Editor’s Note: This story, written by Andrew Matthius, first appeared on Cancer Research Catalyst, the official blog of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). The AACR also publishes Cancer Today. You can read this and other stories on the AACR website.

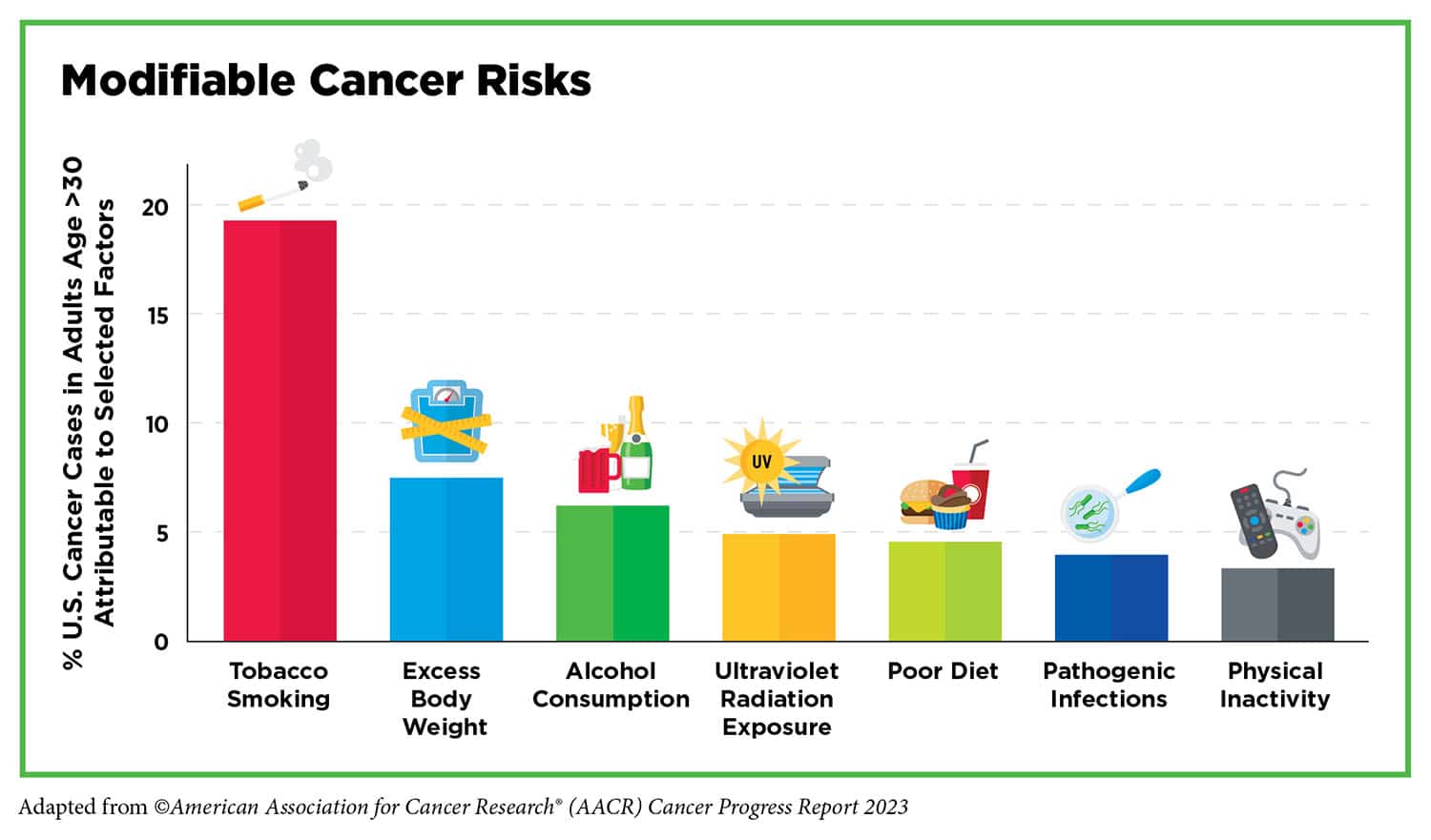

THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION estimates that 30% to 50% of all cancer cases are preventable.

Yes, much of that can be attributed to healthy lifestyle choices, including physical activity, better nutrition, lack of smoking, and light to moderate alcohol consumption, but knowledge can also be a powerful cancer prevention tool. According to the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Cancer Progress Report 2023, the United States experienced a 33% decline in overall cancer mortality between 1991 and 2020 largely thanks to public health campaigns and policy initiatives implemented to reduce smoking and increase early detection of cancers, based on study findings in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

As they say (or at least a series of public service announcements did in the ’90s), “The More You Know.” And in this case, the more you know about your cancer risks can be lifesaving, and what you don’t know can have negative consequences. A series of recent studies have found that some people may lack a certain level of clarity and/or awareness about some cancer prevention techniques such as screening and vaccination. This may cause gaps in ensuring benefit from available methods that can help detect cancer much earlier or outright prevent it.

Some Stool Samples Aren’t Fit To Be Tested

One of the several initial screening options for colorectal cancer (CRC) is a self-administered fecal immunochemical test (FIT) in which an individual provides a stool sample to be examined for hidden blood. The FIT is either administered at a health care office (often with verbal instructions) or via a mail-order program (with written and/or info-graphical instructions). But 1 in 10 FITs could not be processed due to unsatisfactory samples, according to results from a study published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, a journal of the AACR.

At least part of the issue is individuals don’t fully comprehend what is required to provide a sample that is deemed satisfactory for testing, according to Rasmi Nair, co-first author of the paper and an assistant professor at the Peter O’Donnell Jr. School of Public Health of UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. That was especially true for the mail-order program, which was 2.66 times more likely to produce unsatisfactory results.

Nair and her colleagues examined electronic health record (EHR) data of 56,980 individuals aged 50 to 74 who underwent FIT screening between 2010 and 2019 within the Dallas-based Parkland Health system. Parkland, which is considered a safety-net hospital, provides care to more than one million low-income, uninsured Dallas County residents. Overall, of the 10.2% FITs considered unsatisfactory, 51% were due to an inadequate specimen, 27% were attributed to incomplete labeling, 13% of the stool specimens were too old, and 8% had a broken or leaking container. Additionally, only 40.7% of individuals with unsatisfactory tests received follow-up FIT or colonoscopy screening within 15 months of the failed test.

Nair suggested that minimizing language and health literacy barriers could help, and the study authors pointed to visual instructions that showed positive results in improving sample collection in other studies. The authors also suggested that testing facilities include previously affixed patient labels or barcodes to minimize labeling errors as well as policy changes to allow using the sample ordering, mailing, or receiving date as the collection date—if the date is missing on the label itself and the sample is sent within the two-week widow. Finally, the authors also want to see a better system put in place to ensure proper follow-up.

“The fact that, in most instances, unsatisfactory FIT was not followed by a timely subsequent test highlights the need for systems to have a better, more comprehensive approach to tagging and following up unsatisfactory FIT,” said co-first author Po-Hong Liu, a gastroenterology fellow at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

The Need for More HPV Vaccine Awareness

The vaccine for human papillomavirus (HPV) has shown tremendous results in preventing cervical cancer. In fact, a recent study examining cervical cancer cases in Scotland found zero cases among women born between 1988-1996 who were fully vaccinated against HPV between the ages of 12 and 13, according to a paper published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The HPV vaccine, however, can benefit men and protect against other cancers as well, including anal, oral, and penile cancers. But this fact may not be properly presented to Hispanic and Latino men who identify as sexual minorities, according to results presented at the 16th AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved.

Between August 2021 and August 2022, Shannon M. Christy, assistant member in the Department of Health Outcomes and Behavior at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, and her colleagues surveyed individuals between the ages of 18 and 26 who were born male and were living in Florida and Puerto Rico, identified as Hispanic or Latino, had sex with a man or were attracted to men, and were able to read and understand Spanish. Among the 102 participants who said they had not received the HPV vaccine, 56% responded incorrectly or “do not know” to a question about whether most sexually active individuals are at risk for being infected with HPV; 20% responded incorrectly or “do not know” to a question assessing whether men can be infected with HPV; and more than half responded incorrectly or “do not know” to questions about the link between HPV and anal (54%), oral (61%), or penile (65%) cancers.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.