In 1951, a 30-year-old African-American woman named Henrietta Lacks underwent radiation treatment for cervical cancer at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. During her treatment, the surgeon who performed the procedure removed pieces of her cervix without her knowledge and sent them to a lab. Up until that point, researchers at Hopkins had been trying unsuccessfully to grow human cells for medical research using whatever tissues they could get their hands on. With Lacks’ cancer cells, they finally succeeded. And Lacks’ cells didn’t simply grow, they thrived beyond anyone’s imagination.

Author Rebecca Skloot explains that Henrietta Lacks’ family didn’t know for two decades that Lacks’ cells were being used in research. Photo by Manda Townsend

Lacks died eight months after her diagnosis, but her cells live on inside thousands of research labs around the world. Called HeLa cells, they have become one of the most important tools in medicine and have led to countless breakthroughs in the understanding and treatment of diseases. They have also spawned a multibillion dollar industry.

In The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, published in 2010, Rebecca Skloot recounted the story of the woman behind the famous cell line and the fact that her family did not know about Lacks’ immortal cells until more than 20 years after her death. This March, HeLa cells were again in the news after a team of researchers sequenced and published the cells’ genome without the permission of Lacks’ family. Cancer Today recently contacted Skloot to discuss her book, which is now being turned into an HBO film, and the issues it raises regarding the control and ownership of human tissues.

CT: How important have HeLa cells been to scientific research?

SKLOOT: Their significance really can’t be overstated. They were used to develop the polio vaccine. They went up in the first space missions to see what would happen to human cells in zero gravity. Henrietta’s cells were the first human cells ever cloned, some of the first genes ever mapped. They’ve been used to create some of our most important cancer medications, like vincristine and tamoxifen. They were essential for developing the HPV vaccine.

CT: How did HeLa research affect Lacks’ family?

SKLOOT: In the 1970s, scientists did research on Henrietta’s children without their informed consent to learn more about HeLa cells. So it’s not just a story about one woman. … It’s a story about multiple generations of one family used in research without consent.

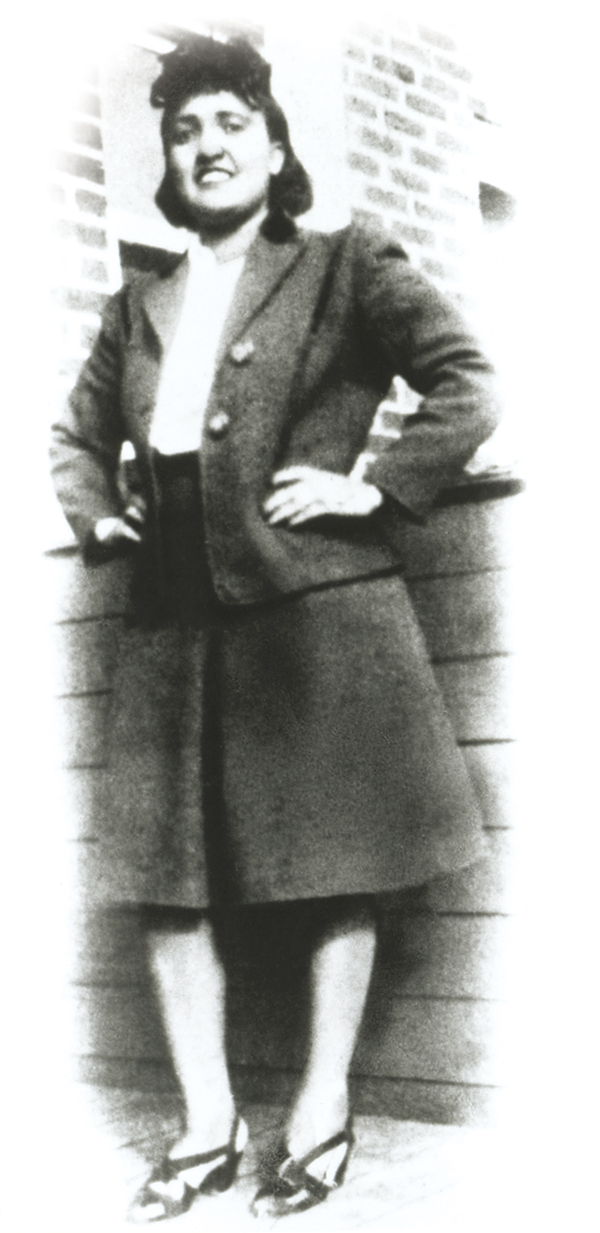

For more than 60 years, researchers have relied on cells removed from cervical cancer patient Henrietta Lacks to make some of the world’s most important medical discoveries. Photo courtesy of Obstetrics & Gynaecology / Science Source

CT: Was Lacks’ family ever paid for the use of her cells?

SKLOOT: No. In the 1950s, scientists knew very little about the basic functioning of cells—they couldn’t have imagined that someday those cells would be valuable. … George Gey, the scientist [at Hopkins] who first grew the cells, never sold HeLa cells, never tried to patent them or profit off them in any way. It wasn’t until many years later that the first for-profit venture began selling HeLa.

CT: Back then, it wasn’t illegal for doctors to take tissues from patients without their consent. Are things different today?

SKLOOT: Consent is still not required for much of tissue research. If a researcher takes tissues specifically for research and the “donor’s” name is attached, federal law requires informed consent. But if the tissue is taken for some other purpose—a routine biopsy or a fetal blood test—as long as the patient’s identity is removed from the sample, consent isn’t required.

CT: Is informed consent important?

SKLOOT: Most people understand that research on human tissues is essential for the future of medicine and scientific progress, and in general, people want to help with that. When doctors and scientists start doing things involving people’s tissues without telling them, it damages their trust, especially when money is involved. … Across the board what I hear is, “If they had just asked, we would have said yes.” But that’s often not what happens.

CT: HeLa cells continue to generate millions in profits, so why has the Lacks family never been compensated?

SKLOOT: Companies are concerned that giving money to the Lacks family would set a precedent: If they pay Henrietta’s family for use of HeLa cells, what about the millions of other people whose cells and tissues have been used in research? I created the Henrietta Lacks Foundation, which provides education and health care grants to Henrietta’s family and others who made significant contributions to research without consent. One of my hopes was that companies and research institutions might feel that donating to a foundation in Henrietta’s name would let them recognize her contribution to science and the impact it had on her family, without concern for setting a legal precedent. So far that hasn’t happened.

CT: What inspired you to write this book?

SKLOOT: [Lacks’ story] raises so many issues that are still unresolved today—issues related to race and class, access to health care, and bioethics. Should people have a right to control what’s done with their tissues once they’re removed from their bodies? And who, if anyone, should profit from those tissues? I hoped by raising those issues, and many others, I could help start a larger discussion about them.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.