family,” says Kousakis. Savalas stayed close to his siblings and even got his younger brother George a role on Kojak as the bumbling Detective Stavros. “He had six children with four different women, but everyone knew they had to get along, and it sounds improbable, but they did,” says Kousakis. Savalas’ youngest daughter, Ariana, concurs. “It’s hard for people to understand,” she says, “but there are no real divorces in Greek families. We all got together at Christmas.”

By the late 1970s, Savalas was living in Los Angeles in the Sheraton Universal Hotel, near the Kojak studio. Financially secure, he continued to work as an actor after Kojak went off the air in 1978, although none of his roles were as memorable. Part of the reason Kojak was so successful may have been that Savalas was a lot like the character. “Kojak is Telly Savalas and Telly Savalas is Kojak,” he told a People magazine reporter. In fact, Kojak’s “Who loves ya, baby?” catchphrase was the actor’s own—long before the television show had even started.

Get support and information about bladder cancer

Organizations and websites that offer support and information for people dealing with bladder cancer include:

A Dangerous Diagnosis

In 1989, Savalas was 67, married to his third wife, Julie, and raising their two young children, Ariana and Christian, in a large suite at the Sheraton Universal. “He always had something going on,” says Kousakis, whether he was acting in commercials, making travel films, competing in the World Series of Poker, investing in racehorses or putting out albums.

Savalas was a busy man who liked to present an invincible exterior to his family and the rest of the world, and when he started seeing blood in his urine, he chose to ignore it. “He wasn’t the sort of guy to have regular health checkups,” says Kousakis. Savalas’ father had died of bladder cancer, and his older brother, Gus, had recently been diagnosed and treated. “Gus kept telling him how important it was to catch it early,” says Kousakis, “and I think it may have caused him to think it was already too late to fix.” She finally resorted to trickery to get him to see a doctor. “I made an appointment with a doctor he knew and then told him that I needed him to give me a ride home to get him to show up,” she says.

Bladder cancer is the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States. According to the National Cancer Institute, there will be about 72,500 new bladder cancer diagnoses and more than 15,000 deaths from the disease in 2013. Savalas was, in many ways, a classic case: The cancer is more likely to be diagnosed in men than women and is significantly more common in whites than blacks, Asians or Hispanics. The median age at diagnosis is 73.

“Cigarette smoking is the No. 1 risk factor for bladder cancer,” says Jenny Kim, a urogenital oncologist at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. “There’s actually a linear relationship: The more you smoke, the higher the risk.” And while Kojak’s lollipop was a nod to the character’s attempt to quit smoking on the television series, Savalas himself was a heavy smoker for most of his life, as were his father and older brother.

“We think there may be a familial genetic component to most bladder cancers, but so far research hasn’t turned up any definitive evidence,” says Kim.

Most bladder cancers are diagnosed early when people visit their doctors with signs like blood in the urine, recurring urinary tract infections or pain during urination. The most important indicator for making a prognosis is whether the cancer has grown through the uroepithelium—the innermost lining of the bladder—into the underlying muscle layers of the bladder wall.

“The vast majority—about 75 to 80 percent—of patients first present when the cancer is still confined to the innermost lining of the bladder,” says Dean Bajorin, a genitourinary oncologist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. More than 90 percent of these patients will still be alive five years after treatment, which can include surgery with or without chemotherapy or immunotherapy.

Telly Savalas’ TV role as a tough new York City detective in Kojak made him a celebrity worldwide. Photo by Bud Gray / mptvimages.com

By the time Savalas was diagnosed, his cancer had spread to the underlying muscle layers of the bladder wall. “For these cancers,” says Bajorin, “about 50 percent of the patients will die of the disease despite treatment.” The treatment of choice then as now is a procedure called a radical cystectomy, in which a surgeon removes the bladder and nearby organs that may harbor cancer cells, such as the prostate. But Savalas emphatically rejected that option. “His own father had had the surgery and it had been really awful,” says Kousakis. “That was in 1947 or 1948 … and his father had been very incapacitated, he had a bag, it was gross and uncomfortable and like having no life.”

Today, surgical advances have made long-term side effects easier to manage. “Over the past decade or so, surgeons have perfected a technique in which they use a segment of the bowel to make a ‘new bladder’ inside the body, so that patients can urinate normally and not have a urine-collecting bag attached to the abdomen for the rest of their lives,” says Bajorin.

Another important advance: The use of chemotherapy before a radical cystectomy and the extensive removal of lymph nodes in the pelvis as part of the procedure have significantly improved the survival rate in recent years, Bajorin says.

Savalas opted to have as much of his cancer taken out as possible via cystoscope, followed by radiation. A cystoscope is a flexible instrument passed through the urethra directly into the bladder. Doctors can insert small instruments through the cystoscope to remove the tumor. For a few years, Savalas had cystoscopies every three or four months to check for new growths and seemed to be stable, but by December 1993, he started slowing down. “The cancer had metastasized to his bones and other organs, but he was really only very sick for about six weeks,” says Kousakis.

Living at the Sheraton Universal and surrounded by family and friends, Savalas experienced death nearly as dramatically as any role he had played. “We had a lot of trouble with the paparazzi,” says Kousakis.

“They’d heard that he wasn’t doing well and they were swarming around the hotel—they even put tape recorders in the coffee shop.” Then on Monday, Jan. 17, 1994, the Northridge earthquake decimated areas of Los Angeles, including a large part of the hotel. “His rooms … miraculously survived the quake,” says Kousakis. “He died five days later … and had all the privacy and dignity he wanted.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.