WHEN DOUG OLSON LEARNED in 1996 at the age of 49 that he had chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), he remembers thinking he wasn’t going to make it. “Being told you have cancer is terrifying,” he says.

Olson was diagnosed with the most common type of CLL, which starts in the cells that become white blood cells called B lymphocytes. CLL can progress slowly, but eventually the abnormal B cells crowd out normal B cells. At first, Olson’s disease wasn’t aggressive or causing symptoms, so he went through a six-year period of watchful waiting without active treatment, while his blood counts were monitored to track his cancer.

In 2002, tests revealed that the cancer was progressing. Olson received a course of chemotherapy, which consisted of two infusions that sent his leukemia into remission. When his cancer came back in 2007, he was treated and went into remission again. But in 2009, he had another recurrence. This time, the CLL did not respond to chemotherapy.

Molecular analysis of the cancer cells showed his leukemia now carried a 17p deletion, an indication that the cells were missing a portion of chromosome 17 and the disease was expected to progress quickly. His doctors predicted that even the most aggressive chemotherapy would only buy him a little time.

Ellen T. Reich, whose multiple myeloma had stopped responding to other treatment options, shares her experiences receiving CAR T-cell therapy as part of a clinical trial. Read more.

“Without a bone marrow transplant, basically I could expect to survive maybe another year or two,” says Olson. He also knew a bone marrow transplant, which is commonly referred to as a stem cell transplant, would be grueling. First, he would have to endure aggressive chemotherapy to knock out blood-forming stem cells in his bone marrow. Then, he would receive a donor’s stem cells. After the procedure, he would need to see how the newly transplanted stem cells would graft in his body. It was possible the cells would recognize Olson’s body as foreign, causing a condition known as graft-versus-host disease that occurs when donated immune cells attack the body’s cells. Olson also worried that he would be out of options if the treatment didn’t work. Additionally, Olson’s four siblings were screened to see if they might be able to donate their stem cells to their brother, but, against the odds, none was a suitable match.

That’s when Olson’s doctor, David L. Porter, a hematologist-oncologist at Penn Medicine’s Abramson Cancer Center in Philadelphia, told him that they had just opened a clinical trial testing a new type of “living drug” called CAR T-cell therapy, short for chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy.

“They would use my [own] white cells—after they were modified to recognize the cancer—to attack the cancer,” Olson says.

Olson liked the idea of trying something new. More importantly, he says, “it looked [to me] like it could work.” Soon after Porter brought up the study, Olson enrolled in the trial. He was the second patient in the study to receive the experimental treatment.

A ‘Revolutionary’ Approach

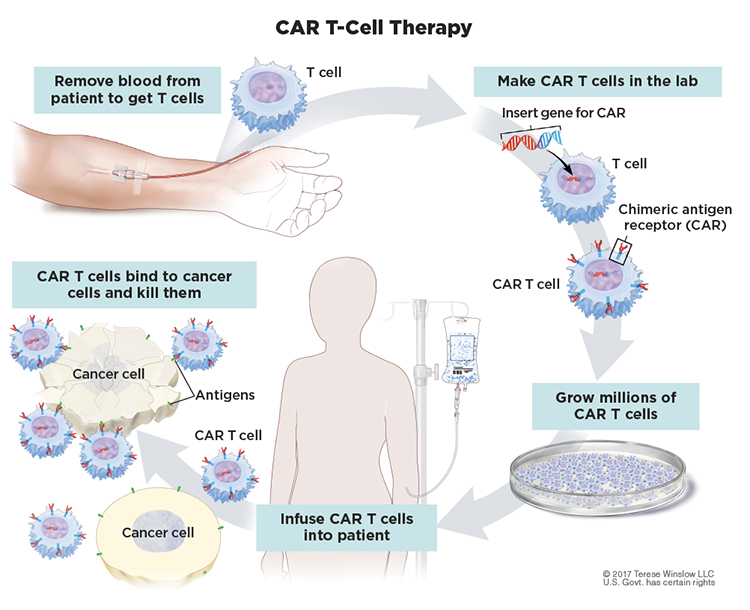

T cells are white blood cells that protect the body from threats, such as viruses and other attacks, that they recognize as foreign to the body. In CAR T-cell therapy, the cells are engineered to better recognize and kill cancer cells. Doctors first collect a person’s T cells from the bloodstream. Next, the cells are sent off to a lab for modification with a special receptor, known as a chimeric antigen receptor, that equips these modified cells to recognize a specific target. For B-cell malignancies including CLL, the modified T cells target CD19, a protein found on abnormal B cells. The modified cells are then grown in the lab by the millions before they are infused into the patient. The goal is for the modified T cells to keep multiplying in the body and get rid of the cancer by eliminating abnormal B cells. In the process, the treatment can also destroy healthy cells since healthy B cells also have CD19 proteins. (One reason this treatment approach can work more readily in B-cell cancers compared to other cancer types is that a person can live without B cells.)

Now, CAR T-cell therapy is no longer experimental. It has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat many types of blood cancers, including lymphomas, some leukemias and multiple myeloma. The first CAR T-cell therapy became available in August 2017 when the FDA approved Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) for patients up to age 25 who had B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) that did not respond to or had relapsed after other treatment.

Kymriah’s approval was based on a trial in 63 people whose cancer had progressed following prior therapies, including a stem cell transplant in about half of the cases. Most patients who received the CAR T-cell therapy experienced adverse reactions—including infections, bleeding episodes, kidney injury, delirium and an acute inflammatory condition known as cytokine release syndrome—as their revamped immune systems aggressively attacked both cancerous and healthy B cells. But the data also showed a remission rate of more than 80%, with more than 60% achieving complete remission, meaning tests couldn’t detect any cancer cells, in a group of people who otherwise had no more treatment options.

In October 2017, the FDA approved a CAR T-cell therapy called Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) to treat adults with certain types of large B-cell lymphoma that had relapsed or hadn’t responded to at least two other therapies. The clinical trial leading to the approval included 100 adults with this type of cancer—half of whom achieved complete remission.

Six CAR T-cell therapies are now commercially available for several blood-related cancers, including two recent additions for people with multiple myeloma. While the success rate for CAR T-cell therapy varies for each of these cancer types, Porter, who is now Penn Medicine’s director of cell therapy and transplantation, notes that the “dramatically successful” and “revolutionary” treatment has been tested and subsequently used in people for whom there were few, if any, other options. “Even benefiting a small number of patients would be dramatic [in this context], but this has benefited a large number of patients,” he says. “It has transformed the way we treat people.”

Taking a Longer Look

Despite these successes, patients who receive CAR T-cell therapy often relapse. For example, a study in the May 20, 2021, Journal of Clinical Oncology looked at long-term outcomes for 50 children and young adults treated with CAR T-cell therapy for relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL after five years. About 60% of patients achieved complete remission. More than half of those who achieved complete remission following CAR T-cell therapy eventually needed a stem cell transplant, and less than 10% of these patients had a subsequent relapse. This shows that additional treatment often is necessary.

The success of CAR T-cell therapy in lymphomas and multiple myeloma has generally been more modest than in ALL, although researchers are awaiting long-term data. The first approval for CAR T-cell therapy to treat multiple myeloma came in 2021 and is for people with myeloma who have not responded to or relapsed after four or more lines of therapy. The approval was based on evidence showing that 72% of the 127 patients in the trial had cancer that responded partially or completely to the treatment—with 28% having a complete disappearance of all signs of multiple myeloma. Sixty-five percent of those who achieved a complete response did so for at least 12 months.

These outcomes after the cancer hasn’t responded to other therapies have prompted some to wonder what might happen if the treatment were offered earlier. “It begs the question, if CAR T cells are good, is there any value of treating this way up front instead of chemo?” says Renier Brentjens, an immunologist and oncologist at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, who helped develop the CAR T-cell therapy approach. “In patients with tumors with qualities we think won’t respond well to standard chemotherapy, perhaps we could move [CAR T-cell therapy] closer to the forefront.” But there remain uncertainties about long-term benefit compared with established first-line treatments, and another major challenge for all CAR T-cell therapies is cost. The list price for a single infusion of Abecma (idecabtagene vicleucel), the first CAR T-cell therapy approved for myeloma, was nearly $420,000 in 2021. Kymriah is even more, with a cost of $475,000.

Moving Toward the Front Line

Physicians often start children who have ALL with CAR T-cell therapy as soon as there are signs that standard treatment isn’t working, says Michael Verneris, a hematologist-oncologist and director of bone marrow transplantation and cellular therapy at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora. He notes that the FDA label for CAR T-cell therapies in ALL includes children and young adults who either have a second relapse or have leukemia that doesn’t respond to chemotherapy. It’s clear when a child relapses, but a poor response is more loosely defined, leaving some room for judgment by experienced clinicians, Verneris says.

He explains that doctors know from the outset that some children, including kids with Down syndrome who also are at higher risk for ALL and the youngest infants, don’t do well with aggressive chemotherapy. In the case of infants with ALL especially, he and his team have begun meeting with parents early in the disease course to discuss the possibility of CAR T-cell therapy.

“Sometimes we’ll collect and freeze [T] cells with the idea that then they’ll be available when we need them,” Verneris says.

There’s an additional benefit of banking these cells early. Experts hypothesize that the immune system isn’t as healthy in a person who has already undergone months or years of chemotherapy. By collecting T cells prior to the start of chemo, people have the option to bank potentially healthier immune cells that might produce healthier CAR T cells down the line.

The cancers for which CAR T-cell therapy has been approved or is being studied.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved six CAR T-cell therapies. The treatment is an option for people with the following relapsed or refractory B-cell cancers:

- Acute B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia

- B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Follicular lymphoma

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Multiple myeloma

Trials are also ongoing for CAR T-cell therapy in many other cancers, including some solid-tumor cancers:

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Acute myeloid leukemia

- Glioblastoma

- Gliomas

- Colorectal cancer

- Ovarian cancer

- Pancreatic cancer

- Lung cancer

Verneris believes treatment protocols will move toward offering CAR T-cell therapy earlier, perhaps even in the front line, for patients predicted to fare poorly with standard chemotherapy. He notes that CAR T-cell therapy offers people with ALL a greater than 85% chance of remission after a single difficult month of treatment. After one year, about 45% of those who have had CAR T-cell therapy are alive and disease-free, Verneris says. By comparison, chemotherapy offers an 80% to 90% chance of reaching complete remission in ALL, but it also takes much longer, often years, with more damaging effects on the body. Further, about half of the patients who achieve remission after chemotherapy will relapse, according to the American Cancer Society. Verneris says he believes using CAR T-cell therapy could shorten the overall treatment duration for these patients and reduce long-term toxicity associated with chemotherapy.

Clinical trials have also looked at combining a single round of chemotherapy with CAR T-cell therapy with varying results. Two clinical trials in people with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) who received CAR T-cell therapy after one round of chemotherapy showed people lived longer without their cancer progressing compared with those who received several rounds of chemotherapy followed by a stem cell transplant. However, a third trial didn’t find a difference in the time it took for the cancer to progress in patients using either approach. The trials each tested a different approved CAR T-cell therapy for NHL: Yescarta, Breyanzi (lisocabtagene maraleucel) and Kymriah, which might explain the differences in outcomes. The findings still suggest that people may benefit from having CAR T-cell therapy in place of a stem cell transplant. Verneris says that some physicians already lean toward using CAR T-cell therapy over stem cell transplant for children with ALL, given that CAR T-cell therapy takes less time and is less toxic. He notes that children have about a 10% chance of dying in the first year with a transplant. While CAR T-cell therapy also can have life-threatening side effects, he says that experienced doctors have learned how to manage its side effects to make the procedure much less risky.

“I suspect over the next 10 years, we’ll see [CAR T-cell therapy] progressively move forward,” Verneris says. “We have an obligation to do it in a logical, staged manner. But I expect it will continue to move up. It really is highly effective and much less toxic than other therapies.”

‘Over the Moon’

Olson’s experimental CAR T-cell infusion in 2010 landed him in the hospital after three weeks with symptoms he describes as feeling like a bad flu. At the hospital, he learned he had tumor lysis syndrome, a life-threatening condition that occurs when cancer cells break down and flood the bloodstream, which overtaxed his kidneys. The side effects from CAR T-cell therapy are caused in large part by the battle between CAR T cells and B cells. Olson remembers feeling excited when his symptoms began, because it meant that his immune system was launching a response. While Olson was in the hospital, Porter told him 18% of his white cells were CAR T cells and Olson was “over the moon.” His CAR T cells were not only killing off cancerous B cells, but they were also multiplying. Soon after getting the good news, Olson was discharged from the hospital. Five weeks after his CAR T-cell therapy infusion, Porter told Olson they couldn’t find any cancer in his bone marrow or blood.

Olson is not alone in his treatment response. A Feb. 2, 2022, study in Nature described how Olson and another patient, Bill Ludwig, who was the first patient in that same trial, were still in remission after a decade. All these years later, both still had detectable CAR T cells in their bodies. Ironically, CAR T-cell therapy isn’t yet approved for CLL, although studies are ongoing. In part that’s because of successes in other targeted treatments for CLL and lingering questions about the durability of remissions following CAR T-cell therapy.

Olson, who volunteers with the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s First Connection Program, sometimes talks to people who are thinking about receiving CAR T-cell therapy to treat their lymphoma. He likes to remind them that while CAR T-cell therapy has risks, patients have been receiving the cell therapy for more than a decade, giving doctors more experience in managing the side effects. CAR T-cell therapy, he tells them, “is no longer experimental.”

“There’s a lot to learn, but the pace of discovery has really been quite rapid,” Olson says. “Compared to where things were 10 years ago, it’s pretty amazing.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.