NOT EVERY CHILDHOOD CONJURES UP happy memories. For Susan Keller and her three brothers, who grew up with an abusive mother and an alcoholic father who abandoned the family when Keller was 12, childhood was not so much a warm coming of age as a mad dash to escape.

“The thing about our growing up, it was so difficult. It was violent. It was traumatic. Everybody was just trying to keep their heads above water,” she recalls. Her youngest brother, Johnny, who she says suffered the brunt of his mother’s rage, left their family home in Los Angeles the day after he graduated from high school. Johnny chose an unconventional path, taking odd jobs, surfing California’s beaches, harvesting cannabis plants and psilocybin mushrooms, and raising and selling geckos.

Keller, who is seven years older than Johnny, lost contact with her brother when he was in his 20s—largely because their paths diverged so sharply. Keller married, had a daughter and ran her own speakers bureau for health care professionals.

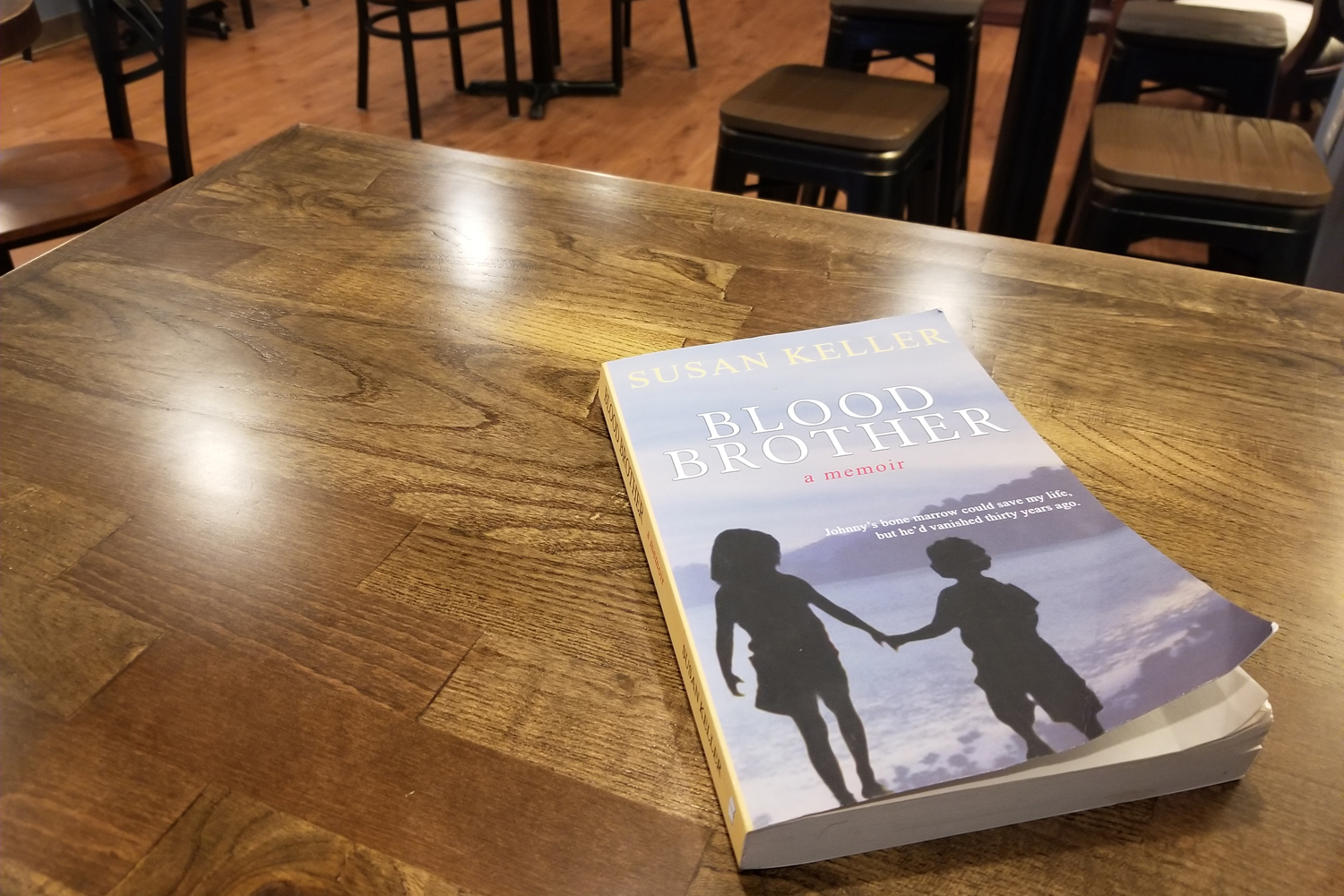

Through June 21, we will be discussing Blood Brother: A Memoir in our online book group.

In 2005, she was diagnosed with stage IV mantle cell lymphoma at age 55. After intensive chemotherapy, her cancer went into remission. But chances were good the cancer would come back unless she had a stem cell transplant. She had kept in contact with her other two brothers, neither of whom was a donor match. Her only hope was the brother she had not spoken to in 20 years.

In her memoir, Blood Brother, Keller writes about overcoming the trauma of her cancer treatment and moving forward after a dark time in her life. She ultimately tracked down Johnny, who held no ill feelings toward their parents. He ended up being a match and going through with the procedure. In telling their story, Keller exposes the twisted roots that give rise to family trees.

Keller, who has been in remission for 17 years, recently spoke with Cancer Today about her relationship with her brother, her motivation for writing the book and what she has learned about forgiveness.

CT: Do you think you would have ever seen your brother again if it weren’t for your cancer diagnosis?

KELLER: My brother and I may never have seen each other again. We talked a little bit when he was in his 20s and I was in my 30s. But he moved, and he did not give me his phone number or address. It wasn’t because he was angry or felt any negativity. It was just that he was ready to live his life, and he understood that he and I had very little in common. We still have very little in common, except an abiding gratitude that I have for him and he for me as well, as I still help him financially at times.

CT: There are chapters written from your brother’s point of view. Did he write them?

KELLER: I wrote the chapters from his point of view. Actually, one of my favorite chapters in the book is when he gets the call from me after he was out mushroom hunting. I wasn’t there when he received my call, but I saw his house later, so I knew the setting. I have seen him interact with his chickens, and I knew he had been out mushroom hunting that day. But I just kind of put my experience together with what he said he was doing at the time.

CT: Was it difficult to write this book, knowing you were also sharing painful or unpleasant details of your family members’ lives, especially your mother’s mistreatment of Johnny?

KELLER: Both of my parents were dead when I wrote the book, so that wasn’t a concern for me, but I was concerned about Johnny’s response because he had slipped into an underground life. I wanted to be respectful of him because the book highlighted him in ways that a lot of people might not have wanted to be profiled. He was extremely amenable to everything that I wrote, and he honestly had no changes. Had he said no, that would have put me in quite a quandary. I would have had to write another book.

CT: Did that openness surprise you?

KELLER: It is remarkable. He is a very spiritual guy. He’s into yoga and meditation and mushrooms, but he was so open to allowing me to share his story. He stunned me when he said he has no animosity toward our parents, and he was very sincere. He had no hesitation in getting tested to see if he was a match.

CT: You write about some conversations with your mother before she died and your struggle to make peace with your relationship, which seems more a point of conflict for you than for your brother. What role does forgiveness play in your story?

KELLER: I write in the book how forgiveness is a lifetime, not a moment. As a parent myself, I find it inconceivable to mistreat a child; however, both Johnny and I were abused. I’d like to say that I’ve reached a spiritual place of no blame, but that’s not quite true. I am, however, more open to the possibility that my parents’ lives were far more painful than I could understand as a child. If I could speak with them now, what I would say? Would I be kind? Would I be angry? Would I want anything to do with them? Forgiveness has many facets. But perhaps it is not up to me to judge. Perhaps that is misplaced hubris. This journey toward forgiveness is also a profound gift of my lymphoma.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.