ONE HOT DAY last July, Kanakba Viraji Pingal invited me to her home in the remote Indian village of Vadala, a community of some 1,000 to 2,000 people, to talk about her brush with cancer several months earlier. I had just met Pingal in the town of Mundra at the office of Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan, a nonprofit organization that helps women make informed choices about their lives and address gender inequality in their villages. After leaving Mundra, we drove 20 minutes to reach her village, which, like Mundra, is in the district of Kutch within Gujarat state, on India’s west coast.

Pingal, 38, may not be the typical rural Gujarati woman: In addition to volunteering with the nonprofit, she also holds a unique position in her village as a community health worker for India’s National Rural Health Mission. But in many other ways, her life in Vadala looked much like that of many other traditional rural women I met in Gujarat. She lives in a tidy three-room house with her husband, a day laborer she married when she was 13; two of her four children; and her mother-in-law. Through the assistance of a translator, Pingal shyly discussed the events that led to her getting medical treatment despite Vadala’s lack of health care services—a widespread problem in rural India—when she was experiencing unusual symptoms oftentimes characteristic of uterine cancer.

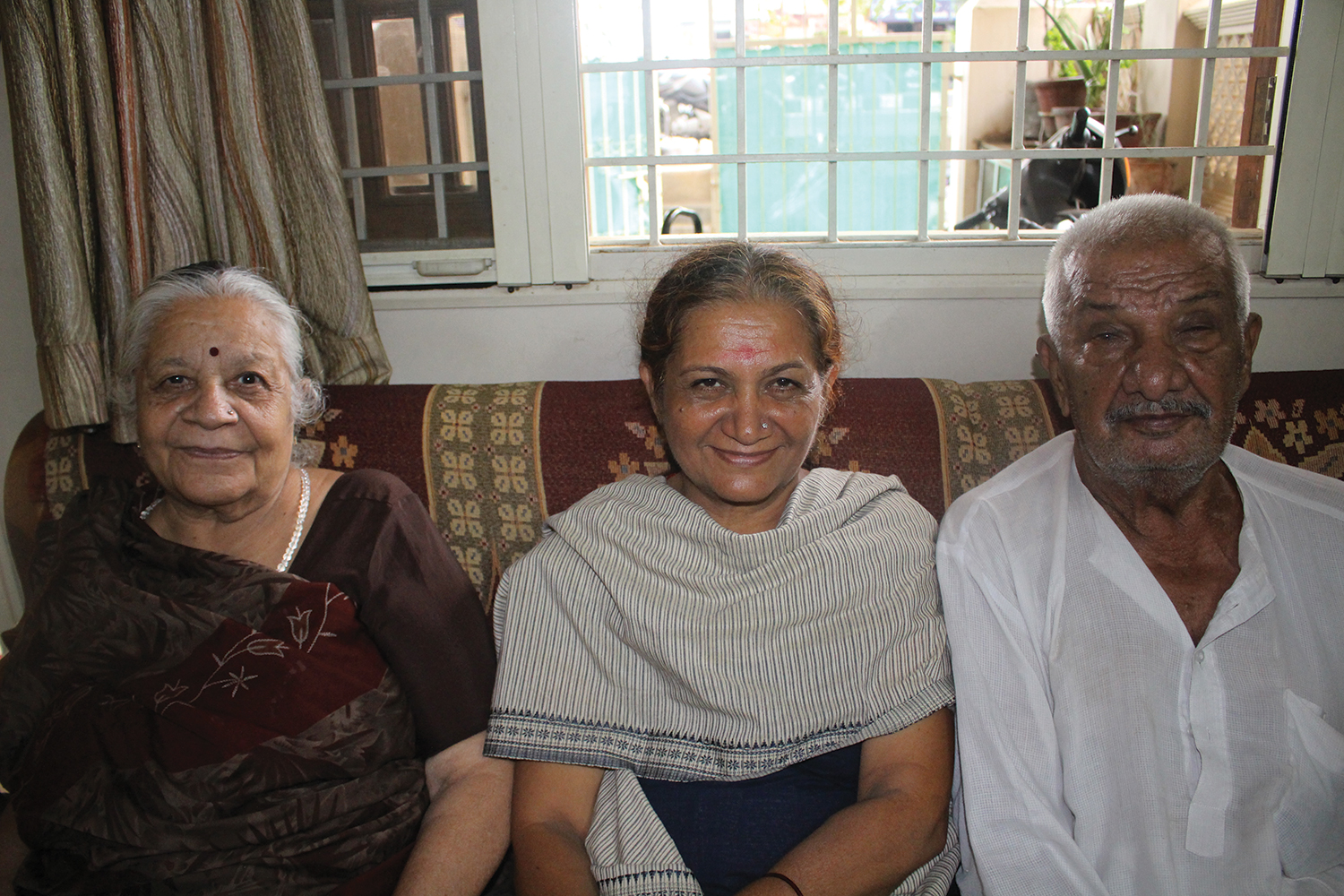

Breast cancer survivor Raxa Tanna (center) sits with her parents at her sister-in-law’s home in the city of Bhuj. Photo by Cynthia Ryan

A few days later, two hours by car and yet a world away, I met Raxa Tanna, 53, at the modern home of Tanna’s sister-in-law in Bhuj, a city of nearly 150,000 in Gujarat. We were not far from Tanna’s own similarly middle-class home. Before she married at 23, Tanna told me, she had attended school until the Indian equivalent of ninth or tenth grade and then helped her parents manage their household. A mother of two adult sons, Tanna clearly and confidently recalled her experience of being diagnosed with breast cancer in 1999 after finding a lump, the treatment she was prescribed, and the way she educated herself about the disease.

The stories of these two women—one rural, one urban—stood out among many I heard during my visit to Gujarat, where I traveled last summer to get a closer look at rural cancer care in modern-day India, a country of 1.24 billion that is poised to become the globe’s most populous nation by 2030. In recent years, many parts of India have progressed technologically and economically, even while the lives of many Indians have remained essentially unchanged. That was clear to me as I traveled through Gujarat, where, especially in rural regions, I encountered women whose lives did not appear to differ much from their great-grandmothers’ in terms of their traditional family roles and customs—or their medical care and knowledge of cancer’s signs.

“In spite of so much media and awareness about cancer symptoms provided by various organizations throughout Gujarat, we are still not reaching many in the rural areas of India,” says anesthesiologist Geeta Joshi, the deputy director of Hospital and Support Services and Education at the government-funded Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute in Ahmedabad, the largest metropolitan area in the state, with more than 5 million people. Shaking her head at the unfortunate reality, she gives an example: A rural woman working as a domestic servant arrived at her office following a positive breast biopsy with a tumor that was “popping out of her breast.” When Joshi asked the woman why she had waited so long to see a doctor, Joshi recalls, the woman said she “didn’t think it was anything important.”

Doctors say there remain far too many patients like this one, who seek medical help at an advanced stage of disease. But during my visit, I also learned about emerging efforts in cancer care that are aiming to improve the plight of women in small villages like Pingal’s. As a result of these nonprofit and government initiatives, some rural women are, often for the first time, receiving information about cancer symptoms along with access to cancer screening and treatment.

A path in Vadala leads to Pingal’s home. Photo by Cynthia Ryan

A Cancer Diagnosis in Urban Gujarat

Even though both Pingal and Tanna live in Gujarat, in many ways, I observed, they occupy two different worlds: Tanna’s being not just urban, but more modern as well.

Hospitals in most big cities in India offer cancer screening services like mammography, and include facilities to provide radiation and chemotherapy treatments, says Joshi. Gujarat, she adds, has many centers like this—with a mix of private, trust-run and government-run institutions.

Tanna has a regular doctor who has kept her informed over the years about cancer symptoms and screenings. So when she discovered a lump in her right breast in 1999, she was aware it could be a sign of breast cancer. “I knew there was something there so I went right away to my doctor in Bhuj for a biopsy,” she told me matter-of-factly, as we spoke in her sister-in-law’s home.

Rural health camps offer women in outlying areas access to cancer information and screening.

For more than a dozen years, government and nonprofit organizations in India’s Gujarat state have been providing many rural women with cancer information and screening at “health camps,” which may be held in their villages or at a regional health care facility. Local village leaders often help publicize the scheduled camps and encourage people to attend.

Cancer education camps may last one or two days and can serve as many as a couple hundred rural people in one or more villages. Doctors, nurses and other trained health care professionals introduce the women to the importance of cancer screenings—including screening for cervical cancer using a technique commonly employed in developing nations, called visual inspection with acetic acid—and how best to identify potential signs of cancer. In addition to the informational camps, separate health camps actually offer these screenings, biopsies if needed, and physician consultations. Some camps screen for other cancers, such as head and neck, oral, breast or prostate cancers.

In 2011 and 2012, the government-funded Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute served nearly 8,000 patients who were identified and cared for through its free cancer detection camps and a mobile screening van that visits rural villages. When patients from the camps need follow-up care, they can go to the Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute facility in Ahmedabad, the largest cancer hospital in western India. Patients referred there from the health camps can get help paying for transportation and their follow-up care.

The nonprofit Shri Bhojay Sarvodaya Trust in Mandvi examined nearly 4,000 women from rural areas during its screening camps in 2013, says trustee Liladhar Manek Gada. Women needing further medical attention are identified, he says, and encouraged to travel to the Bhojay trust’s hospital in Mandvi or to Mumbai for surgery, chemotherapy or radiation treatment, with assistance to pay for travel, food and lodging. Some will go, while others won’t.

With the help of a specialist in Rajkot, a much larger city 150 miles from Bhuj, with a population of nearly 1 million, her doctor had the biopsy analyzed. “He told me it was positive for cancer, and I needed to get an operation,” she said. She shared the report with her family, who “pushed me forward to have the operation.”

Tanna’s mastectomy was performed at a modern private hospital in Mumbai, more than 500 miles from Bhuj, within two weeks of her biopsy. After the mastectomy, Tanna told me, her doctor assured her that her lymph nodes showed no sign of cancer and that the disease had been detected at an early stage. She was instructed to begin hormone therapy, which she took for three years, and no other treatment was recommended, she said.

One part of Tanna’s story that stood out to me was her confident approach to trying to remain healthy. She told me, “My lymph nodes had no cancer and I felt good” following the surgery and hormone therapy. She continues to travel to Mumbai for checkups, is “aware and alert” to signs of recurrence, and has added yoga and traditional herbal remedies to her daily routine.

The support of Tanna’s family and their willingness to talk about her disease also struck me. Tanna’s husband and children, her parents, her siblings and their families all accompanied her to Bombay Hospital in Mumbai, and they all stayed in the city with her for the entire week she was hospitalized. On the day I spoke with Tanna, many family members were present—her parents, sisters-in-law, brothers-in-law, siblings, nieces and nephews. They were all knowledgeable about the details of her diagnosis and treatment and spoke frankly about her cancer. It was a stark contrast to my interactions with many of the rural women I encountered, whose traditional culture seemed to discourage discussion of personal health matters between generations and genders.

Cancer statistics probably underestimate cancer incidence in Gujarat.

Statistics reflecting cancer incidence and mortality in the Indian state of Gujarat are difficult to gather. The state is home to 62.7 million people, more than half of whom live in thousands of rural villages dispersed over a wide region. Data for Gujarat’s urban centers is also lacking. In 2010, the Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute reported nearly 26,000 newly diagnosed cancer patients being treated at its facility, located in Ahmedabad, the largest metropolitan area in the state.

But that figure likely underestimates the area’s cancer diagnoses, according to anesthesiologist Geeta Joshi, the deputy director of Hospital and Support Services and Education at the institute, who notes that health care providers in the state are not required to report cancer cases to a registry.

The Rural Experience

For a woman in a rural setting, the medical and support system is frequently very different.

The geographic distribution of the scattered village and tribal populations of Gujarat’s Kutch district makes it difficult to provide residents with medical care, says Liladhar Manek Gada, a trustee of Shri Bhojay Sarvodaya Trust, a nonprofit organization that operates a hospital with a surgical facility in Mandvi, a busy port city in Kutch, as well as cancer screening clinics that serve women in remote regions. “Seventy percent of the population of Kutch lives in villages, and the district [of Kutch] covers more than 45,000 square kilometers [more than 17,000 square miles],” he explains. “We don’t know where they are all located, and many people living in rural areas do not necessarily seek the assistance of a trained physician.”

Getting to health services is challenging for villagers, he says. Even though most have access to some form of transportation, whether a neighbor’s motorcycle or a camel-pulled cart—or a complimentary van provided by the Bhojay trust for patients who don’t have other options—travel for health care is time-consuming and disruptive to the daily functioning of the family.

Beds line a hall at the Shri Bhojay Sarvodaya Trust facility in Mandvi in preparation for the day’s surgeries. Photo by Cynthia Ryan

In rural areas of Gujarat, I witnessed firsthand how the difficult nature of women’s lives can hinder their ability to take the time to seek preventive medical care or treatment, whether for cancer or other health issues. Women here tend to be the cornerstones of the family unit and, as they and Gada explained to me, often place their own well-being second to attending to the needs of their children, husbands and extended family members. The rural women I met in Gujarat were also responsible for much of the labor outside the home: tending to goats, cattle and chickens, planting rice by hand, and making long walks to retrieve water.

For health issues, many rural residents, both men and women, rely on midwives and elders from their villages, often following “advice that has changed little” over generations, Gada says, despite medical advances taking place elsewhere in the country.

Recognizing that women in rural regions of Gujarat often have little power over their lives and may be unable to leave home to get care, cancer care institutions like the Bhojay trust and the Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute have been offering “camps”—or clinics—that provide rural Gujarati women with information about cancer, as well as screening services, in many cases right on their own turf.

Several Indian organizations are working to bring cancer care and other medical services to residents in rural India. Among them are:

It was at one of the Bhojay trust’s health camps three years after the onset of her symptoms that Pingal got the answers and care she needed. She showed up at a local health camp armed with details about her symptoms—heavy menstrual bleeding, severe cramps, excessive gas and stomach acidity, and abnormal vaginal discharge—and ready to discuss her experience with one of the visiting physicians.

Pingal, I learned, already had some unusual experience in speaking up about health care—a result of her three years of work with India’s National Rural Health Mission, for which she has been trained to counsel people in her village about issues related to children, nutrition, sanitation, hygiene and immunizations—and so she had already sought answers about her symptoms previously from two doctors, but with no success. At the health camp, however, she was referred that same day for a biopsy and just three days later underwent surgery, including removal of a growth and her uterus, at the Bhojay trust’s facility in Mandvi, 40 miles from her village.

Financial assistance was provided to Pingal through the trust, and she stayed at the public facility free of charge until she could return home. Fortunately, she said, the doctors told her the growth was precancerous.

Initiatives are underway in the U.S. to address cancer in rural areas. This is web-exclusive content.

In the U.S., efforts are also underway to provide rural populations with improved cancer care. Learn more at these sites about initiatives designed to improve the health of rural Americans:

National Cancer Institute’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities

Appalachia Community Cancer Network

University of Kentucky Rural Cancer Prevention Center

Pingal told me she is relieved that she had the chance and the know-how to present her symptoms to doctors at the health camp and to request further evaluation at the Bhojay trust. “They listened to me,” she said. “They knew I was telling the truth about my symptoms.”

Identifying and reaching rural patients like Pingal is a huge feat, but so is persuading family members and village leaders that caring for female cancer survivors will benefit the wider community, I observed. Successful health education efforts must aim to change lifestyles, suggests Gada of the Bhojay trust. He says: “We tell the families of patients, ‘Your wife, your daughter-in-law is important to your family. She needs to be well to be a mother and to care for you.’ ”

Patients wait with attendants in a pre-operative room at the Bhojay trust. Photo by Cynthia Ryan

Counseling Their Communities

Pingal and Tanna have both emerged from their experiences recognizing the need to share what they have learned with members of their communities.

An 11-minute video narrated in English describes the activities of Shri Bhojay Sarvodaya Trust in the Kutch district of Gujarat.

Tanna said that she is much more outspoken with other women about the importance of knowing their bodies and seeing a doctor for regular checkups. “Talking,” Tanna told me, “means power.”

And Pingal, whose life reflects another side of India, one in which women have not traditionally held positions of authority, said that she sees herself as a “role model in my village,” explaining that she now has the ability to influence health care decisions made by others in her close-knit community.

“I work more actively with my organization [the National Rural Health Mission] now and take more pride in my [health outreach] work,” she told me. “I know my story can make a difference.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.