IN MARCH 17, 2004, Bob Denver, along with other surviving cast members of the 1960s television comedy Gilligan’s Island, gathered at the Hollywood Palladium, a concert hall on Los Angeles’s Sunset Boulevard. They were there to accept the second annual TV Land Award in the Pop Culture category, given for crossing the line from television series to pop culture phenomenon.

Photo © 2005 CBS Worldwide Inc. / Getty Images

The award was well-deserved. Forty years after the first episode aired in 1964, the show had achieved almost mythical status. Though original episodes of Gilligan’s Island aired for only three seasons, those 98 episodes have been in reruns for decades. Broadcast in more than 70 countries and dubbed into at least 10 languages, the show has been a staple of TV viewing for generations of children. In some markets, Gilligan’s Island was broadcast as many as five times a day, making it, by some estimates, one of the most widely syndicated shows ever. Scholarly treatises have been written about the program, and the Ginger or Mary Ann debate has been a topic of pub disputes for decades. The show has proved so enduring that, in 1992, 30,000 fans petitioned the governor of Hawaii to rename Maui “Gilligan’s Island.”

A Childlike Clown

The show’s popularity, especially among children, is in no small part due to Bob Denver’s portrayal of Gilligan, dubbed “Little Buddy” by the Skipper, a fellow castaway played by Alan Hale Jr. Gilligan was the well-meaning but bumbling first mate who managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory every time the castaways were close to escaping from the island. In her book, Gilligan’s Dreams: The Other Side of the Island, Denver’s wife Dreama, now 63, describes how the actor studied his then-3-year-old son Patrick to capture the wonder and curiosity of a child in the character of Gilligan. “He wanted kids the world over to identify with Gilligan, seeing that they could mess up and still have everything come out all right in the end,” she writes.

Bob and Dreama Denver stand in front of their home in Santa Barbara, Calif., in 1983. Dreama is pregnant with their son, Colin. Photo courtesy of Dreama Denver

By the time Gilligan’s Island first hit the airways in September 1964, Denver, 29, had already achieved fame on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, a TV sitcom that aired from 1959 to 1963, playing the beatnik, bongo-playing best friend Maynard G. Krebs. Like Gilligan, the Maynard character owes as much to Denver as to the show’s writers. “During the first year of playing Maynard, I was allowed to make up my own character,” Denver wrote in his autobiography, Gilligan, Maynard, and Me. “He was mine to create. Sounds a bit like Dr. Frankenstein, but it’s true.” Like Denver, Maynard was heavily into jazz and a bit of an iconoclast. The actor would take long breaks to go fishing in Maine or explore Tahiti and Bora Bora.

Born in New Rochelle, N.Y., in 1935, Denver finished high school in Los Angeles after his family moved there. He attended college locally at Loyola Marymount University, where he first got into acting doing college productions. After briefly flirting with the idea of attending law school, Denver decided to try professional acting. He supported himself with various jobs, including teaching elementary school and working at a post office, while he looked for roles. In 1958, the 23-year-old landed the role of Maynard G. Krebs after his sister Helen, who worked at 20th Century Fox, slipped his name in for a screen test.

Denver spent the next 11 years in Hollywood, including four years on the set of The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis and three on Gilligan’s Island. After a few years of working on two short-lived TV series, The Good Guys and Dusty’s Trail, Denver left television to go on the traveling dinner-theater circuit.

By 1972, Denver had married three times and fathered a son, Patrick, and two daughters, Megan and Emily. While performing in a dinner-theater production in 1977, he met Dreama, who would become his fourth wife. “By the time I met him, he had three ex-wives and three great kids and his career had seen a lot of ups and downs,” Dreama writes in her book. “He [felt] pigeon-holed. There’s no one else that looks like him, and people always saw him as Gilligan.”

But there were benefits to being so heavily typecast: Denver’s familiar face earned much-needed income.

“People assume that if they’ve seen you on TV for decades, you must be rich,” says Dreama. “But back in those days, actors didn’t know about residuals” (fees paid to actors and other creative staff when a program is rebroadcast). Denver’s weekly salary on Gilligan’s Island never exceeded $1,500, and the actors were paid off completely after all the episodes ran twice in the 1960s.

“We lived hand-to-mouth for a lot of our marriage,” says Dreama. Finances were especially rough after their son, Colin, who has severe autism and a seizure disorder, was born in 1984. Soon after, the couple moved to Bluefield, W. Va., about 10 miles from Princeton, where Dreama grew up. They devoted themselves full-time to caring for their son.

“When money was tight, Bob would go do personal appearances and that would give us enough to tide us over,” says Dreama. No matter how many years passed, people always wanted to see Gilligan.

Some patients are being helped by advances.

Had Denver been diagnosed with stage IV hypopharyngeal cancer now, he might have been a good candidate for treatment with Erbitux (cetuximab). Approved by the FDA in March 2006, Erbitux is the first targeted therapy for squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. The approval was based on a randomized trial of patients with stage III and IV pharyngeal cancers. Patients who received Erbitux along with radiation showed a median survival of 49 months, compared with 29.3 months for patients who received radiation alone.

But it doesn’t work for everyone. “It can stabilize about 50 percent of patients, but only 10 or 15 percent of patients show major tumor shrinkage and a durable response,” says David Pfister, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Because Erbitux works in a different way than traditional chemotherapy drugs—it locks on to a certain protein found on cancer cells and brings in immune cells to kill them—it has fewer side effects and can be used in patients like Denver who are too weak to handle standard chemotherapy.

For patients who are strong enough for chemotherapy, oncologists have been learning how to make traditional therapies more effective, for example, by using cisplatin or 5-fluorouracil before surgery in some patients to shrink their tumors so surgeons have a better chance of removing all the cancerous tissue and preserving laryngeal function.

Besides Erbitux, there haven’t been many significant advances since Denver was treated. “These rarer cancers aren’t high profile like breast or prostate cancers, and that makes it challenging both to conduct large‑scale prospective trials and to attract the attention of drug developers,” says Pfister. “If you’re developing a drug, you focus on common diseases.”

That doesn’t necessarily mean more advances won’t be forthcoming. “There is a spectrum of targeted drugs in the pipeline for different cancers … so some of these drugs might also be effective for throat cancers,” says Pfister, who points out that Erbitux was first approved to treat colorectal cancers.

A Rare, Aggressive Cancer

The March 2004 TV Land Awards would be Denver’s last public appearance. By November, both Denver and Dreama noticed that he was getting hoarse, but chalked it up to laryngitis. By March 2005, he had lost 20 pounds. Finally Denver realized it was time to find out what was wrong. He was referred by his family doctor to an ear, nose, and throat specialist who performed an endoscopy, threading a thin camera through his nose to look at his throat. After seeing an unusual growth around the voice box, the doctor sent Denver for an MRI to get a detailed view of the inside of his throat.

The scan results weren’t good news. Denver, 70, had stage IV hypopharyngeal cancer, a cancer in the lowermost part of the throat that connects to the esophagus and the windpipe. A large tumor had formed in Denver’s pyriform sinuses—small recesses on either side of the larynx—and had spread until it had invaded the cartilage of the larynx, the base of the tongue, the neck muscles, the thyroid gland and the submandibular lymph nodes along the base of the lower jaw.

“Hypopharyngeal cancers are one of the less common types of head and neck cancers, but when they do occur, the pyriform sinuses are the most common subsite,” says Kathryn Greven, the radiation oncologist at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C., who treated Denver. Roughly 52,000 people are diagnosed with head and neck cancers each year, representing about 3 percent of all cancer diagnoses in the United States. Of these head and neck cancers, in 2014, the American Cancer Society estimates there will be 14,410 new cases of pharyngeal cancer and 2,540 deaths from the cancer. Only about 2,500 new cases of pharyngeal cancer are diagnosed each year in the hypopharynx, where Denver’s cancer originated.

A biopsy of the tumor revealed that, like 90 percent of head and neck cancers, it was a squamous cell carcinoma, meaning it originated in the outermost layers of the cells that make up the throat’s lining. These cancers infrequently metastasize to distant sites like the liver, lungs or bone, but they do aggressively invade nearby tissues and lymph nodes. “With these cancers we look more at the stage, or where and how far the cancer has spread, than at the grade, which tells us how abnormal the cancer cells are, for prognosis,” says Greven. “Denver’s cancer had spread extensively … so that’s a very serious situation requiring aggressive treatment.”

In many ways, Denver was the classic patient. Pharyngeal cancers are two to three times more common in men than women, and most likely to be diagnosed after age 50. Denver, like 87 percent of patients with pyriform sinus tumors, presented late, when the tumor was already stage III or IV. “There is no good screening test,” says David Pfister, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. “Tumors in certain locations, like on the vocal cords themselves, will often present sooner because patients become symptomatic even with early stage disease. By contrast, pyriform sinus cancers will often be more advanced before patients develop symptoms such as voice changes or difficulty swallowing.”

According to the American Cancer Society, the five-year survival rates for stage III and IV hypopharyngeal cancers are 36 percent and 24 percent, respectively. For the relatively few patients whose cancers are diagnosed early, the outlook is somewhat better—the five-year survival for stage I cancers is 53 percent.

Three out of four head and neck cancer diagnoses can be attributed to tobacco and alcohol use. “Because of the anatomy, the pyriform sinuses really get bathed in alcohol and smoke,” says Pfister. Like many patients, Denver was a lifelong tobacco user, smoking more than a pack of cigarettes a day, according to Dreama.

As a result of heavy tobacco and alcohol use, “it’s common to find cardiovascular disease and other serious health problems that can complicate treatment” in people with a pharyngeal tumor, Pfister says.

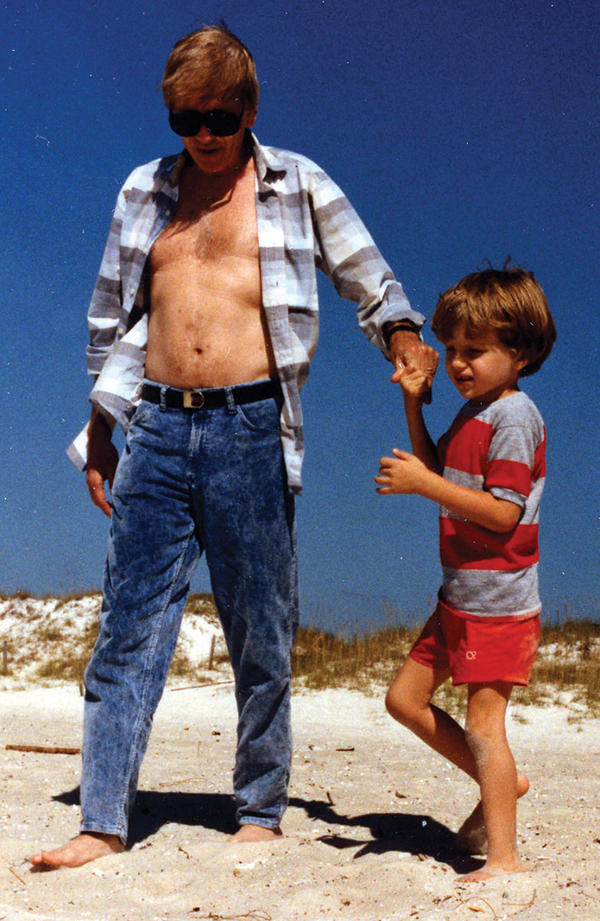

Bob Denver strolls along the beach in New Syrna, Fla., with his son, Colin, in the late 1980s. Photo courtesy of Dreama Denver

Denver was no exception. In fact, his heart problems were so serious that his doctors told him he would have to take heart medication before surgery, “if he was going to make it through the procedure,” says Dreama.

Denver did survive the surgery, but it wasn’t an unqualified success. “The surgeons had taken out so much tumor, there wasn’t much left to sew back together, but the pathology reports came back that Denver had positive margins, meaning there was still tumor left in his body,” says Greven. Because of his poor physical condition, Denver wasn’t a candidate for chemotherapy with cisplatin, which would have been the standard treatment along with radiation. And his radiation treatments had to be delayed while he built up enough strength to undergo a second surgery, a quadruple bypass to treat his cardiovascular disease.

By July 2005, four months after his original diagnosis, Denver had finally recovered enough from his surgeries to begin a six-week course of radiation. “It was a really terrible time,” says Dreama. “He could no longer talk, he had a stoma [a surgically created opening] in his neck so he could breathe, he could no longer walk, and he was getting worse and worse.” By the end of August, it was clear that Denver wasn’t going to get better. “We were hoping he would start to rebound [after] he was done with the radiation, but it wasn’t happening,” says Dreama. Instead he was battling pneumonia and unable to breathe without a respirator. By the last week of August, Denver had become totally non-responsive, not opening his eyes or moving a muscle. Several times his vital signs dropped low enough for nurses to rush Dreama into his room, thinking his death was imminent. On Sept. 2, 2005, Dreama let the doctors turn off the respirator, and he died the same day.

“The staff at the hospital had been huge Gilligan fans, and sharing the intimacy of the end of his life was almost spiritual for them,” says Dreama. “His legacy was the love of his fans. He always said that that made him richer than any residuals could have.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.