IN MARCH 2011, Janet Freeman-Daily had a slight but persistent cough. She was about to take a family trip to China, so she asked her doctor for an antibiotic as a precaution. On the flight home from China, however, she and her husband, Gerry, began showing signs of a respiratory infection. His symptoms cleared up, but hers didn’t. Then she started coughing up blood. “We knew something was wrong,” Gerry says.

Freeman-Daily went back to her doctor, who once again prescribed an antibiotic. But her cough kept getting worse. On May 4, 2011, she had an X-ray, which revealed a 6-centimeter mass in her left lung.

Web-Exclusive Video

Learn more about Janet Freeman-Daily’s experiences and her thoughts on lung cancer and blame in this online video.

Freeman-Daily had a CT scan the same day and received the results by phone just as she arrived at home. “I was walking in my front door, and they told me it was suspicious for carcinoma,” says Freeman-Daily, who was then age 55. On May 6, she had a bronchoscopy, a procedure in which a tube with a small light and camera is inserted into the trachea. An analysis of the biopsied tumor specimen showed she had aggressive non-small cell lung cancer.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the U.S. and accounts for a quarter of all cancer fatalities, according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI). An estimated 234,030 people will be diagnosed with lung cancer in 2018, and an estimated 154,050 will die of the disease. Smoking causes most cases of lung cancer, but like Freeman-Daily, many people with the disease have never smoked. Overall, the prognosis for lung cancer patients is poor. The five-year survival rate for all types of lung cancer is only about 18 percent.

A Background in Science

Janet and Gerry live south of Seattle in Federal Way, Washington, not far from where Janet was born and raised in Tacoma. She was heavily influenced by her father, who was a medical doctor and engineer. “He very much encouraged my interest in math and science,” she says. That interest brought her to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, where she majored in mechanical engineering.

Janet Freeman-Daily and her husband, Gerry, enjoy a moment together on their deck. Photo by Rachel Coward

After graduating in 1978 and returning home to Washington, she joined the company that her grandfather had founded and that her father then ran, which designed and manufactured autopilot systems for fishing boats. A few years later, Freeman-Daily moved to Los Angeles to take a job with the Space and Communications Group at Hughes Aircraft, where she worked on communications and remote sensing satellites. Her employer paid for her to attend graduate school at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, where she received a master’s degree in aeronautics in 1984, as well as an engineering degree in aeronautics in 1986.

In 1989, Freeman-Daily’s cousin Frances, a single mother who lived in Connecticut, died of glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. Freeman-Daily, who was 33 and unmarried at the time, adopted Frances’ 3-year-old son, David, and returned to the Seattle area. “I really wanted to come home—I needed the support of my family,” she says. There, she joined Boeing’s Defense and Space Group, where she met her husband in 1991. In true Pacific Northwest spirit, she and Gerry were married on a snowbank on the slopes of Mount Rainier a year later.

Early Complications

Before starting treatment for her lung cancer, Freeman-Daily needed to take a month of antibiotics to clear up severe pneumonia—a common and sometimes fatal infection among lung cancer patients. In June 2011, Freeman-Daily was healthy enough to start treatment. She began 35 days of radiation treatment and also took doses of the chemotherapy drugs carboplatin and Taxol (paclitaxel) for about seven weeks. Initially, the results were mixed. A CT scan in late September revealed the tumor had shrunk by 90 percent, but it also showed the cancer had spread to lymph nodes inside her lung.

Her doctors had initially considered surgery to remove Freeman-Daily’s entire left lung, but a PET scan revealed that the cancer had spread to a lymph node in the middle of her chest, which made her cancer inoperable. She was diagnosed as stage IIIB, which includes cancers that have spread to lymph nodes in the center of the chest.

After undergoing intense radiation and chemotherapy, Freeman-Daily’s body needed a chance to mend before undergoing further cancer treatment. While she was recovering, though, things got worse. In October, a lump appeared on her neck near her collarbone and ballooned to 9 centimeters. “The cancer was getting out of my chest,” she says. “It was quite a shock.”

Clinical Trials Pay Off

To learn more about her disease, Freeman-Daily joined an online patient forum, which is how she learned about a clinical trial called the Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium Protocol, which offered tumor testing for abnormalities in 10 genes in lung cancer tissue. She hoped that her tumor would test positive for a genetic abnormality that could be treated with a targeted therapy.

Janet Freeman-Daily uses social media to help build online networks for patients. Photo by Rachel Coward

“Other patients told me about it, [but] my doctors in Seattle hadn’t heard of it,” she says. Freeman-Daily learned that the University of Colorado Cancer Center in Aurora was accepting patients for the trial, and they agreed to test her previously biopsied tumor tissue even though she was unable to travel to the center. Unfortunately, her test came back negative for all the abnormalities. Even so, the genetic testing heralded a turning point for her.

In January 2012, Freeman-Daily began chemotherapy again, undergoing six rounds of Alimta (pemetrexed) and Avastin (bevacizumab) over five months. Her side effects included nosebleeds, flu-like symptoms and peripheral nerve damage. But there was a big payoff: No evidence of cancer remained in her left lung or lymph nodes, and the new tumor near her collarbone had shrunk by 90 percent. She also underwent six weeks of radiation.

Then Freeman-Daily got more bad news. A PET scan in September 2012 showed that her collarbone area was clear, but her right lung, which had previously been unaffected, had two new hot spots that her doctors suspected were cancer. “We really didn’t know if I was going to make it,” she says.

After getting this disheartening news, Janet and Gerry visited her nephew in Denver. While there, she realized how close she was to the University of Colorado Cancer Center, so she contacted the genetic testing trial coordinator to arrange a time to stop in to personally thank the team. There, she met Paul Bunn, the oncologist who had agreed to test her tumor samples. This is where luck enters Freeman-Daily’s story.

Janet Freeman-Daily Photo by Rachel Coward

Bunn told her that other tests were now available for more genetic abnormalities, and that he still had some of her tumor sample left. This time, Freeman-Daily’s cancer tested positive for a mutated form of the ROS1 gene, an abnormality thought to be present in just 1 to 2 percent of lung cancer cases.

In November 2012, Freeman-Daily enrolled in an early-phase ROS1 clinical trial for Xalkori (crizotinib), a drug that had been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 to treat patients with late-stage lung cancer who have an abnormality in the ALK gene. Eight weeks after she started Xalkori, the hot spots in Freeman-Daily’s right lung were gone, and she has had no evidence of cancer since.

The FDA approved Xalkori for treating ROS1-positive lung cancer in 2016. But Freeman-Daily continues to take the drug as part of the ongoing clinical trial to help researchers learn more. Every six weeks, she flies to Denver to pick up medications and get scans. While there, she usually stays with her nephew, his wife and their two young children. “Being with family really helps,” she says.

All along, she’s worked closely with her medical team. “As one of the earliest cases of patients living for years with advanced lung cancer, Janet shows the importance of involving patients in decisions,” says Steve Kirtland, her pulmonologist at Virginia Mason Hospital in Seattle. In fact, he finds that with her science background, she is just as likely as he is to bring up the latest research findings. “I am blessed to know her and to have a patient who is a true rocket scientist,” Kirtland says, alluding to her career in the aerospace industry.

Building Patient Communities

Now, Freeman-Daily’s focus is on helping other people with lung cancer. “My side effects are mild so I have a lot of energy. I feel I can make a real difference,” she says, noting that she is able to manage side effects of edema and pulmonary embolism with medications.

In 2013, Freeman-Daily teamed up with Deana Hendrickson, a patient advocate who lost her mother to the disease. The two met via an online patient network for lung cancer patients, and together they created a Twitter community called Lung Cancer Social Media Chat (#lcsmchat), which brings together patients, caregivers, physicians and researchers. The chats take place every two weeks and explore topics such as “when doctors disagree,” “advocacy and burnout” and “lung cancer research: why we need it and how we can get more.”

“Recruiting Janet is the best thing I ever did,” says Hendrickson. “She’s the heart and soul of LCSM Chat.”

In 2015, with the help of fellow lung cancer survivors Lisa Goldman, Tori Tomalia, Lysa Buonnano and the late Stuart Grief, Freeman-Daily co-founded another online community—a Facebook group called the ROS1ders. Pronounced “ROS wonders,” the group is open to people whose tumors have this abnormality. Now, the ROS1ders have a website and are harnessing their strength in numbers to drive cancer research.

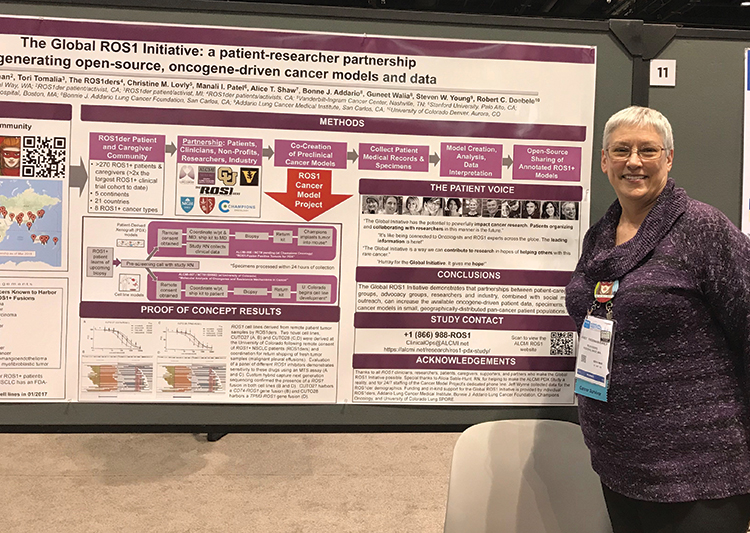

Janet Freeman-Daily stands before a poster she presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2018 in Chicago. The poster explains the Global ROS1 Initiative, an effort to drive research that benefits patients with the ROS1 mutation. Photo courtesy of Upal Basu Roy, Lungevity Foundation

“Pharmaceutical companies and academia are not moving fast enough,” says Bonnie Addario, a long-term lung cancer survivor who founded the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation and the Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute. “The ROS1ders are pulling together, saying ‘We can do this better.’”

The group made a list of research goals, and the Addario Lung Cancer Medical Institute is coordinating with ROS1 researchers and the pharmaceutical industry to advance those goals. Called the Global ROS1 Initiative, the effort is led by Christine Lovly, a medical oncologist at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee. Developing new models of ROS1 cancer is high on the list.

Models, such as cancer cell lines grown in the laboratory, are critical because they help researchers test potential treatments. And the more models, the better. “Just as not every person is the same, not every cell line reflects all ROS1 cancers,” Lovly explains. “For example, not all ROS1 cancers respond to Xalkori.” ROS1 models are scarce, however, partly because the genetic abnormality is so rare.

This is where what Freeman-Daily calls the “patient power” of the ROS1ders comes in. Patients in the group volunteer to provide samples of their tumors to researchers, helping them establish more ROS1 models to test new approaches. The models will be available to all researchers, and all resulting data will be open access. “This is a very different approach that all started with patients—it’s groundbreaking,” Lovly says. “We can achieve more if we work together.”

Even before joining the Global ROS1 Initiative, Lovly knew Freeman-Daily because they both participate in the NCI’s monthly lung cancer conference calls. “Janet is very involved in the lung cancer research community and is probably the strongest voice in making sure that research goals are aligned with patient goals,” Lovly says.

Freeman-Daily says she’s just doing what comes naturally. “How many people get to spend their lives doing something they love and that makes a difference in other people’s lives?” she asks. “I’ve found my purpose.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.