SHARI LEWIS was only 18 years old when she made a name for herself in 1952 as a winning contestant on the popular television show Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts, a 1950s precursor to American Idol. After that early success, the young puppeteer and ventriloquist worked in local children’s television in New York City, until, in 1956, she appeared on Captain Kangaroo, a nationally syndicated children’s television series. But the show’s producers didn’t like the large puppets the diminutive entertainer used in her act.

Shari Lewis strikes a pose with Lamb Chop in the mid-1990s. Photo by Gregory Pace / Corbis

“Before they booked me, they came to me and said, ‘Your dummies are so big and clunky, you’re 5 feet tall, don’t you have anything that’s dainty?’ ” Lewis recalled in a 1997 newspaper interview. She did have one thing: a homemade sock puppet depicting a sheep with absurdly long eyelashes that a friend had created after her father joked, “If Mary had a little lamb, why shouldn’t Shari have one, too?”

To see if it would be a good match, Lewis spent an hour before the mirror improvising routines with the puppet, which she named Lamb Chop. “It was quite clear. [Lamb Chop] just came to life like no puppet I had ever worked with before,” she said. Lamb Chop was an instant hit on Captain Kangaroo, and that break led to another local TV show in New York City, Shariland, for which she netted two Emmy Awards in 1957.

Lamb Chop, Lewis’ perpetually inquisitive and frequently smart-aleck sidekick, was so popular that NBC gave Lewis her own network show from 1960 to 1963. The Shari Lewis Show was essentially a one-woman program featuring the puppets Lamb Chop, Charlie Horse and Hush Puppy. Its playfulness and gentle humor appealed both to parents and children, making Lewis and Lamb Chop trusted icons for the preschool set.

A Natural Performer

Lewis attributed most of her success to her parents. Born Shari Hurwitz on Jan. 17, 1934, to a father who was an amateur magician and a mother who was an accomplished pianist, she grew up in the Bronx section of New York City during the Great Depression. Lewis’ parents encouraged her natural desire to perform, paying for lessons in everything from ballet to ventriloquism. “My first memory of my momma is her never putting me down,” Lewis once said. “I really had a sense of being cherished, and that is the greatest gift she gave me.”

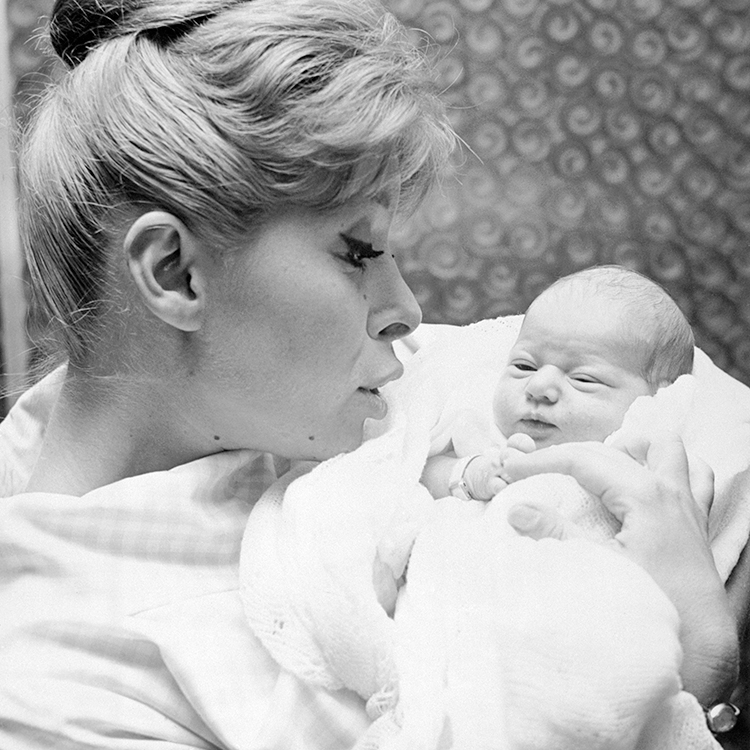

According to Lewis’ daughter, Mallory, her only child from a 46-year marriage to publisher Jeremy Tarcher, “My mother really valued childhood, and that came through in everything she did. But she also had this very focused, very driven need to succeed—she was one tough lady.”

Lewis’ toughness was tested time and again in her adult life. After cartoons became popular on Saturday morning television, her show was canceled in 1963. Lewis was devastated. “All of it … my entire field crashed around my ears,” she said. But she kept performing, doing her act for adult audiences in Las Vegas casinos and opening for stars like comedian Jack Benny. She also moved to England to do 18 shows a year for the BBC. “In order to do my children’s work, I had to leave the country … it was very saddening,” she said. “The only bout with depression that I’ve ever had was at that period.”

Lewis persevered with her puppets. By 1975, she was again doing children’s programming in the United States with The Shari Show, which included her typical mix of Lamb Chop, learning and fun. But in 1984, Lewis faced a breast cancer diagnosis. She immediately took control of the situation, closely questioning her doctors and determining her treatment plan. While some of her doctors recommended a mastectomy, Lewis did her own research and opted instead for a lumpectomy, radiation and taking tamoxifen, a drug that blocks the cancer-promoting effects of estrogen on breast tissue.

“She decided what was good for Shari, she put together her own [regimen] and followed it carefully,” said her husband in a television interview.

Lewis maintained a regular presence on children’s television, most notably on PBS with the hit Lamb Chop’s Play-Along, which aired from 1992 to 1997 and endeared her to a new generation of children. It was the first children’s show in seven years to best Sesame Street for a writing Emmy.

In 1998, Lewis was at work taping episodes for a Lamb Chop’s Play-Along spinoff called The Charlie Horse Music Pizza when she experienced abdominal pains and stopped eating. Her daughter, who co-wrote and co-produced the show, insisted she see a doctor.

“She wasn’t the sort of person to complain or stop the show for anything,” Mallory says. A day later, her mother was diagnosed with uterine cancer and told she had six weeks to live. But Lewis carried on. “I’m coming back to the studio, and I don’t want to see any red eyes,” Mallory recalls her mother telling her.

Obesity is associated with an increased incidence of endometrial cancer.

While National Cancer Institute data suggest that the overall incidence of endometrial cancer has been relatively stable for the past decade, many clinicians report seeing the condition in younger patients at a growing rate.

It seems the trend is tied tightly to the obesity crisis. “Fat isn’t biologically inert,” says gynecologic oncologist Nita Lee of the University of Chicago Medical Center. “It plays a large role in the metabolism of estrogen, high levels of which we have known for a long time promote endometrial cancers.”

Lee notes that epidemiological studies show an association between high obesity rates and an increased incidence of endometrial cancer. And even though most cases of endometrial cancer are found early and cured, many patients already have or go on to develop other conditions associated with obesity.

“What’s happening is we’re getting these women through cancer treatment successfully, and then we’re losing them to a cardiovascular event or other obesity-related morbidity five or 10 years later,” says Lee. “It’s something that is important for women to know, because it is something that they have control over.”

A Common Cancer

Tamoxifen, which Lewis took after her breast cancer surgery and radiation, increases the risk of uterine cancer. The most common type of uterine cancer is endometrial cancer, which affects the lining of the uterus. Endometrial cancer makes up more than 80 percent of uterine cancer cases and is the most common gynecological malignancy in the United States, accounting for about 6 percent of all cancers in women and 3 percent of all new cancer cases. In 2015, an estimated 54,870 new cases will be diagnosed and approximately 10,170 women will die from the disease in the U.S.

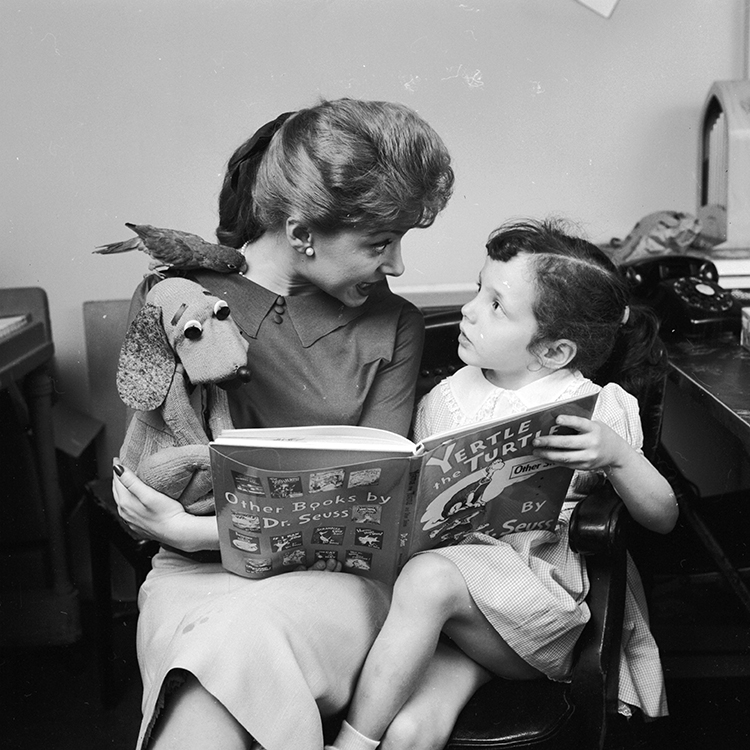

Shari Lewis reads the tale of Yertle the Turtle to a young girl. Photo by Jacobsen / Three Lions / Getty Images

In most cases, however, endometrial cancer is treatable, says Nita Lee, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Chicago Medical Center. About 70 percent of women diagnosed with endometrial cancer are categorized as stage I or II, meaning the cancer has not spread beyond the uterus. Women with early-stage endometrial cancer normally undergo a hysterectomy without further treatment and have an excellent prognosis.

Given Lewis’ poor prognosis, she likely had a late-stage endometrial cancer or a rare, highly aggressive uterine cancer, says Ginger Gardner, a gynecologic oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. The five-year-survival rate for endometrial cancer falls if the cancer is detected after it has spread to regional lymph nodes, and it is less than 20 percent when the cancer spreads to organs such as the liver, lungs or bone.

Lewis first underwent a hysterectomy and then was offered chemotherapy, which her daughter encouraged her to undergo. Despite her poor prognosis, Lewis agreed.

“When she had breast cancer, she was all fired up, but this time she made a mental shift,” says Mallory of her mother’s uterine cancer diagnosis. “I think she realized that there was no coming back from this at the top of her game, so she just sort of folded up her emotional tent and went home.”

Standard chemotherapy for advanced endometrial cancer in the late 1990s was an Adriamycin (doxorubicin)-based combination drug therapy. “It’s a very toxic, very hard chemo regimen, and it was even worse back then because we didn’t have all the anti-nausea drugs and other medicines we do now to help control the side effects,” says Lee.

Recent studies have shown that gentler regimens, such as Paraplatin (carboplatin) and Taxol (paclitaxel), are better tolerated and result in improved quality of life. “Today’s protocols are much less devastating for patients,” says Lee.

Shari Lewis holds her four-day-old daughter, Mallory, as they leave Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City in 1962. Mallory was the only child of Lewis and her husband, Jeremy Tarcher. Photo © Bettmann / CORBIS

Another major advance in treatment for endometrial cancer is the advent of minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery, which has become the standard of care for performing hysterectomies, says Gardner.

“Not having to open up the abdomen means much easier recoveries after hysterectomies,” she says. Surgeons also use sentinel lymph node biopsies—in which only the lymph nodes where cancer is likely to spread first are removed and biopsied—to diagnose and stage the cancer. “It’s a technique that allows us to zero in on the lymph nodes most likely to be affected instead of just taking everything,” says Gardner.

Lewis died in Cedars Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles on Aug. 2, 1998, less than two months after her uterine cancer diagnosis. Mallory was eight weeks pregnant at the time. “Just before she died, there was a moment where she pushed the oxygen tank away and looked at me and said, ‘I want you to know how much I love you and how happy I am about the baby,’ ” says Mallory.

Mallory spent the first year or so after her mother’s death accepting posthumous awards in her honor. At one event, she pulled out Lamb Chop, and the crowd went wild. “So we carry on the tradition,” says Mallory, who now travels around the country performing with Lamb Chop. “To this day, my mother, myself and my son, Jamie, are the only three people who have ever had their hand in Lamb Chop.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.