LYNETTE BONAR is Navajo but grew up in California and lived in Missouri after being stationed there in the military. Then, in 2003, she moved to the Navajo Nation.

Bonar, a nurse, took a job working for the Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation (TCRHCC), a nonprofit organization that provides health care in the western part of the Navajo Nation in Arizona. She soon realized there were substantial barriers to accessing care. Cancer patients were traveling to Flagstaff, Arizona, nearly 80 miles away, to get treatment. Bonar recalls asking, “Where is the cancer care? They’ve got to go that far? Are you kidding me?”

Today, Bonar is CEO of TCRHCC, and her organization recently opened the first cancer center within the boundaries of a Native American reservation. The new oncology and hematology clinic, called the Specialty Care Center, received its first patient on May 14, 2019, and began giving patients chemotherapy infusions in June 2019.

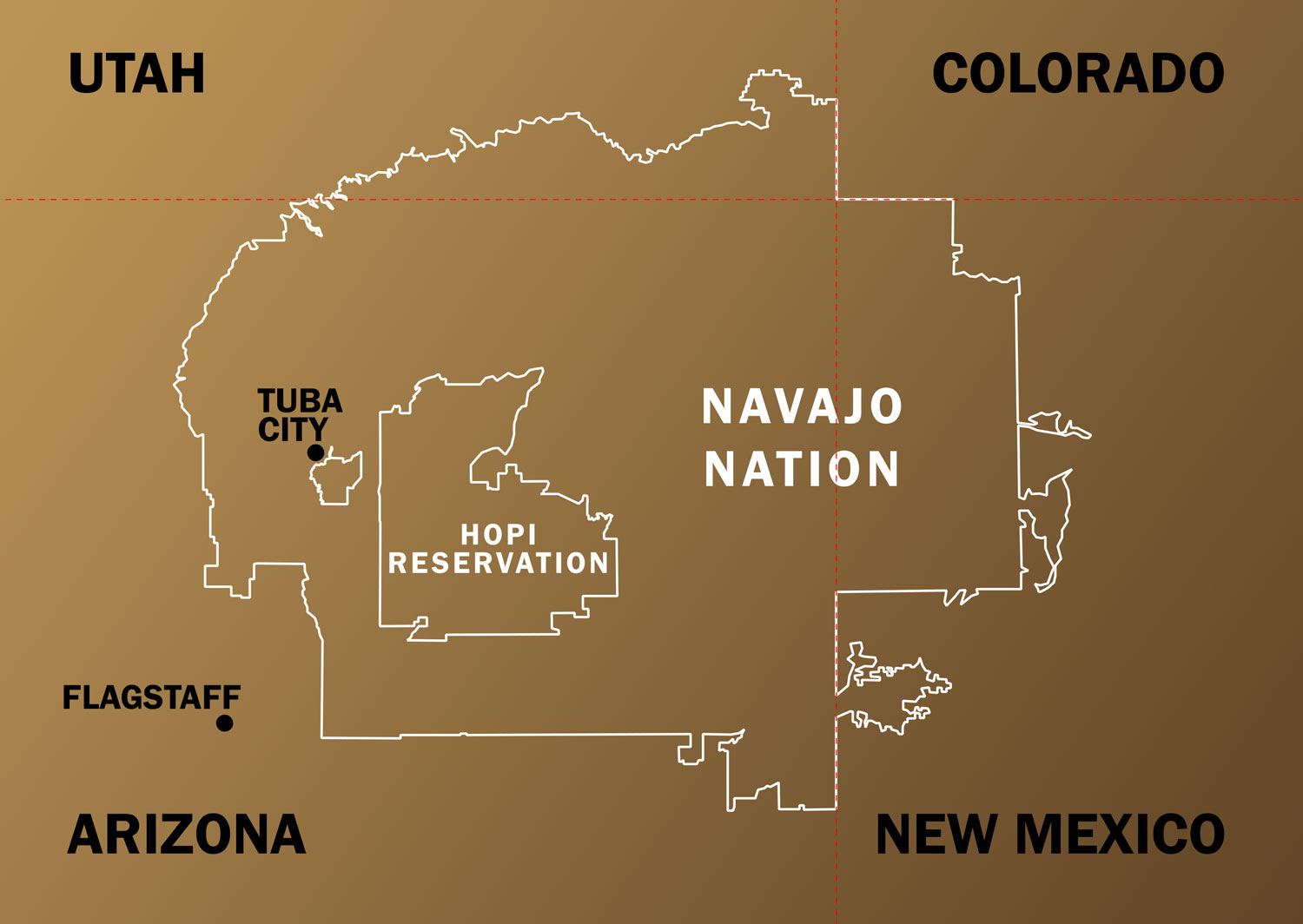

Tuba City, home to around 9,000 people, is in the Navajo Nation, about an hour’s drive east of the Grand Canyon, Bonar explains. The Navajo Nation stretches across parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah and is home to more than 170,000 people, mostly Navajo. The Hopi Reservation, which is surrounded by the Navajo Nation, is nearby.

The Navajo Nation is larger than West Virginia and stretches across parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. Image by Brad Jones

The hospital in Tuba City was originally built in 1975 as part of the Indian Health Service (IHS), a federal agency that provides health care to Native Americans. In 2002, TCRHCC formed as a nonprofit organization whose board of directors consists of members of local tribes. It receives funding from the IHS and is also supported by reimbursement for its services through health care payers like Medicare and Medicaid and by some grants and donations.

Bonar isn’t the only person who saw a need for cancer care in the Navajo Nation. Frank Dalichow started working in Tuba City in 2000 as a primary care physician. He noticed he was referring patients with cancer for care far away. Some patients who lived north of Tuba City were driving 150 miles to get to Flagstaff. “You can imagine how one must feel if you have to drive 150 miles one way and then drive back after having gotten chemotherapy, feeling sick, nauseous and weak and tired, and what kind of a burden that might be on not only the patient but their family,” Dalichow says.

Johanna Di Mento and Frank Dalichow are oncologists at the new cancer center in Tuba City, Arizona. Photos courtesy of Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation (TCRHCC)

His wife, Johanna Di Mento, meanwhile, was completing her training as a hematologist-oncologist in Tucson, Arizona. When her fellowship was done in 2005, she took a job at the oncology clinic in Flagstaff. Patients from the Navajo Nation were coming to Di Mento with highly advanced disease. “I saw so many cases like that,” she says. “It angered me. It was wrong.”

Patients would tell Di Mento that they didn’t want treatment because they were reluctant to burden their families with paying for gas and taking time off work to get to Flagstaff. “Often, it wasn’t even something they felt was an option for them because of the challenges and obstacles of even getting here,” Di Mento says.

Available statistics on cancer among Native Americans indicate that cancer incidence overall is lower than among white Americans. However, when Native Americans are diagnosed with cancer, they tend to have shorter survival than white cancer patients.

Dalichow decided to switch his specialty to hematology and oncology, hoping to eventually return to Tuba City to provide care there. Di Mento and Dalichow moved to Maryland in 2011 so that Dalichow could do an oncology and hematology fellowship. The pair stayed in touch with Bonar. When Bonar told them she was ready to open a cancer center in Tuba City, Dalichow and Di Mento volunteered to be the first oncologists. They moved back to Tuba City in January 2019.

At the new Specialty Care Center, staff provides treatment—including medical oncology appointments, chemotherapy and other infusions—to patients with common cancers. For now, patients still need to travel to receive radiation therapy, and patients with less common cancers need to get care at an academic medical center. The nearest academic center is in Phoenix, more than 220 miles away. Di Mento and Dalichow communicate closely with academic care providers and help their patients navigate the medical system.

“We hope to provide the oncology care that any American can expect to receive at a local oncology center, which we all here consider a basic human right,” says Dalichow.

Another benefit of offering cancer care in Tuba City is that Navajo language interpreters and an Office of Native and Spiritual Medicine are available, says Bonar. Being cared for in their own community will make it easier for patients to incorporate traditional practices into their care, like holding healing ceremonies, Bonar says.

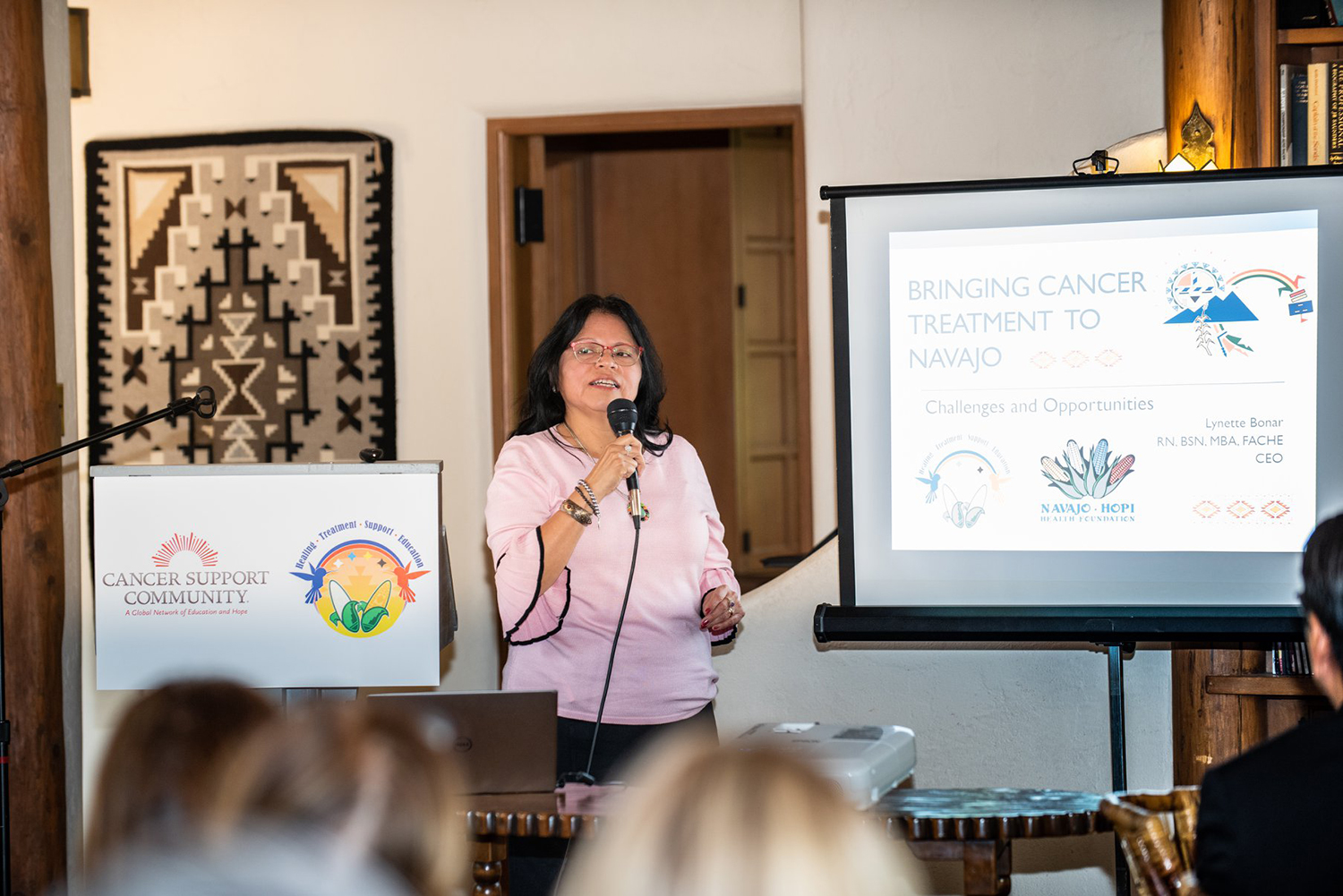

Lynette Bonar, CEO of Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation, speaks about the new Specialty Care Center. Photo by Ivan Martinez

The nonprofit organization Cancer Support Community (CSC), with support from the Barbara Bradley Baekgaard Family Foundation, is helping provide patients and their family members and loved ones with support, navigation and education at the House of Hope, located near the Specialty Care Center. A social worker who speaks Navajo is providing counseling and support services. CSC, with help from Bonar and her staff, has adapted its distress screening tool for use in Tuba City, recognizing that patients living in the area might have different sources of stress than patients at other CSC locations. For instance, the screening tool addresses worries about being able to complete chores like caring for livestock while undergoing treatment. “You’re dealing with a whole different set of barriers than we’re dealing with perhaps with underserved patients in Philadelphia or Washington, D.C., or Los Angeles,” says Kim Thiboldeaux, CEO of CSC.

Di Mento hopes that offering cancer care in Tuba City will ultimately lead to earlier-stage diagnoses. “I think the fact we’ll have a cancer center close to home will help people not be so afraid to investigate what’s going on in their bodies,” she says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.