AFTER SPENDING THE EVENING courtside covering a University of Texas versus Baylor University men’s basketball game on Feb. 1, 2016, ESPN reporter Holly Rowe caught a late flight from Dallas to Salt Lake City, where she lived. The next morning, she would undergo surgery to remove a tumor from under her armpit. The surgeon would also remove 29 lymph nodes.

This would be the veteran reporter’s second cancer surgery. In May 2015, Rowe had been diagnosed with desmoplastic melanoma, a rare, fast-spreading form of skin cancer, after she noticed that a red scar from a previously biopsied mole on her chest kept getting larger. Only her close friends, family members and boss knew about the first surgery to remove the tumor. This time would be different. ESPN asked Rowe to prepare a statement, and the cable sports network issued an announcement.

After the surgery and still woozy from anesthesia, Rowe thought she was imagining things when her name and news of her health status scrolled across the bottom of the TV screen as she watched a college basketball game from her hospital bed. “It all seemed so strange. I was used to reporting the news, not being the news,” she says. Since that day, Rowe, 53, has often confronted her disease in the public eye. Throughout treatment, the veteran reporter continued to offer sideline analysis and conduct interviews with coaches and athletes for ESPN. She also openly shared the ups and downs of her treatment, receiving support from many fans and inspiring others with cancer along the way.

Staying on the Job

Melanomas are a group of cancers that form in the melanocytes—cells beneath the skin’s surface that produce melanin, the pigment responsible for skin color. Most melanomas are linked to skin damage from the sun’s ultraviolet rays. Melanomas are more likely to occur in light-skinned people, though they are diagnosed in people of all skin colors.

It is estimated that more than 96,000 people in the U.S. will be diagnosed with melanoma in 2019, accounting for just 1% of all skin cancers. However, melanoma is responsible for most skin cancer-related deaths and is expected to cause more than 7,200 deaths this year. Desmoplastic melanoma is rare, accounting for less than 4% of melanoma diagnoses. This type of cancer forms deep-infiltrating, fibrous tumors that can be difficult to remove and don’t typically respond to chemotherapy or radiation. In addition, desmoplastic melanoma frequently recurs.

Rowe didn’t want to think about this possibility, so the self-described “workaholic” kept covering college sports. “I thought if maybe I could keep working, it would mean I wasn’t sick,” she recalls. The second surgery left a 15-inch scar. Yet on Feb. 29, 2016, less than a month after the surgery, she was back on the court. In March, she covered the men’s and women’s NCAA college basketball championships with plastic tubes stitched into her incision to drain fluid into a bag under her blouse.

Through parts of April and May, Rowe underwent treatment with high-dose interferon to reduce the risk of the cancer coming back. Five days a week for four weeks, she went to the Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City to receive the infusion. The side effects were “horrific,” she says. “I was deathly ill. I couldn’t eat. I could barely walk. I would lie in bed all day and then get up and go to work.”

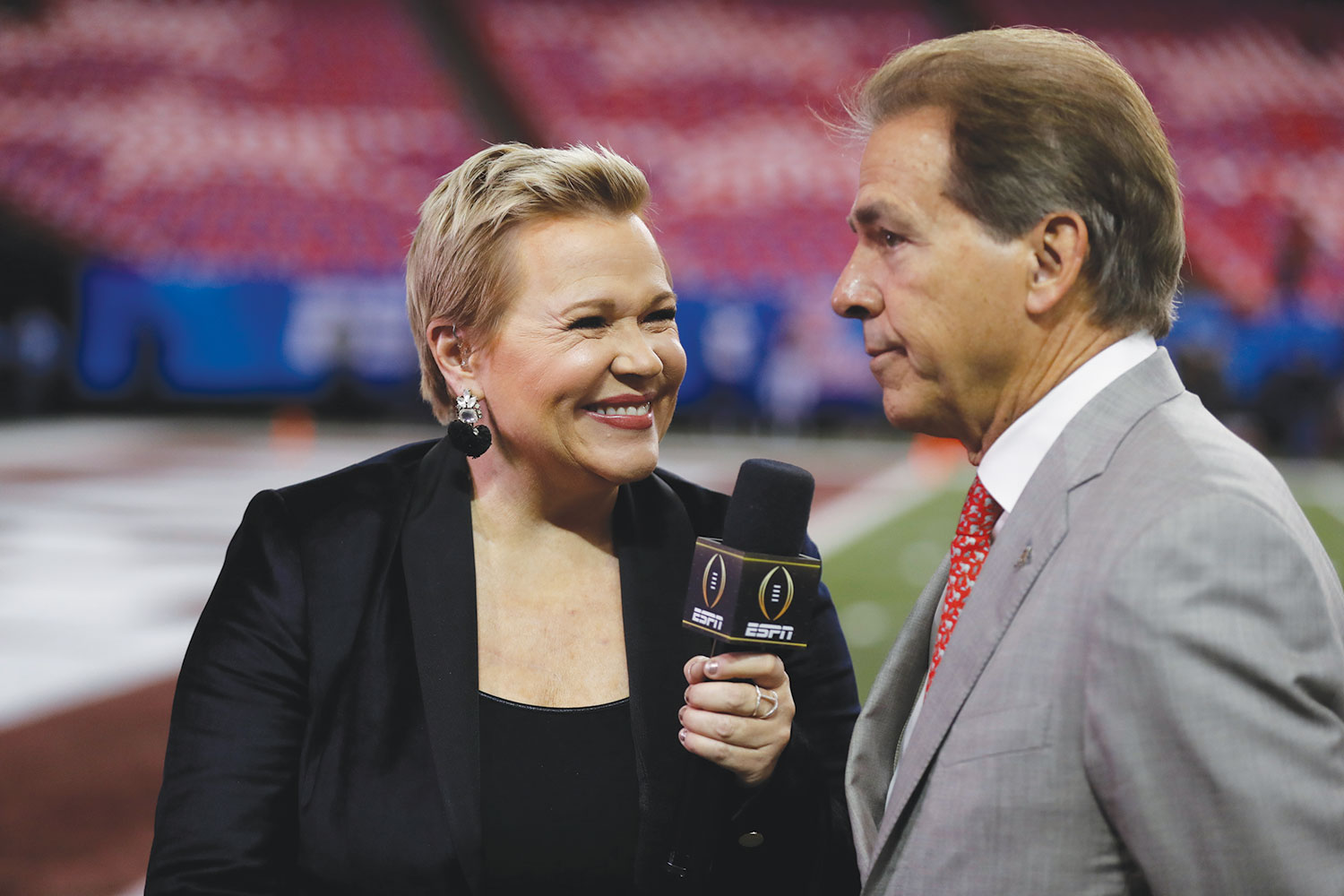

Holly Rowe interviews Nick Saban, head coach of the University of Alabama football team, during a college playoff game against the University of Washington. The game was played in the Georgia Dome in Atlanta on Dec. 31, 2016, a few days after Rowe received an immunotherapy treatment. Photo by Kent Gidley / Crimson Tide Photos

Doing the job she loved was “powerful” medicine, says Rowe, who has been obsessed with sports for as long as she can remember. “I think athletes are some of the most fascinating people in the world,” she says. While undergoing treatment, she covered games of the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) and the Women’s College World Series. “Every day, I’d see people winning. I would see these women doing amazing things. That really inspired me and gave me amazing strength,” says Rowe.

By opening up about her treatment struggles on TV and via social media, Rowe inspired others. That summer, her long blond hair began falling out—an unusual side effect of interferon treatment. After breaking down in tears one morning when she saw large clumps of hair on her pillowcase, she decided to have her head shaved. She documented the moment by sharing a video of the event on Facebook.

In response, hundreds of people posted messages of support to Rowe on Facebook and Twitter. Later, at a college basketball game, Rowe met a teenage girl with cancer who decided to go to school without a wig after seeing Rowe without one. And a female basketball referee thanked Rowe for giving her the courage to officiate games bald after struggling to find a wig that would stay put as she moved around the court.

In addition to hair loss, Rowe developed lymphedema, a painful and persistent swelling caused by the buildup of lymphatic fluid that can occur after lymph node removal surgery. Air travel exacerbated the condition. Since Rowe had to fly to most games, she often was seen on TV wearing a compression sleeve to help reduce pain and swelling. “Many women, especially breast cancer survivors, thanked me for making it seem like a normal thing,” she says.

Living Well

Just five months after her second surgery, Rowe got devastating news. A scan in July 2016 showed three masses in her right lung; a biopsy confirmed the tumors were cancer. “The doctor told me I needed to start thinking about how I wanted to spend my time,” says Rowe, who didn’t publicly share the news until months later.

Throughout her previous treatments, Rowe thought about her mortality. “There was this underlying tension and fear in my spirit, and it was keeping me from living well,” says Rowe. She drew strength from a turning point she experienced while struggling with the side effects of interferon. While covering a WNBA game from Madison Square Garden in New York City, she turned her attention to a children’s choir singing the national anthem. “It just brought me so much joy. In that moment, I felt truly happy,” remembers Rowe. She jotted down the experience so she could remember it, then started keeping a journal filled with other “joyful moments.” These moments continued to carry her through each day, even after she learned that the cancer had returned.

“In a weird way, I began to feel almost grateful for the cancer because it forced me to be so much more intentional about living,” says Rowe, who started playing the piano again and formed a band with friends. In the fall of 2016, she moved to New York City to be closer to her son, McKylin Rowe, who is now 24. McKylin, an actor, welcomed more quality time with his mom. “I was all for it, especially since I didn’t know how much more time we would have,” he says. The two moved into a sunny apartment that has a quiet garden and is a block away from Central Park in Manhattan. They spend the few days when Rowe isn’t traveling watching movies together.

Holly Rowe and her son, McKylin, pose for a selfie in New York City’s Central Park. They share an apartment nearby. When Rowe is not covering sports, she enjoys spending time with McKylin. Photo by Michael Weschler

Rowe’s love of sports didn’t rub off on McKylin—he’s a movie buff—but the mother and son bond over sports movies. One afternoon, the pair watched Creed, the seventh installment in the Rocky film series. In the movie, the fictional boxer Rocky Balboa—many years older than during his prime in the 1970s—copes not only with his legacy as he coaches a young fighter, but also with his own mortality when he finds out he has cancer. “We sobbed our eyes out. That movie resonated with us so much,” says McKylin.

Just as the fictional boxer overcame challenges, Rowe kept moving. “I thought if I could just keep running, I could survive,” she says.

A New Approach

Shortly after finding out that the cancer had spread to her lung, Rowe learned about research on desmoplastic melanoma at UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center in Los Angeles through a connection at the V Foundation for Cancer Research, a nonprofit affiliated with ESPN. She enrolled in a clinical trial testing a combination immunotherapy approach. Participants took the drug Keytruda (pembrolizumab) with another immunotherapy drug or with a placebo. (The trial ultimately showed the combination was no better than Keytruda alone.)

From August 2016 through August 2018, Rowe flew to Los Angeles every 21 days for intravenous infusions. Within three months, the tumors in her lung had started to shrink. By the end of treatment, the largest tumor had decreased in diameter from 21 millimeters to 3 millimeters. Her doctors told her the remaining mass was likely residual scar tissue.

Holly Rowe focuses on finding joyful moments in everyday life. Here, she relaxes in her New York City apartment. Photo by Michael Weschler

In the past, desmoplastic melanoma was considered difficult to treat, says Antoni Ribas, Rowe’s medical oncologist and an investigator for her clinical trial at UCLA. “If the cancer had spread to the lungs [as it had in Rowe’s case], it was nearly always a fatal condition,” Ribas says. “It was very frustrating. This cancer didn’t respond well to any systemic therapy we had.”

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, which block mechanisms that allow cancer to evade the immune system, have changed the outlook. “These drugs have dramatically altered the way we treat some cancers. Holly is an example of that,” Ribas says.

Research has shown that some immune checkpoint inhibitors approved for advanced melanoma are especially effective in treating this rare subtype. In fact, Ribas and colleagues published research on Jan. 18, 2018, in Nature that showed 70% of 60 patients with advanced desmoplastic melanoma responded to immunotherapy, specifically PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. In addition, 74% of those patients who responded to the immunotherapy were alive after almost two years. Patients who previously didn’t have this option would have typically lived for only six to nine months, Ribas says.

During most of Rowe’s two years of receiving immunotherapy, she says she was “able to function at a pretty high level,” though she did experience a few uncomfortable side effects such as itching. “It sounds kind of dumb, but I kept an oyster fork in my purse and used it to scratch myself. I took it with me everywhere I went,” Rowe says. She also experienced significant pain in her feet. Covering college football became a real struggle. “I walk about 6 miles during each game, and by the end, I’d just be limping off the field, not sure how much longer I could do this. That really scared me,” she says.

Moving On

Rowe now has follow-up visits and scans at UCLA every three months. She still deals with lymphedema from her second surgery as well as joint pain. “I wouldn’t say I’m back to normal yet, but I’m feeling better and better,” she says.

While initially hesitant to share her personal struggles with sports fans, Rowe is glad she went public with her diagnosis and treatment. “If me going through the hard stuff publicly helped someone else have a better day, I think that’s important,” she says.

To help others, Rowe continues to work with several patient advocacy groups, including AIM at Melanoma, the V Foundation and the Melanoma Research Foundation. She admits she never thought about skin damage when she used tanning beds or got blistering sunburns. “We need to be shouting from the rooftops that these habits are literally killing us,” says Rowe.

While she provides insights about athletes on the court, Rowe’s grit and ambition to live a “big life” despite cancer have won her a cheering section all her own. One of her biggest supporters is her son, who says his mother is his hero. “She did what she wanted no matter what the cancer took from her. My mom is the true Rocky,” McKylin says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.